by

This narrative is an excerpt taken from Chilenos in California by Carlos U. López, Palo Alto: R & E Publications, 1973. The original diaries of Chileno pioneers have been published by Edwin Beilharz and Carlos U. López We Were Forty-Niners, Pasadena: Ward Ritchie Press, 1976.

News of the Gold Rush reach Chile

News of the California gold discovery arrived in Chile on August 19, 1848, when The brig JRS anchored in Valparaiso. This ship, consigned to G. L. Hobson, a Valparaiso merchant, came from California with a load of hides and tallow. The captain reported a difficult trip, for he had lost half his crew. All the young men had deserted to go into gold fields, which were reportedly so abundant that to acquire the metal, one had only to bend over and pick it up. California was "all gold. " Strangely enough few people paid attention to the news, but when ten days later the schooner Adelaida arrived with $2. 500 worth of gold dust, the news spread all along the coast of Chile.

The first ones to react to the news were the foreign merchants. There was a large colony of American and English storekeepers in Chile who immediately realized the profits available in California. Barely two weeks after the arrival of the Adelaida, the frigate Virginian departed from Valparaiso, bringing to California forty-five English-speaking businessmen. Names such as O'neill, Hubbard, Armstrong, Ellis and Poett would make large fortunes in California that would eventually rival those of James Lick, Patrick Livermore and Faxon Atherton, all former residents of Chile who had established business interests in California. Most of these men were married to Chilean women and brought their families with them. Although few were born in Chile, a large percentage of them declared their adopted country as their motherland when questioned by the census taker. This first group carried with them most of the stock from their Valparaiso stores and set up shop as soon as they landed in San Francisco. The merchants continued to receive supplies from the port of Valparaiso which had extensive warehouse facilities where European and American merchandise was stored, awaiting the best prices in the area. The California gold rush was a great bonanza: shovels, picks, pans, cloth, gunpowder, liquor, shoes, etc., came to San Francisco directly from the Valparaiso storehouses.

The departure of the English-speaking "gringos" was the signal for the Chilenos themselves to join in the adventure. 1 First the professional miners, experienced tunnel and shaft diggers, collected their funds to buy tickets for California, whether on deck or in a cabin. When they could not gather enough funds, they would hire themselves out to rich entrepreneurs who were willing to pay for their passage. There were also those who became temporary sailors, stewards, and even musicians, so they could obtain passage in exchange for their services. A third group were the Chileno adventurers, people from all walks of life who wanted to make a fast buck. Among them were the prostitutes from Valparaiso and Talcahuano, most of whom would eventually marry and start families with long ramifications in California

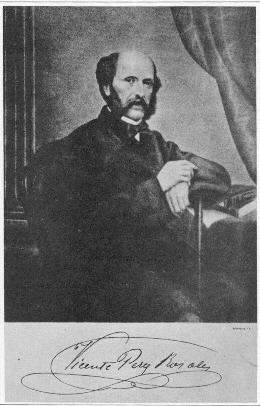

If the gringos, who were thought to be intelligent, hard-working and wise, had gone to California, why should the Chilenos stay home? After all, the country was in an economic crisis, opportunities were few, and as Perez Rosales, the most prominent of the Chileno 48'ers would say, "How can a rich man in Chile be a jackass?"2 Each ship that prepared to leave for California was filled to capacity as soon as its departure date was announced. In the first six months of 1849, the Chilean Foreign Office issued six thousand passports. After that, in view of the fact that half of the passengers did not even bother to get a passport, the Chilean Congress passed a law authorizing citizens to travel to California without passports.

Chilean shipowners, desiring to cash in on the windfall, spread all kinds of rumors about the fabulous wealth of California. Many a half rotted hulk was put back in service to go to California. The frigate Carmen, for example, a veteran of twenty years in the Pacific trade, was re-rigged and sent to California loaded not only with passengers and the usual merchandise from the storehouses but also with beef jerky, dried fruits, beans and even prefabricated houses. Soon the Chilean Merchant Marine fleet was laid up in California. By the end of 1849, ninety-two of 119 ships registered in Chilean ports were rotting in the waters behind the Golden Gate.

