|

3: Pablo Beach, 1907-25

<< 2: Pablo Beach, 1886-1907 || 4: The World's Finest Beach, 1925-45 >>

Now the tiny community by the sea was the Town of Pablo Beach,

not just a rural post office. It was now an official entity, a way

to collect revenue and

provide for the common good of residents-permanent and summer-and

tourists. The Town could effect changes. It could encourage growth.

Government money, not its own, would determine the Beaches future. To live

outside the public budget is to live in error. Pablo Beach officials knew the

score.

The new government supported the digging of

a canal through the Diego Plains to connect

San Pablo Creek to the Tolomato River near St. Augustine in 1908. The

Florida Coast Line Canal & Transportation Company (FCLC&TC), organized

in the 1880s, finished dredging a canal in 1912 but it was unsatisfactory. The

undertaking was taxing. The

national government eventually assumed responsibility and, by 1935, had

produced a 100-feet wide and 8 feet deep canal.1

Canal proponents hoped that the canal would be a commercial thoroughfare and

improve the local economy. In the early 20th century, however, not

much would be shipped from the St. Johns River to St. Augustine.

In the early 1900s, the Port of Jacksonville grew when the shipping channel was dredged to

24 feet and then 30 feet to allow bigger ships. Jacksonville truly became an international port.

The St. Johns originally only had a clearance of 3-4 feet, but bigger ships

drew more water. Improving the river took years of lobbying by private enterprise

to get governments to pay the costs. In 1879, Congress appropriated funds to

build the jetties, necessary to create a controllable channel at the mouth of

the river. In the 1890s, the Jacksonville

Board of Trade, as the Chamber of Commerce was then called, got Duval

County to authorize $300,000 to dredge an 18-foot channel. In 1902, Congress

paid $2.1 million to have it dredged to 24 feet which was done by 1907. In

1910, a 30 foot channel was dredged. In 1912, the U.S. House of Representatives

demanded that City of Jacksonville government build city-owned docks,

terminals, and warehouses before it would spend any more money on the river.

The existing facilities were so bad that Congress decided to force a socialist

solution because a viable port was of national importance and it was clear that

the private sector would not or could not build the necessary facilities.2 Jacksonville smelled the money and

complied. Money talks, as they say.

Money came when the film industry came to town in 1908.

Jacksonville was a winter film center more important than Hollywood as

film companies came south to escape the cold and

to pay lower wages. The abundant sunshine and mild weather made

northeast Florida a welcome respite from the harsh winters of New York and

Philadelphia. First to arrive was the Kalem Studios but others followed as word

spread. At its peak, there were thirty companies with studios. Oliver Hardy and

Lionel Barrymore starred in silent movies made in Jacksonville.3

Writing about a Kalem film company trip to Jacksonville in 1908, Gene Gauntier,

a writer, actress, and producer said:

Within a few hours of our home were

quaint negro villages, their unpainted huts set on stilts above the shifting

sands. There were wonderful stretches of sand at Pablo and Manhattan Beach, facing

the open sea, uninhabited and desolate, with their scrubby palmettos, which

served as setting for many desert island scenes. There were fishing villages,

primitive as even a picture company could wish, quaint old-time Florida houses

with their "galleries" of white Colonial columns, orange and

grapefruit groves, pear and peach orchards which gave forth lovely scents when

in full bloom; formal gardens and Spanish patios; the gorgeous Ponce de Leon

hotel and gardens, and the picturesque old fort at St. Augustine.4

Money did not talk loud enough. The film industry created problems in the

Jacksonville area and met enough resistance that it gave up and concentrated

instead on the desert of southern California. Perhaps the Beaches would have

been more tolerant but many Jacksonvillians could not tolerate the behavior of

movie people. Their personal lives were often blatantly messy; they disrupted

normal life with the filming of car chases and shootings. For those in

commerce, too many did not pay their bills on time. Banks would not extend credit

as needed and film making, like farming, is done on credit.

World War I disrupted the movie business

because it diverted money and attention to the serious business of killing.

After the War World I, a few movies were made in Jacksonville but the time had passed.

Decades would pass before parts of movies were shot in the area.

The Beaches relied upon tourism for income, not the movies, and

the opening of Atlantic Boulevard to great fanfare on July 28, 1910 provided a

viable alternative to the FEC train. There was

a parade and the dedication of bridge spanning Little Pottsburg Creek, which was

close to the St. Johns River and marked an obstacle to the Beaches. On the

shore, auto

races were held in front of Continental Hotel in Atlantic Beach. The railroads monopoly of

transportation to the Beaches was broken. Automobiles were the future.

