Editor: Judith Z. Marrs

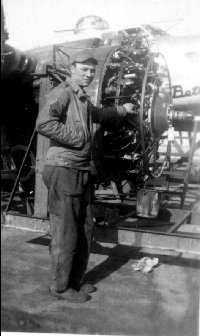

T/Sgt. Joseph W. Zorzoli

385th Bomb Group, 551 Squadron

Crew Chief, B-17 Flying Fortress

United States Army Air Forces

GI Joe Memories of WWII

I got married June 17, 1942 and turned twenty-one on July 26 the same year. Two days later I was no longer Civilian Joseph W. Zorzoli but was a soldier in the United States Army.

It was a sad day when my train pulled out for Fort Oglethorpe for my first eleven days of misery. I was put through all tests imaginable. After this, a buddy and I were put on another train and shipped to Miami Beach, Florida, United States Army Air force Base. For six days we went through more grueling tests and then were sent to Amarillo, Texas to a new aircraft maintenance school where we were educated in flight mechanics for six months. During this time my wife, Betty, came to spend Christmas with me, carrying our baby and looking like a balloon. She wanted a baby so bad, so if something were to happen to me in the war she would have something to remember me by. She stayed with me in Texas for eight days then returned to the home of her parents in Memphis where she stayed while I was gone to war. A few days after Christmas, twenty-seven other guys and I were sent to Boeing Factory to study the electrical systems on B-17s. Pretty good for a guy who did not complete high school, huh? After this, we were sent to Geiger Field in Spokane, Washington. This was where our squadron was formed. We were trained together, ate, slept and lived together for the duration of the war. We trained for two more months then left for England and arrived there July 6, 1943.

My first memory as a greenhorn soldier was the trip to England aboard the Queen Elizabeth. I had seventeen dollars in my pocket before I got involved in a black jack game, and by the time I realized we were passing the Statue of Liberty leaving the states, I was already flat broke. On the trip over, we sailed across the Atlantic unescorted. The Queen could do 35 knots while the German U-boats could only do eleven. That gave us great speed advantage. While on course, the English Navy manned the boat. It would zigzag every six minutes making it almost impossible for a torpedo to strike. On the third day of July a rumor was spreading around the ship that a German U-boat was picked up, and this was when we all got really nervous. The next morning on the 4th of July small guns began to go off. The queen was not built for wars. We sped to the deck and began asking what was happening. The English sailors replied, "We're celebrating the 4th of July for you Yanks." Can you imagine the English celebrating the Fourth of July for Americans? I found this quite ironic and typical of the British dry wit. On July 6, the Queen docked for the night in Glasgow, Scotland. It was late afternoon, and lots of small boats gathered around the Elizabeth with people on board calling for American cigarettes. We threw them over the sides and children dived in after them.

The Queen Elizabeth was an exquisite ship, but it was unfinished in the staterooms when we crossed over. Her sister ship, the Queen Mary, was identical and just as beautiful. They were built by the English for passenger service between the states and Europe and made numerous voyages after the war. Years later a company in California bought the Queen Mary and docked her there, making her into a museum, a beautiful nightclub and several elite restaurants. It was strictly a tourist attraction. I don't know what happened to the Elizabeth, but it is probably in England somewhere. They have both been dry docked and taken out of service. Air transportation seemed to make them obsolete for travel. During the voyage over, I couldn't help but think about my parents who were Italian immigrants that crossed the Atlantic for the United States during the early 1900's. My mother was very young, maybe 12 or so, and the day after her crossing the Luisitania was sunk. My father and mother came from the same small town in northern Italy, Mede, but never met until they were working on a truck farm owned by relatives in Memphis. It's a small world I guess. Back to the War.

We unloaded from the boat in England and boarded a train going to Great Ashfield, about 80 miles southwest of London. This was to be our base home for the next two years. It was in the country away from the big cities. We were the fifth group to arrive in England. We were the Strategic Air Command, which means heavy bombers, and we struck German industrial areas at night. There were sixty of these groups stationed in England which accounts for about 800 B-17s total. There were also B-26 MEG bombers and P-47 and P-51 flight planes. I would estimate about 100 air bases totally. These bases were costing the United States government $750,000 a day for each individual base so one can see how much money the English made from us while we were over there trying to save their skins. But if we had not been there and stopped the Germans, we could all be saluting the German flag today. It was a great joint effort with the Russians joining in to help. We saved the world from being enslaved by the Germans, and thank God it turned out as it did.

My duty in the Army Air Corps was to maintain the airplanes in flying condition. I was the only person who could ground the plane and say it was unsafe for flying. This was the crew chief's responsibility...that was the law. Around four o'clock a.m., before take-off time, I would take a mechanic and go out to the plane and do a pre-flight. One of these times almost cost me my life for the first time. I went out as usual to do the pre-flight before the aircrews arrived for take-off. A pre-flight is merely a double check of what you did at the end of the day before. You start the engine, check the MAG's RPM manifold pressure, brakes and all the flight controls. There is a gun turret behind the pilot and co-pilot. Oxygen and power have to be supplied to the turret for the gunmen operating it. The oxygen and electrical line came in contact and caused a fire. Like an acetylene torch, fire was going everywhere. Komar, the boy who was helping me, went out the front hatch. I did not see him because it was dark at two in the morning. When I jumped out and started to run, I crashed into a barbed wire entanglement that surrounded the ammo dump where the bombs were stored. I could not get out. The more I pulled, the more I was snared by the sharp clawing wire. All I could think of were the ten 500 bombs and the 2000 gallons of 100 octane gas in that plane. I knew it was ready to go any minute. I finally managed to escape the barbed wire and started running. I made it to the runway when the explosion went off. Komar had already made it to the engineering office, and Captain Myers, my officer, was asking where I was. Komar said he did not know because he left the plane first. Captain Myers and I had been good friends and golfing buddies so he was afraid of the worst. When I finally walked into his office, he grabbed and hugged me and said, "Boy, Am I glad to see you!"