Little Chile

The first wave of Chilean emigration to California was ahead of all other nationalities except the Mexicans from Sonora, who came by land. Their arrival caused great surprise in San Francisco, and the local newspaper, the Alta California, explaining their presence by stating: "great excitement exists along the whole western coast of South America in relation to the gold mines in California. Great numbers of people are preparing to move here. "3

But the migratory fever had started to slow down in the first few months of 1849. Prices for agricultural commodities had risen to never suspected levels. Everything was being sold for shipment to California. It was precisely in those months that shipload after shipload of Forty-niners from the East coast of the United States, started arriving in Chilean ports after rounding the Horn. Talcahuano, the port of Concepcion, went through a flourishing period. In each house rum was sold, and the prostitutes had more clients than they could satisfy. Valparaiso shared a similar fate. If Talcahuano could count a dozen ships in its spacious harbor, Valparaiso accommodated over a hundred. A German captain tells of having counted 300 ships there in one day, including at least a dozen from Hamburg, his home port. Even the almost deserted islands of Juan Fernandez experienced a bonanza of commerce and trade, to the point that some Americans thought that the archipelago should be annexed to the Union.

If the enthusiasm of the 49'ers of every nationality wasn't enough, every ship that returned to Chile to pick up flour was greeted from the distance with the cry, "News from California" and answered, "Gold, much gold, gold in abundance. " These facts removed any doubts from the minds of the few remaining skeptics. Every Chilean who was able, took passage in the available ships. Chilean ship owners, who at first had been so enthusiastic, now faced bankruptcy for the ships did not return. No sooner did they anchor in Francisco than even the captain deserted, looking for gold . The brig Orión, for example, was abandoned while her captain, León Aguirre went on to become Nevada's pioneer cattle grower.

Perez Rosales, in his diary, and a few Chilenos, in their letters home, have left a picture of San Francisco much like the one painted by the English-speaking 49'ers: mud, lack of housing, gambling, few women, etc. Samuel Price, one of the early arrivals, became the self-appointed consul of the colony. Soon most Chilenos settled in a ravine by Telegraph Hill, in a square that today is limited by Montgomery, Pacific, Jackson and Kearny Streets. The place was known as "Chilecito, " or Little Chile, and Bancroft gives this description:

The space bounded by Montgomery, Pacific, Jackson, and Kearny streets was, in the spring of 1851, a hollow filled with little wooden huts planted promiscuously with numberless recesses and fastnesses filled with Chilians?men, women, and children. The place was called Little Chile. The women appeared to be always washing, but the vocation of the men was a puzzle to the passers-by. Neither the scenery of the place nor its surroundings were very pleasant, particularly in hot weather. On one side was a slimy bog, and on the other rubbish heaps and sinks of offal. Notwithstanding, it was home to them, and from their filthy quarters they might be seen emerging on Sundays, the men washed, and clean-shirted, and the women arrayed in smiling faces and bright-colored apparel. They could work and wallow patiently through the week provided they could enjoy a little recreation and fresh air on Sunday. Whenever a vessel arrived from a home port, the camping ground presented a lively appearance. Round the chief hut or tienda lounged dirty men in parti colored serapes and round-crowned straw hats, smoking, drinking, and betting at monte. Most of these were either on their way to, or had lately returned from, the mines.4

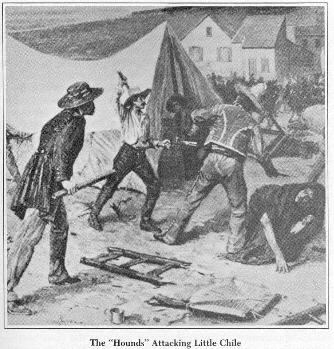

The settlement was sacked and robbed by the Hounds on July 15, 1849. These "Hounds" or "Regulators" as they called themselves, were a self appointed para-military group who had already tried to remove the mayor of the city. They were mostly malcontents and delinquents who had come to California with Steven's Regiment in 1847. In the spring of 1849 they were joined by the "Sidney Ducks" a group of Australians of similar backgrounds. They established their own headquarters in the corner of Dupont and Pacific and went out to drill. They also asked for "dues" from commercial establishments to finance their operations.

They asked Pedro Cueto, a Chilean merchant, to pay an overdue bill. Cueto claimed that it was not his bill and when threatened, he pulled out his gun and fired a few shots, missing the hounds but wounding a passerby. This was the spark that lit up the fires. After parading and stopping at every bar that would welcome them, the Hounds went to Little Chile ready to "cleanse the town of Chilenos."

"Down with the Chileans! Death to all of them!" was their war cry. Bullets went flying. Many people were wounded, almost all robbed of all their possessions. The place was sacked, the tents destroyed and fires set to everything that would burn. Many of the residents ran up the surrounding hills and some even took refuge aboard the ships anchored in the bay.