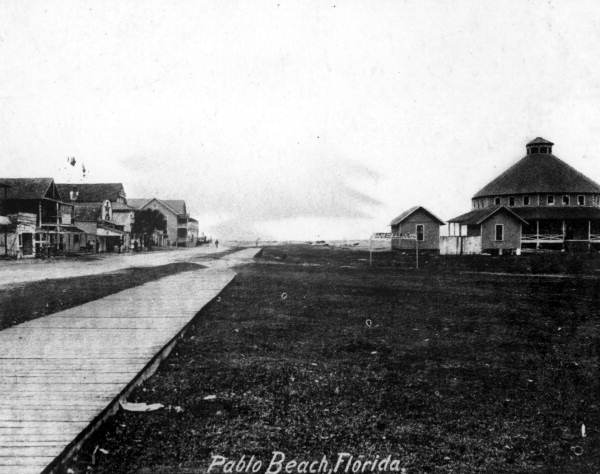

Figure 3-1 Pablo Beach in 1906. The Pavilion on the Right

Atlantic Boulevard was long in

coming. Soon after the railroad was completed to Pablo Beach in 1884, E. F.

Gilbert acquired land at Beaches that he wanted to develop. He needed a wagon

road from south Jacksonville to Pablo Beach. He paid a surveyor to mark a route

and then got the county commission to start work on the road using convict

labor. The project, started September, 1892, completed two-thirds of the route

grade and the bridge across Pablo Creek before the county commission changed

its views and stopped the work. In 1902, Fred E. Gilbert, son of W.E. and an

automobile dealer, lobbied to get the road finished. After popular auto races

at Atlantic Beach in 1906, he finally generated interest in a paved road but

the Panic of 1907 intervened. In 1908, work started but only as a shell and

brick road. Cars began using it 1908 but the completion and dedication had to

wait. By 1922, it needed repair and the St Johns River had been spanned, thus

eliminating the cumbersome and expensive ferry service. The road proved to be

so valuable that, in May, 1923, the county passed

a bond issue of $2.55 million to build a concrete, lighted

highway. Atlantic Boulevard would become a marvel that allowed rapid access to

the Beaches.5

E. F. Gilbert got things done. He

was originally from Connecticut and a U.S. Army veteran. His primary occupation

was being a jeweler but he was also a land speculator. He bought six parcels of

land at Neptune Beach and wanted a better way to get there. The train would

only stop at a station so he built one in 1910 in the section of Pablo Beach

known as Neptune.6

Neptune, the northernmost section of Pablo Beach was replatted in 1911. It extended

into present-day Atlantic Beach.7 This

would become the basis of Neptune Beach, created in 1931.

South of

Pablo Beach, another development, mining, was occurring in 1912. No one could

anticipate how the exploitation of these sand dunes to extract rutile,

ilmenite, and zirconium (all useful for making steel) would become Ponte Vedra

Beach.

Instead, the firm of Buckman and

Pritchard, Inc. of Jacksonville began to mine the minerals. It built a post office, store,

and workers quarters.It also built a nine-hole golf course for its management.8

Close by in a slightly more western section of St. Johns County was the older but more fragmented

Palm Valley. People has been living in this area,part of it was the Diego

Plains, since the 18th century but in houses far apart. It was a hard

scrabble life as settlers did subsistence farming, hunting, and fishing. People

cut palm leaves to sell and ship from the Durbin Station on the FEC until they

used the Intracoastal Waterway, which was finished in 1912. Those fortunate

enough to go to school had to travel north to Pablo Beach for the community was

far from the county seat of St. Augustine and there was precious little in

between. As late as the 1950s Palm Valley was considered backwoods. Ernie

Mickler, author of White Trash Cooking, grew up there.9

It was the neighboring mining camp that would eventually grow but not until the late

1930s.

Various improvements were made to

Pablo Beach as a beach resort. In

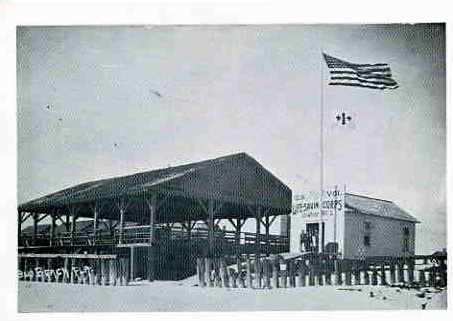

1912, the Red Cross Volunteer Life Savings Corp was created. Tourists, who often

did not understand the vagaries of the sea, needed help. Drownings

discouraged visitors. No one could have foretold that this Red Cross Volunteer

Life Saving Corps would still exist in 2006. The pier provided a place for visitors to dance, relax, and

fish. Lifeguards found the pier problematical because bathers often did not

understand that razor-sharp barnacles grew on the pilings. In 1925-26, Martin G. Williams, Sr. built dance pavilions, restaurants,

