From Robert J. Shafer and Donald J. Mabry, Neighbors—Mexico and the United States: Wetbacks and Oil. (Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1981), 28-31. With hypertext additions.

With the acquisition of Louisiana, Spain again decided it could let eastern Texas decay. This decision was not altered much when Napoleon demanded Louisiana back in 1800 and then sold it to the United States in 1803. Texas in 1820 had only four thousand Mexican settlers, and Mexico for many miles south of the Río Grande was not much more populated. Mexicans did not go voluntarily to Texas, because central Mexico seemed more valuable and assisted emigration was too expensive in view of Spain's other defense needs. So Texas lay virtually unpeopled when U.S. citizens, led by Stephen Austin, were allowed by the newly independent government of Mexico to settle in the early 1820s.(1)

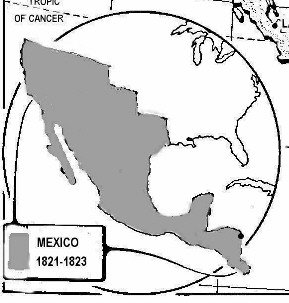

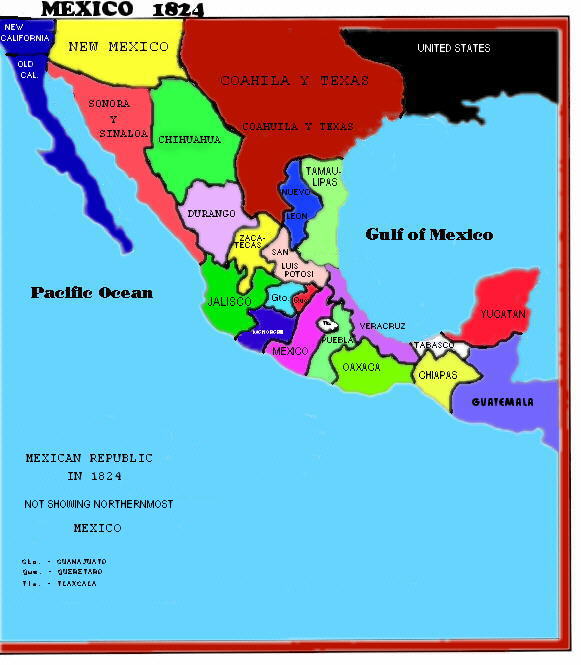

Texas was but part of the huge paper tiger Mexico inherited from Spain upon declaring its independence in 1821. Few Europeans lived in the enormous territory from Texas north and west below the boundary of the purchase Jefferson made from Napoleon. But in the United States, nearly forty years old in 1821, people were pouring to the west who were not much impressed by paper tigers.

Americans had been moving across the Mississippi since the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Louisiana became a state in 1812, Missouri in 1821, and clearly other western states would follow. Frontiersmen, traders, and adventurers prowled the Louisiana-Texas border between Natchitoches, a constant threat to peace between Spain and the United States. Most settlers on the Austin lands in Mexican Texas came from southern states, and counted on using black slaves. Most were Protestants. They resisted adoption of the Spanish-Mexican language, religion, and law, justifying the fears of those Mexicans who opposed this method of providing population and revenue in a lightly held land.

Events in the United States continued arouse these Mexican fears. In 1822 a hide trade by sea began between New England and Mexican Upper California. In 1825 the U.S. Congress authorized a commission to lay out a rail from St. Louis to Mexican Santa Fe, where the population was still small, poor, and isolated.

In the 1820s in the United States there was talk that the boundary with Mexico was not at the Sabine River as specified in the treaty of 1821 with Spain, but farther south at another other stream, even the distant Río Grande. Also worrisome to Mexico was an alteration in the relative strengths of the nations. In 1790 the population of Mexico was 5 million, that of the United States 4 million; but in 1830 it was respectively, 6 million to 13 million.

During the years 1826 and 1827, a few of the new settlers in Texas rose in arms to create the Fredonian Republic; although it was put down by Americans from the Austin grants, it increased alarm in Mexico City. The latter tried and failed to persuade Mexicans to move to Texas. Then in 1829 Mexico abolished slavery for all the country but found it could not enforce it in Texas. By that time there were 25,000 Americans living in the province, so in 1830 Mexico combined Texas with the state of Coahuila, with its capital at Saltillo, more than six hundred miles from northeastern Texas. Texans objected to that. Then in 1835 Mexicans decided to replace their federal system with a centralized republic--not just because of the Texas issue--and Texans believed the new system interfered with their rights. The result of accumulated fears and resentments was a rebellion in Texas and a declaration of independence in 1836.

Mexico was too weak to subdue Texas. Furthermore, urged by England and France, it became almost reconciled to the idea of an independent Texas, as a buffer against the United States. The European powers dreamed of Texas as a state reaching from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific, permanently restricting Yankee power. That dream was shattered by Texas preference for incorporation into the U.S.

After ten years of argument over the issue of admitting new slave territory, in 1845 Texas was taken into the Union. The ensuing war with Mexico might have been avoided if the only issue had been Texas, but Americans were moving in on Mexican claims west and northwest of there, too: traders with New Mexico; fur gatherers in the Rockies; settlers and adventurers in California; and, in the arrival of Brigham Young and his Mormon followers at the basin of the Great Salt Lake. It was a movement that Washington could not have stopped even if it had tried. The United States then had a population of 20 million (against 8 million Mexicans), and it was on the move. Furthermore, the Polk administration was openly expansionist and not conciliatory. Control of the westward movement became even more impossible after gold was discovered in California, whereupon its population in four years (1848-1852) zoomed from 15,000 to 250,000, nearly all of it located in northern California, and nearly all of it Americans. No government in Washington could have controlled that. Nor could the 5,000 Mexican residents of California. In an irony of history, the U.S. faced the same problem in the 1970s, as millions of Mexicans poured into the United States.

The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo (1848) at the end of the Mexican War set the border from the mouth of the Río Grande to the Pacific. The Gadsden Purchase of 1853 added to the United States a narrow wedge from El Paso to the Colorado River, to incorporate some lands at a lower altitude favorable to a transportation route. Thus huge territories, some of them barely explored and scarcely settled by Spain and Mexico, were transferred to the United States.

For an American and a Mexican view of the occupation of Mexico City, see

Paul W. Foos, A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair : Soldiers and Social

Conflict during the Mexican-American War. Chapel Hill: University of North

Carolina Press, 2002.

Luis Fernando Granados, Sueñan las piedras. Mexico: Ediciones Era, 2003.