We don't know if there were many dead. There are no contemporary reports of any. But the clothes were stolen or burned, the furniture broken, the jewels and the money stolen. A good quantity of wine was found in a store owned by señor Alegría and the Hounds retired to celebrate the raid.

But next morning, the outraged population took action. Sam Brannan climbed the roof of his store and delivered a moving speech to request that decency, order and justice be restore. Citizens committees were organized and companies of armed men went out to arrest the Hounds. Twenty-four hours later, a jury convicted five leaders and sentenced them to jail. Since there was no prison available, they were detained on board a sloop of war anchored in the Bay. It was the first case of popular justice in San Francisco.

Chileans in the California and Federal Censuses

How many Chileans actually arrived in San Francisco has been impossible to determine. The 1850 Census did not include San Francisco or Santa Clara Counties, and it wouldn't be an exaggeration to say that in those two areas resided the bulk of the Chileno population in 1850. We must remember that in the summer month of 1850 the foreigners, Chilenos and Mexicans in particular, were expelled from the mines. We are told of "thousands" of Chileno returning to San Francisco. Still, the 1850 Census shows heavy concentrations of Chilenos in Calaveras and Tuolomne Counties. If they had been expelled from those places, wouldn't it be reasonable to suspect that at least double or triple that number had taken refuge in San Francisco waiting for passage home? The 1852 Census, a bit more reliable and taken by the state rather than by the Federal Government, shows no less than 1100 Chilenos in San Francisco alone, a figure that must be tripled when we consider the large number of Chilenos who lived in ships anchored in the bay and were counted as 'sailors' as well as those who refuse to give their names. We believe the Federal Census of 1860 to be more accurate, because the population had become less movable and because it seems to reflect in number the descriptions of the numbers of Chilenos by contemporary writers.

The Chileans in the Mines

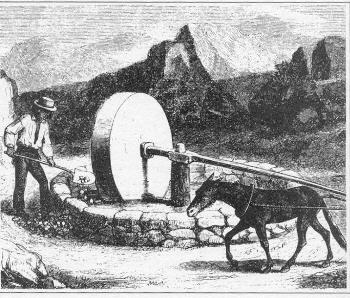

The Chileno miners went into the mines early. Most of them arrived in the last months of 1848. There they taught the "anglos" how to dig shafts and pan for gold, and how to select the most promising places. They also made use of some of the techniques they had learned in their native country: cracks in the ricks were picked with the long curvy knife, the "corvo;" sands were tested with the "poruña, " the hollowed horn of a cow or a steer. When there was not enough water to wash, they used the "aventamiento" method or "dry washing", and if the ore needed crushing, they improved the Mexican "arrastre" by providing it with a stone wheel and giving it a new name: the "Chili Mill. " It is interesting to note that these enormous stone wheels were hewn out of rock by very experienced stonecutters. Since a large number of them are still in existence today, we can presume there was a large number of Chilenos in this trade. However, the 1852 Census only lists two as "stonecutters . " This would indicate a very poor count among the Chileno residents of California.

Chilenos at the mines were concentrated into their own "Little Chiles. " There was a "Chilicamp" and a "Chilitown" besides the well known "Chiligulch" near Mokelumne Hill. This last was the scene of some bloody episodes in December of 1849. A certain Doctor Concha had established a camp in a gulch South of town. He had registered some of the claims in the names of his Chileno peons. Envious miners from Iowa, if we are to believe the Chilean account, tried to take over the diggings by force. The Chilenos retaliated and in the ensuing melee several were made prisoners. The Iowans executed four of them, whipped another half a dozen and cut the ears of the rest.

But that was the exception rather than the rule. Towns such as Sonora, Murphys, Hornitos, Hangtown, had a large contingency of Chilenos, which, in numbers at least, does not seem to be reflected in the Censuses. After the ill-treatment they had received, Chilenos were not too eager to be counted or identified. Unfamiliar with census-taking practices they either refused to give any information or made a joke of it. Of the first instance we have many examples in the official rolls: "25 Chilenos who refused to give their names;" "a large house of prostitution with 35 Spanish girls from Chile;" "357 Chilenos in a ravine;" etc. Of the second instance examples abound: a Juan Embroma, Too Cattoota, Juano Peona, and F. -Carajo among others, appear in the censuses. Several listed their professions as "Ell Cabroon" (sic. ) with various spellings.