shooting galleries, and other amusements on the new boardwalk. In 1916, the

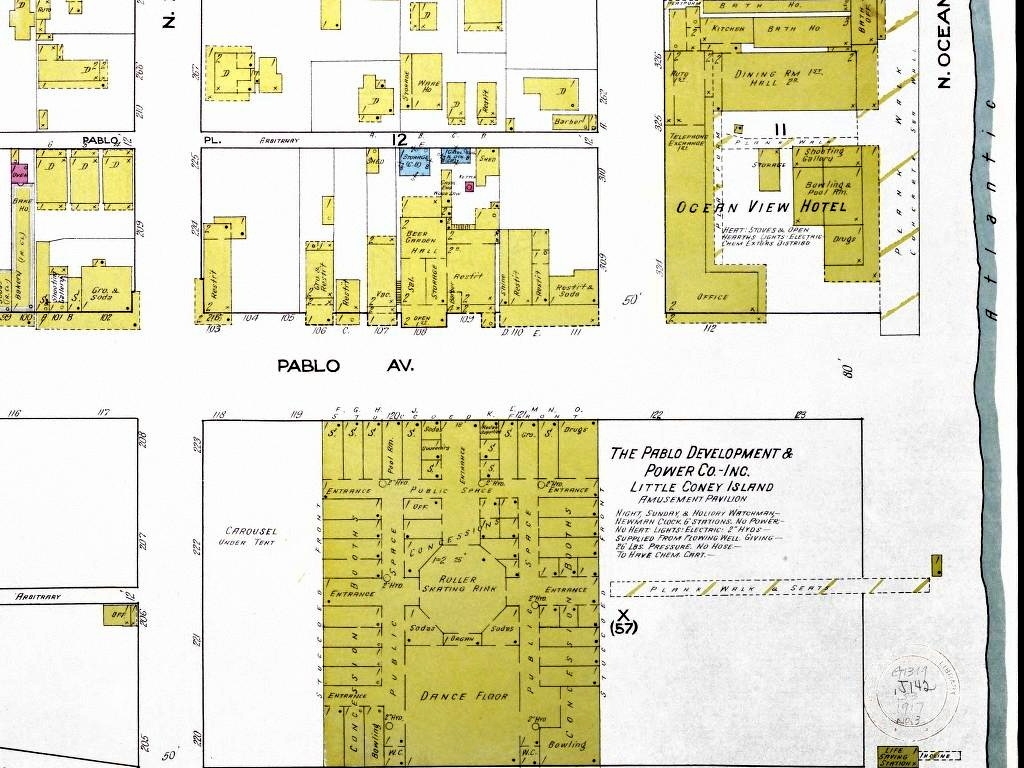

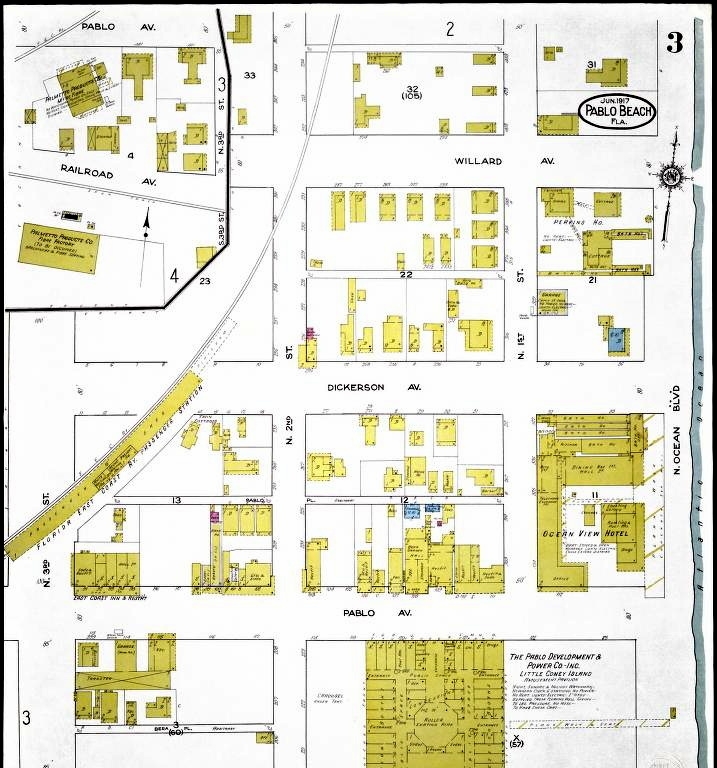

Pablo Development and Power Company created Little Coney Island which opened in 1917. This amusement center attracted more tourists. It was located where the dance pavilion had been. Little Coney included a bowling alley, a dance floor, a pool room, stores, and a roller skating rink.11