Several of the planes under my command, I'll always remember. The Raunchy Wolf was the first plane I maintenanced. We trained with this plane in the states, then flew to England for combat duty. The pilot was a Jewish boy, 1st Lieutenant Erwin Franks, from Florida. Franks was the first one in our group to complete 25 missions, second behind the famous Memphis Belle. The plane and crew flew back home to tour the states and promote the sale of war bonds.

Juniorwas my second plane, and it was shot down on its 28th

mission. Before it was lost, Captain Sherrill from Carruthersville, Missouri, completed

his 25th mission, then went back to the states. On its 28th mission, it was shot down over

France. At this time the pilot was Lieutenant Fry, a small, young man 22 or 23 years of

age. Fry and the tail gunman managed to bail out and hid in a haystack until nightfall.

When they finally started down the road, they were picked up by members of the French

Underground and were kept hidden for about three months. Then one especially dark night

they were transported to an open field, and a small English aircraft picked them up and

flew them back to England. They returned to the base at night, and Fry came to tell me

about the ordeal. I had assumed he was dead and felt as if I was seeing a ghost. After

seeing the expression on my face, Fry said, "Oh no, you thought I was dead." He

informed me that he and the tail gunman were the only two who bailed out. Fry stayed

around a few days and was sent back to the states because once one was shot down and

gotten out by the French Underground, one was never put back into combat flying again. The

reason for this was so not to jeopardize the work of the French underground by trying to

reach them.

Off Spring was my third airplane. It was

downed by a mid-air collision with another plane. I don't know the other plane involved,

and I didn't even know that eighteen perished and that two survived until I was told 50

years later in a letter. I did not know it happened in the Luxembourg area either. I would

like to know what happened to the two survivors. Off Spring got its name from one of the

crewmembers because his wife had just had a baby. What was so sad was he never got to see

his baby. Off Spring only flew five missions before its tragic ending.

The next airplane didn't last long enough to be named, because it was shot up on its first mission. I think they made it to Switzerland and interned for the duration of the war. As you probably know, Switzerland was a neutral country during the war and if one ended up there, one had to stay. I really don't know this for a fact; I just assume this is what happened because I never heard a word from the crewmembers again. If a plane was shot up bad during the war and could not make it back to the base in England, the pilot usually headed for Switzerland. I imagine a few headed for Switzerland just to get out of the war. They were paid regular pay, $7 a day, then stayed in Switzerland; it was like a vacation.

My last airplane was named after my baby girl, Betty Jo. The pilot decided on the name. He was a fine man from California. On our first mission, we flew to Linz, Austria to pick up some Belgian boys that had been held captive for five years. We loaded 35 to a plane and headed to Chintilly, France where we to unload. While in transit, I was taking a nap between the pilot and co-pilot when suddenly one of these boys was shaking my leg. Neither of us could understand the other, but he managed to get me up in the nose of the plane as we were flying over a small village. He pointed to a wedding ring on his finger, so I figured he was trying to tell me that his wife lived in that town. He had the biggest smile on his face. Keep in mind, these boys had been away from home for five years. Some had children five-years-old whom they had never seen. When we landed in Chintilly, there must have been 400 people there waiting for their loved ones they had not seen in five years. I felt like crying for joy for these people. I must say, this was the most rewarding experience in my lifetime, seeing the reunion of these families. God bless them all. The Betty Jo flew 78 missions without an aborted flight. For this, I was awarded the Bronze Star.

I had two furloughs while in England. The first year I went to Edinburgh, Scotland which is a beautiful country with very fine people. Two of my buddies who were my best friends went with me. One of them was David Coons who was my age and from Albany, New York and worked for Montgomery Ward before coming into the service. My other friend, Ralph Leirch, was ten years older than Dave and me. He was a milkman in civilian life and delivered house to house which they no longer do. His home was Orange, New Jersey. All of us were from different parts of the country, but we were very close. Even after the war ended we stayed in touch, but as the years passed we got busy raising our families, and the correspondence dwindled to Christmas cards once a year. As I think back, we had lots of fun on furlough. In Scotland, we stayed with an elderly lady who had a beautiful home, and it still amazes me how they shined those big brass door knobs every day. The Scots were very strict on cleanliness. If there were slums or run-down neighborhoods, I did not see them and I was all over Edinburgh. The lady would wake us at 7 a.m. with breakfast ready which consisted of two eggs, fried strips of fish instead of bacon or sausage, two pieces of toast, orange marmalade, and hot tea. Lunch and dinner we always ate out. There was a shortage of food, but what they served was very tasty. We walked around town or rode the tram. Princess Street was like Main Street in any large town, but it was on the outer edge of the city. You could see the castle from up on the hill. The long winding street, bordered by a four-foot wall, led to the castle. We took in all the tours that were very interesting. We viewed the bed of Queen Mary, which was still intact, enclosed in a glass vacuum. It was magnificent. We saw the guillotine where the queen chopped off Henry's head.

Edinburgh was where I met Helen. That's another story.