Contemporary sources claim that most Chilenos, faced with the unjust treatment, the Foreign Miner's Tax and the competition of Mexican labor, left the mines. Some took to violence. Still, the 1852 and 1860 Censuses show large concentrations of Chilenos in the mining counties such as Tuolomne, Amador and Calaveras. But for the most part it must be agreed that by 1851 the "roto" had "seen the elephant, " picked up his pan and shovel and gone home.

"Bandidos"

Among the Chileno adventurers there was a fair proportion of people prone to violence. When they were expelled from the mines, they took up banditry. Some, like the famous Narrato Ponce, left a trail of crimes through the mines and the Central Valley. Others joined the gangs of horse thieves captained by Mexican outlaws like José California, El Gallo, and El Zorro.

Joaquín Murrieta, the celebrated bandit of California, was not a Chileno but a Mexican, in spite of the acclaimed drama written by Nobel laureate Pablo Neruda who erronously gives his birthplace in Chile. The confusion can easily be explained examining the "pirate" editions of Yellow Bid's original novel.

Chile supplies the gold miners

The ships, however, kept coming. Even if the stores of Valparaiso had been depleted, the rich Chilean central valley kept the California population from going hungry. In 1853 Chile was the leading country in exports to California: 127 ships with a total of 37,370 tons. The most important product was flour. Chileans mills in Concepcion province kept grinding grain twenty-four hours a day. But by then, the emigration was slowing down. From contemporary sources we must deduce that more than half of the Chileno 48'ers and 49'ers had returned home by 1855. The rest, at least 2023, if we are to believe the 1860 Census, remained in California.

Chileno achievements in California

At first, the Chilenos who remained constituted a very closely-knit group. Chileno newspapers were published in San Francisco from 1863 to 1883 and when Chile was threatened with aggression from Spain in 1865, "Chileno Patriotic Clubs" mushroomed all over California to collect funds to help the motherland. During the War of the Pacific, 1879-1882, the Chilenos contributed large amounts of money to the Chilean cause and actively engaged in propaganda at all levels. However, little by little they became anglicized. Most Chileno women married "anglos? as did a large percentage of the men. The Chilenos, for the most part, did not have to contend with the color prejudice of the black or the sharp Indian features of the Mexicans. Since a chance had been afforded to go home to Chile for those who wanted to return, only the best fit, the ones that loved California remained. Furthermore, throughout the turmoil and the abuse in the mines and in the cities, the Chileno demonstrated himself to be an unusually good fighter who met the "gringo" as an equal refusing to be pushed around.

The descendants of these Chileno Forty-Niners can not only be proud of the achievements of their forefathers but of their own: Entrepreneurs, judges, congressmen and other people who have left their tracks in the History of the State. Many of the San Francisco Streets carry names of former residents on Chile: Atherton, Ellis, Lick, Larkin and others. Chileno women also left their names: Mina and Clementina. Manuel Briseño, an early journalist in the mines was one of the founders of the San Diego Union. Juan Evangelista Reyes was a Sacramento pioneer as were the Luco brothers. Luis Felipe Ramírez was one of the City Fathers in Marysville. The Leiva family owned at one time, much of the land in Marin County, including Fort Ross.

Thus the Chileno achieved a high degree of respect. It is easy then to understand that unlike other minorities the Chilenos integrated quickly and like their "Little Chiles," they were soon absorbed by the ever-growing State of Californian, becoming part of the mainstream of the present population of the Golden State .

1 Residents of Chile were known in California as "Chilenos" rather than "Chileans" or "Chilians". Throughout this work "Chileno" has been used to denote a Chilean resident of California.

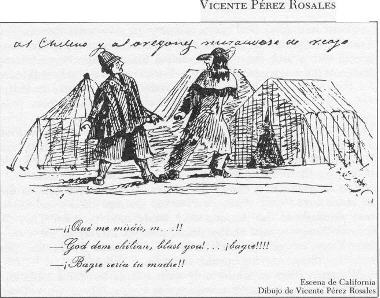

2 Vicente Perez Rosales, Diario de un Viaje a California, Buenos Aires: Editorial Francisco de Aguirre, 1971, p. 31. This is the only publication of the actual diary of the famous Chilean adventurer. Part of the diary is condensed in his Recuerdos del Pasado, first published in 1882.

3 News item in the Alta California, January 25, 1849.

4 Hubert H. Bancroft, California Inter Pocula, San Francisco: The History Co. S 1881, p. 261.