Figure 3-2 Lifeguard Station, 1912

Figure 3-3 Shad's Pier, 1922

Figure 3-4 Pablo Avenue, June, 1917

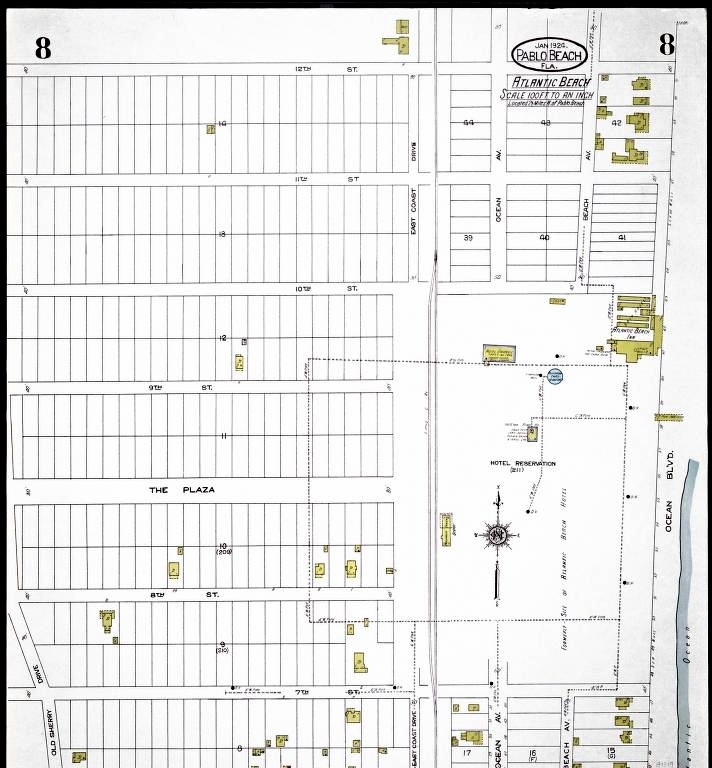

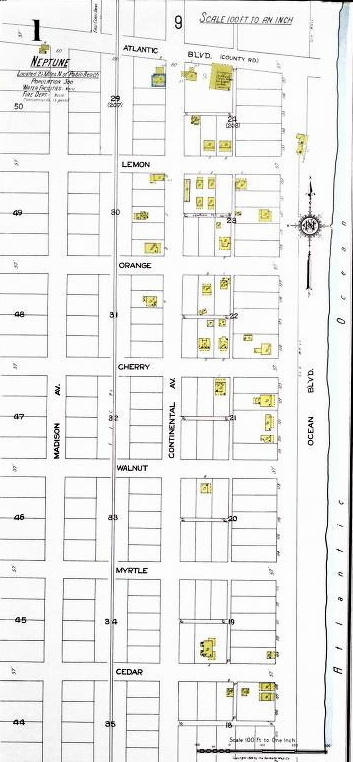

The 1917 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map

shows houses, cottages, the apartments of Finkelstein Flats, the Palmetto

Products Company, stores, bars and beer gardens, the Ocean View Hotel a public

elementary school, Perkins Hotel and Bath House, a grocery store, the train

station,

and various other buildings.

Private homes are only shown when they are in proximity to public buildings.

The town had grown and had begun to have other than wooden buildings. The

Perkins House, which became the Perkins Bath House, was a frame house operated by Mary E. Perkins.

Eventually, she added more buildings. When a fire consumed it, she and her

daughter, Anna Pursel, rebuilt a more substantial structure.

Figure 3-5 Railroad Station, Perkins Bath House, Ocean View

Hotel, Little Coney Island

Figure 3-6 Perkins House

Figure 3-7 Perkins Bath House and Rooms, 1930s

World War I affected the Beaches in

two ways. After the U.S. entered the war in April, 1917, the national

government brought 21,000 soldiers to Jacksonville to Camp Johnston in October

and November.12

The beach was one place they went to relax.

US military involvement lasted on 17 months because an armistice was declared

on November 11, 1918 so the tourism impact was not very great.

A number of Beaches men served in World War I. From Atlantic Beach, there were five men: in the Navy, Crawford James Gilbert (white) , in the Army, John Jackson , Alexander Killen, Alexander Kirkland, and Willie Webb, all of whom were African American. From Mayport, in the Navy, Otto Ernest Burford, George McCauley Daniels, Neal Florence Daniels, Claude Sidney Davis, Alonzo C. Greenlaw, Herbert Austin Harris, Milton Lewis Harris, Addison Thomas Haworth, John Franklin King, George Allan Leek, Alexander Better Thompson, and Stephen Coleman Truesdale. To the Army, Mayport contributed William C. Aiken, Franklin Arnau, Walter Colman Arnau, John C. Bleight, Clarence Coward (Negro), F. A. Daniels, James L. Floyd (Negro) , Fred Dickson Haworth, George Hilgerson, Edmund Mosley (Negro), George William Murwin, Arthur Francis Sallas, Chauncey J. Singleton, Holbrook E. Singleton, Robert E. P. Singleton, Oscar F. Thompson, Jeremiah Walker (Negro), General Williams (Negro), and George Williams (Negro). From little Pablo Beach, the Navy got Eugene George Zapf while the Army got Ernest Atkinson, James Robert Barbour, Porter R. Barnes (Negro), Samuel G. Barnes (Negro), Herndon Hollinsworth Hall, William Howard Jeffcoat (Negro), William Fletcher Jones, George T. Leonard, and Carl Ulrich Smith. From Palm Valley there was Sidney Alexander Mickler who served in the Navy.13

