In 1929, 60% of all families had annual incomes of $2,000 or less; 42% had annual incomes of less than $1,500. More efficient machines had made it possible for the productivity of industrial workers to increase by 32% during the 1920s, but their wages had increased only 10%. Profits from the industrial corporations grew 62% and went largely to the wealthiest 5%.

| Year | Richest 5% | Richest 1% |

| 1923 | 22.9 | 12.3 |

| 1929 | 26.1 | 14.5 |

The slump in automobile sales was paralleled by the decline in the construction of new housing, causing unemployment in the building trades. Fewer suburban houses meant fewer markets for appliances, wall coverings, and other activities related to home building.

The economy was in trouble but people, dazzled by a surging stock market, ignored it. Agriculture was in a depression as farmers sold in a competitive market while having to buy in a protective market because US business subverted free enterprise by having the government tax foreign manufactured goods high enough to guarantee sales to US producers. Improvements in farm technology, which allowed farmers to produce more, only made the situation worse for demand was inelastic. The consumer economy was slowing as incomes skewed to the rich. In 1929, the richest 10% of families received 39% of disposal personal income while the bottom 10% only got 2%.

People seemed to be forgetting that capitalism needs to expand, that demand for housing, clothes, automobiles, stoves, and many other consumer goods generates demand in other sectors of the economy. But mass production necessitates mass consumption. Mass consumption necessitates an income distribution that allows consumers to buy. Without the appropriate income distribution, warehouses will burst at their seams and production lines will clog. Ethnic discrimination usually meant lower pay for the affected groups. The coal industry was in economic trouble as US consumers and businesses switched more and more to petroleum or hydroelectric sources of power. The introduction of synthetic fibers, such as nylon, dealt body blows to the cotton and wool textile industries. The wealthy bought luxuries but could not buy enough to sustain the consumer economy.

Many of the wealthy, as well as others, joined the speculative stock market sending stock prices to greater and greater without regard to company performance; In October, 1929, the bubble burst. The crash meant the tremendous loss of capital as prices declined $74 billion from 1929 to 1932 and the repatriation of much of US investment abroad. The Germany economy collapsed followed by the British and french economies. Germany could not pay the reparations it owed to the victors of WWI or make debt payments to US lenders, setting off a chain reaction. The world entered an economic depression.

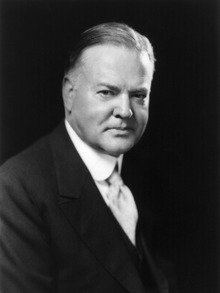

President Herbert Hoover did not know how to meet this crisis. His government began buying farm surpluses in order to prop up prices but it did not buy enough to make a difference. The Farm Board loaned money to farmers to establish cooperatives (a socialist measure) but the millions of farmers scattered across millions of miles had difficulty in cooperating. Farm income went from $8 billion in 1929 to $3 billion in 1993, a decline of 62.5%.

Republican wisdom said that high tariffs were good for the economy and, besides, in a time of world crisis countries tend to become very nationalistic, so the Congress passed, with Hoover's acquiescence, the very high Hawley-Smoot Tariff in 1930. Raising the tariff made things worse because it meant that foreigners could sell less in the US and thus earn fewer US dollars with which to buy US goods or make payments on debts owed to US citizens. Exports fell 50%.

As historians Peter N. Carroll and David W. Noble note, Hoover feared that the collapse of the large corporations would bring down the entire US capitalist system. After all, one percent of the banks held 50% of banking assets. Three corporations—Ford, Chrysler, General Motors—manufactured 85% of the automobiles sold in the US. Chain stores dominated retail sales and their difficulties had national repercussions.

Business and industry met the crisis as they had always done—they cut production, lowered wages, reduced working hours, and fired workers. Unemployment rose from 1.5 million in 1929 to 13 million in 1933, a figure which represented 25% of the labor force. Even such a high percentage hid the dimensions of the problem because it did not what percentage had been forced the part-time work. Industrial wages fell from $25 a week to $17 a week, a decline of 32%. By 1932, sawmill workers were only earning five to ten cents an hour; Tennessee female mill workers earned $2.39 for 50 hours work; and Connecticut women got between 60 cents to a dollar for a 55 hour week. To help the situation, the Hoover administration sept close to a billion dollars in public works programs but he would not go further. Nor would he argue for direct relief to the unemployed and starving because he feared that doing so would corrupt them. Although he had administered relief progress in Europe after the First World War, he saw that as only an emergency measure caused by war. He believed that doing a similar thing in the the US would become a permanent practice. To many, he was callous. As people lost their homes and created shanty towns, they derisively called the "Hoovervilles." Hoover argued that private charities and state and local governments should be the institutions to provide relief. But they were suffering as well and could not deal with a problem of this magnitude.

Hoover and the Republicans saw aid to corporations as being different. Whereas they believed that helping the individual citizen weather the Depression would corrupt him or her, aiding corporations and other business was different. To many, it appeared that the Republicans were only interested in the rich. The newly-created Reconstruction Finance Corporation aided only the large corporations.

Hoover broke precedent because the national government assumed some responsibility for what happens during an economic depression but he was not willing to go far enough. He believed that the depression was part of the normal business cycle and had been caused by international factors and not US ones. to him, "prosperity was just around the corner." The best thing for the country to do would be to wait the crisis out.

by Donald J. Mabry