Town

|

"Black"

|

"White"

|

Total

|

Atlantic Beach

|

4

|

1

|

5

|

Mayport

|

6

|

25

|

31

|

Pablo Beach

|

3

|

7

|

10

|

Palm

Valley

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

Totals

|

7

|

30

|

47

|

|

|

|

|

|

Military pilots used the

hard-packed sand as an ideal runway for airplanes, a new phenomenon in the

world, as they experimented with transcontinental flights. On December 22,

1918, Major Albert D. Smith and three other Army aviators landed on Pablo Beach

in Curtiss JN-4 biplanes. It had taken 18 days from San Diego. Then, on

February 24,1921, Lt. William Devote Coney landed at Pablo Beach after making a

flight from San Diego, California inn 22 hours, 17 minutes. His return trip

began March 25, but he crashed and died near Cornville, Louisiana. That same

year, Lt James Doolittle left the Neptune Beach portion of Pablo Beach on a

transcontinental flight to San Diego in 21 hours and 18 minutes.14 Doolittle later became famous for leading bombing raids on Japan during World War II.

The first half of the 1920s was an

exciting time for Pablo Beach. Getting to the Beaches became easier on July

1,1921, when the Jacksonville-St. Johns Bridge (Acosta Bridge) was opened.

Automobiles, trucks, busses, and pedestrians could cross the St. Johns River

without using a ferry or a train. In 1920, the beach community passed some

morality laws because a New York female beauty had shimmied in a

"revealing" bathing suit. Town officials passed laws to outlaw

shimmying, cheek-to-cheek dancing, and wearing any but a two-piece bathing

costume with a skirt at least a foot long. Prohibition had become law in January

and Pablo cops were told to spy on people and where they stayed to make sure

they did not imbibe, searching even

without a warrant, to make sure that no alcoholic beverages were being owned or

consumed. In 1923, however, opinion must have changed because Pablo Beach

was inundated with tourists because the town's Board of Trade had been

advertising the town as a resort and could not handle the number who showed up.

Earler, in 1922, the Town of Pablo Beach had become the City

of Pablo Beach. Residents of the Neptune area in the north considered seceding, however, for they were separated by several miles were more oriented

to Atlantic Boulevard. On March 14,

1923, Pablo Beach joined the Jacksonville electrical system. The Duval County school board built a new grammar school

for "whites" in 1924, a school that building served the community for decades.

The Pablo city government started building a new city hall which was completed

in 1926.15

In 1922 and after, the Beaches

communities made a big push to increase tourism. To encourage this industry

without chimneys, they paved the road between Neptune and Jacksonville

Beaches, built seawalls or bulkheads, and installed

street lights to illuminate areas near the strand.

They bridged a slough in south Jacksonville

Beach. They got daily bus service from Jacksonville to Pablo Beach started by

the Seminole Auto Bus Company.16

To promote tourism, a swim suit competition was staged

at the Pablo Beach pavilion on

June 6 , 1924. The American Legion Post # 9 sponsored the Delegation of Mermaids at the Revue of Modes and there were

twenty-five women contestants who were said to be modeling swimsuits. Pathe

News was to film the event. The suits were borrowed from the Mack Sennet film

studio. Pablo Beach mayor Joe Bussey proclaimed the day American Legion Day

and thousands came, perhaps 7,000. A local woman, Mary Gonzalez, won.

All was not

well at the Beaches, however. On December 22, 1922, the Ku Klux Klan entered

Florida through Jacksonville. Its largest Klavern was Stonewall Jackson No. 1

of Jacksonville and it joined other Jacksonville civic groups to protect

city beaches from commercial exploitation.17

The Klan would remain strong throughout the 1920s. It gained many

supporters in 1928 when the Democratic Party nominated Alfred E. Smith for

President, a Roman Catholic. Those who supported Smith were harassed including

the police chief.18 The Klan

opposed most of Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Asians, Africans, most

Europeans, urban mores, and African-Americans. They also wanted to enforce

Prohibition. The Beaches had their share of

bigots.

When

the Florida Land Boom hit, people dreamed of growth. Such was the case of the

development to be name Ilanda. It was to be an upscale development sitting

astride the Intracoastal Waterway north of Atlantic Boulevard. In 1925, F.L.

Tucker was the general manager of the Ilanda Development Company. His grandiose

and expensive plans matched the euphoria of the land boom. Like it, however, it

went bust. Ilanda was never built.19

In 1925 as well, Gabe Lippman

purchased half a mile of ocean front between Jacksonville Beach and Atlantic

Beach to add to the land he owned west of the two beaches. His property

consisted of 2,500 acres and stretched to the Intracoastal Waterway. Lippman

planned to build a town with a golf course, hotel, pier, and yacht basin. He

built Florida Boulevard in what is now Neptune Beach to run from the ocean west

and then northwest until it intersected with Atlantic Boulevard at the Mayport

Road. He had to fill many low spots and constructed a miniature railroad to

haul the fill. He held a big celebration on July 2, 1925 at the

ocean front but little had actually been

done. In October, he sold the project to the Majestic Homes Corporation of St

Louis. It planned to create a 25,000 person city but Florida Beach was never

developed. When Majestic Homes defaulted in June, 1926, only a few homes had

been built.20

Growth would be incremental. In Mayport with its 644 people in 1925 survived on its

coal docks for the FEC Railroad, a menhaden (pogey) plant, boats such as the Hesse

making the Jacksonville loop, fishing, and the dredges for the St Johns River

and Pablo Creek. The tiny commercial district included Annie Daniels hotel,

boarding houses, watering holes, and food purveyors. The Atlantic Beach Hotel

burned in 1919 but W. H. Adams, Sr. bought the property and built a 50-room

stucco hotel which opened in June,1925. An outdoor swimming pool was added in

1929. Atlantic Beach was incorporated in 1925 but less than 150 people lived

there in houses near the Hotel.

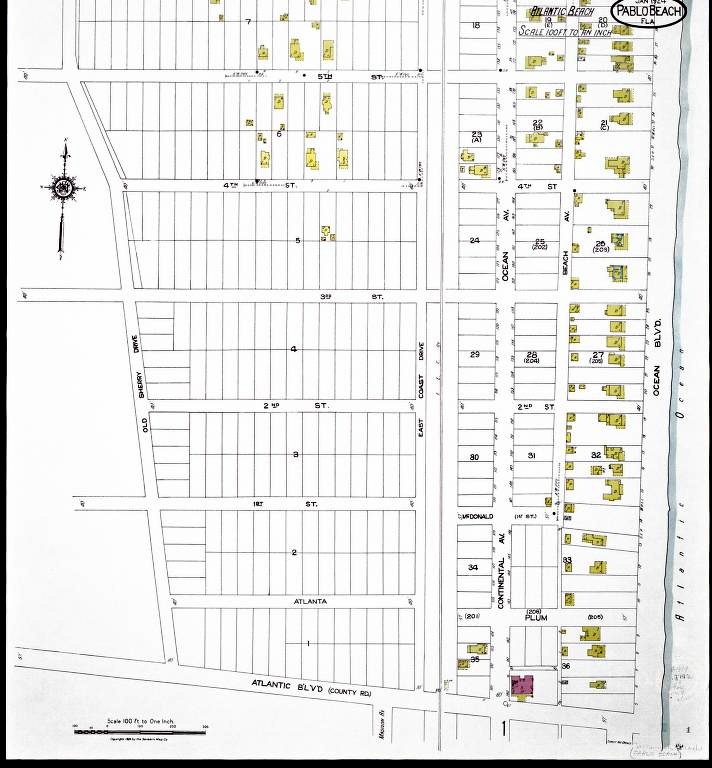

Figure 3-8 Atlantic Beach, 1924

The year

1925 was momentous for Pablo Beach. On February 9th a mass meeting

to rename Pablo Beach to Jacksonville Beach was held. The city council ratified

the decision with 75% wanting to change. Residents decided their future lay

with being associated with the city to the west hoping it will mean growth for

their little city. grow. The government also extended the city limits west to

Pablo Creek, north to Atlantic Boulevard, and one mile further south. 21

The little

city of 744 people had grown from a few tents to substantial buildings. The

Roman Catholic Church had a convent. North of the Episcopal Church on the same

block was the Friendly House, a home where young women could stay. St. Andrews

African Methodist Episcopal Church had been built at the corner of Shetter

Avenue and 7th Street South, the focal point of the "black"

community. To the west of 3rd St and south of the railroad, the African-American

settlement had grown. Besides the downtown area, the city extended south about ten

blocks and west about eight blocks.

To

the north, the city extended about a mile with scattered houses and then

skipped further north to Neptune and its few houses.

Figure 3-9 St. Andrews AME Church, 2006

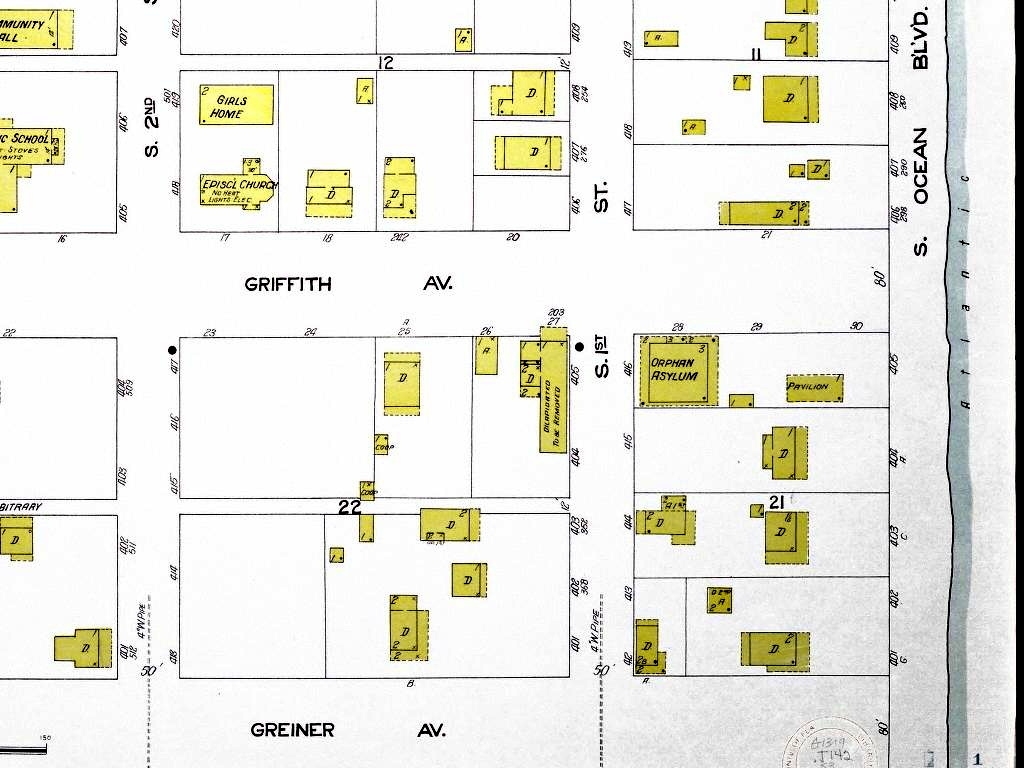

Figure 3-10

Orphan Asylum, 1924

Figure 3-11 African-American Neighborhood

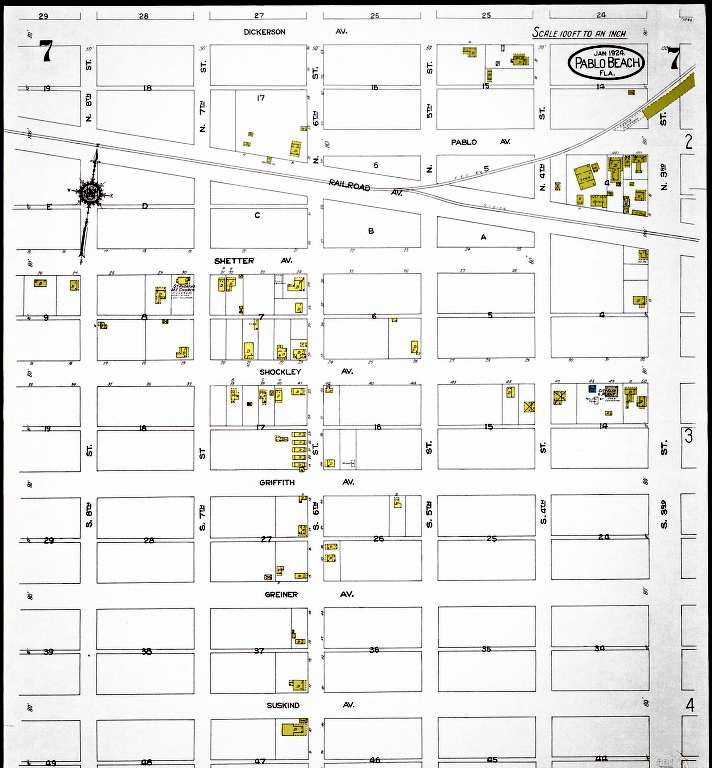

Figure 3-12 Neptune, 1924

Pablo

Beach was now Jacksonville Beach; it had hitched its wagon to the Jacksonville

steed. Jacksonville had 91,558 people in 1920 and 155, 503 in 1930, an increase

of 179%. It was a good bet. Lighted, paved Atlantic Boulevard, opened in 1925,

began replacing the FEC railroad as the umbilical cord to Jacksonville.

Endnotes

1. Johnston, Architectural Resources, pp. 89-91. In 1882,

people knew that a canal was needed. The Floripedia

Web site quotes "An Ocean Voyage in

Winter," in Chapter 11 of Florida for Tourists, Invalids, and Settlers, 1882 to the

effect that no good harbors existed except Fernandina and St. Augustine. The

pamphlet proposed a canal using existing waterways and building canals, starting

from mouth of Pablo Creek at St Johns River. The Palm Valley Bridge was

completed in 1937. The Intracoastal never became a major waterway for freight

but pleasure craft used it often. Traveling on Atlantic Boulevard and, after

1949, on Beach Boulevard, could mean waiting until the drawbridge was raised and

lowered for a motorized sailboat or large cabin cruiser.

2. James B. Crooks, Jacksonville

After The Fire, pp.28, 65-66.

3. Crooks, Jacksonville After The

Fire, 1901-1919, p.29; James Robertson Ward, Old Hickory's Town: An Illustrated

History of Jacksonville. (Jacksonville: Florida Publishing Company, 1982),

pp. 188-195.

4. Gene Gauntier, "Blazing the

Trail," Woman's Home Companion, Volume 55, Number 11, November 1928,

pp. 15-16, 132, 134.

5. Bill Foley, "Atlantic, Girvin Met

on Road in 1910," Florida Times-Union, July 25, 1998; Davis, 237-239.

6. Bill Foley, "A Typical Yankee to

Thank for Road," Florida Times-Union, August 20, 1997.

7. Johnston, Architectural Resources, p. 53.

8. Elaine B. Koehl, The Ponte Vedra Club: The First

Fifty-Five Years, 1927-1982. (Ponte Vedra: Ponte Vedra Club, 1982).

9. Michel Oesterreicher, Pioneer

Family: Life on Florida's Twentieth-Century Frontier. Tuscaloosa: The

University of Alabama Press, 1996. Ernest Mickler, White Trash Cooking.

Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 1986. Oesterreicher and Mickler attended Fletcher

High School at the Beaches.

10. Johnston, Architectural Resources, p. 53.

11. Bill Foley, "Trains A New Idea?

Sure Back in 1916," Florida Times-Union, January 28, 1999.

12. James B. Crooks, Jacksonville

After The Fire, 1901-1919: A New South City. Jacksonville: University of

North Florida, 1991, p. 120.

13. World

War I Induction Cards., The Florida Memory Project. See Donald J. Mabry, "Jacksonville Beaches & Mayport WWI Veterans" on the Historical Text Archive for an

extensive treatment.

14. Johnny Woodhouse, "Doolittle

Took Up Challenge After Coney Died," Times to Remember: A Calendar for 2005. The

Beaches Leader, 2004; Davis, 279, 282.

15. Bill Foley,

"Millennium Moment: June 2, 1920: Vexing vixen's shimmy shocks Pablo

Beach," Florida Times-Union, June 2, 1999; Davis, 324, 330;Johnston,

Architectural Resources, p. 59; Bill Foley, "Tough Decision: Boxing or

Swimsuits? "Florida Times-Union,

June 3, 1998; Johnston, Architectural Resources, pp. 60-62. The school was Jacksonville Beach Elementary

School which was eventually demolished. What was the elementary school for

African-Americans then was named Jacksonville Beach Elementary School. Bill

Foley, "Millennium Moment: July 24, 1923: Possibilities for Pablo Beach

were endless, " Florida Times-Union, July 24, 1999.

16. Johnston, Architectural Resources, p. 59.

17. David Chalmers, "The Ku Klux

Klan in the Sunshine State: The 1920's ," Florida Historical Quarterly

42:3, 210-216.

18. Oesterreicher, pp. 91-95.

19. Bill Foley, "Ilana, The Dreamers

Resort That Never Was," Florida Times-Union, November 22, 1997.

20. Phillip Warren Miller, Greater

Jacksonville's Response to the Land Boom of the 1920s, MA thesis, University of

North Florida, 1989, pp. 91-92, 119ff. We get a glimpse of housing costs in 1915

from "Estimates

of a Bungalow in Florida," The National Builder, March, 1915,

pps. 69-72 as being $2206.04. In 2005 dollars, this was $42,634.77.

The configuration of such a house is unknown.

21 Bill Foley, "Millennium Moment: February 9,

1925," Florida Times-Union; Johnston, Architectural Resources,

p. 58.

<< 2: Pablo Beach, 1886-1907 || 4: The World's Finest Beach, 1925-45 >>

|