|

1: The Setting

About the Author || 2: Pablo Beach, 1886-1907 >>

Figure 1-1 The Ocean

The cold, bitter wind swept from the ocean across the "world's finest beach"

westward to the marshes and San Pablo Creek. The nor'easter, as northeast winds

were called, was not only cold but destructive. As the wind whipped the waves into a frenzy, they crashed against the shore, shifting the loose sand. The winds formed or destroyed

dunes, for they are sculptors. Sea oats anchored much of the sand but it shifted. The coast

altered a bit; the wind and the ocean unknowingly cooperate, but what they do

works.

Nor'easters never lasted long, two or three days usually; most days there was just a breeze. Some mornings, the ocean was smooth as glass with small waves rolling ashore. Some evenings too. Sandpipers scurried across the beach. Sea gulls flew to the beach in the morning and inland to roost at night. The occasional pelican would skim above the water and suddenly dive bomb when it spotted a meal. Porpoise schools would move along the coast, breaking to the surface for air. Underneath the surface and away from the breakers, various fish swam, eating and being eaten. Jellyfish and Portuguese men-of-war lived beyond the breakers but storms sometimes blew them ashore, where they died.

Figure 1-2 Calm Ocean

Or the surf could be rough, either morning or evening or all day in

stormy weather. When it did, even the marshes and San Pablo Creek might ripple. The Creek, a river by most standards, ebbed and flowed with the tide which changed about every six hours for its mouth was the mighty St. Johns River, itself a tidal river. Birds

took refuge there. So did alligators, snakes, turtles, panthers, bears, and

assorted other wildlife. The water and the marshes were a wonderful habitat.

So much water. The Atlantic Ocean to the east; marshes and the San Pablo Creek to the west; the St. Johns River to the north; and marshes, swamps, scrub land, the Tomolato River down to the St. Augustine Inlet to the south. A barrier island as it were, sitting on the northeast Florida coast adjacent to what would become Jacksonville, Florida.

For centuries isolated to all but the hardy.

An island of sand and dirt, of marshes, swamps, and dry land, of palmettos, yucca plants, cabbage palms, pine trees, and live oaks. Wildlife of all kinds loved it-birds, panthers, rabbits, rats, alligators, crab, snakes, frogs, squirrels, wolves, deer, fish, and others. Mosquitoes-millions and millions of them-and gnats and sand fleas, food for birds but so difficult for humans. The pungency of the marsh would tell people that they were approaching the coast; to those who lived on the

Beaches, it was the smell of coming home; to those who lived farther inland, it was offensive.

It was hot and humid for much of the year. Temperatures reach the low-90s in the summer, mitigated by the sea breeze, but are mild in winter, except those rare occasions when it drops below freezing. The rains come, over 50 inches a year, sometimes as early afternoon showers, others as downpours for a day or more. The climate is subtropical.

Cockroaches did not die. There were cold winter days--it even froze on

occasion--but not many and not for long. People in New England might think it

was summer. Until the advent of cheap air conditioning, not many humans liked

the weather.

Who would want to live there? If any did, it was not many.

People migrated to the Great Plains but avoided northeast Florida.

Humans first migrated into the region thousands of years ago and would continue.

The Timuqua/Timucua arrived 12,000 to 16,000 years ago. We have no way of

knowing how many people lived in the region before the Europeans started

arriving. Some scholars have 14,300 but they were guessing.1

There was no census. Glenn Emery, who ran a Web site entitled

jacksonvillestory.com, says "Downtown Jacksonville was the location of a grand Timucua city

called Ossachite. It proved bigger than other communities in the area.

Ossachite thrived about 1000 years ago, but it survived until about 300 years ago."2

The Timuqua (Timucua), as they are known, would have found plenty of game and ample fishing spots so an

appreciable number could have lived on or near the island. Europeans reported some people on the

northern part of the island but not many.3 James Mooney in The Catholic Encyclopedia distinguishes among three groups of people:

The tribes forming the Timucua group proper centred chiefly along the St. John's River, the principal being the Timucua along the upper part of the river and about the present St. Augustine, whose chief, known to the French as Outina, had his settlement about the present Welaka, and ruled some forty villages, with perhaps 6000 souls. On the lower course of the river were the Satuniba, the enemies of the Timucua and nearly as numerous, and west of them, toward the Suwanee River, were the Potano,

with over a thousand warriors or perhaps four thousand souls. Several other tribes

were of minor importance.4

It seems that many writers use the term "Timucua" generically. Dr. Jerald T. Milanich says "The Timucuas ruled by Chief Saturiwa lived east of the St. Johns River in Florida and south

Georgia."5

Figure 1-3 The Jacksonville Area

Regardless, Europeans and their diseases would destroy the Timucua. There were not many foreigners at first but they brought millions of microbes and viri. Europeans would not kill as many Timucua as would their diseases to which the Timucua had no resistance. Not that Europeans wanted to destroy the natives. To the contrary, they wanted servants, slaves, ands sexual partners while they sought ways to get rich with as littler work as possible.

Huguenots, French Protestants, under the leadership of Jean Ribault sailed into the St. Johns River (the French called it River of May) on May 5, 1562 and established an outpost on an island, calling it Mayport. They met Chief Saturiwa and his people. They exchanged presents, food on the part of the Timucua. Ribault returned to Europe and was delayed in his return to Florida when he was imprisoned. René Goulaine de Laudonnière brought a large expedition and created Ft .Caroline on the south shore of the river and further west on June 30, 1564.

The Timucua were helpful to the French until Laudonniere made a treaty with their enemies, Timucua west of the river. Then they turned against the French, who stole food and kidnapped a Timucua chief. Besides Frenchmen brewing trouble with the locals, Spain was planning to expel the Huguenots. Knowing that Laudonnière was a terrible leader, the French Crown sent Ribault back to Florida, but the French could not hold Fort Caroline. When Pedro Menéndez de Aviles attacked Fort Caroline in August-September, 1565, the Saturiwa Timucua joined him. Knowing that the French would have ships guarding the mouth of the river, Menéndez sent troops overland through marshes and scrub to attack from the land side. They and their Timucua allies killed almost 150 settlers. Others escaped. Menéndez renamed the fort as San Mateo.

When Ribault tried to attack from south of Saint Augustine, Menéndez captured and executed them. He established a fort, Matanzas, to protect the southern approach to the main fort in St. Augustine, the Castillo de San

Marcos.6

Helping the Spanish expel the French was Phyrric for the Spanish destroyed them. Eventually, disease reduced the Timucua population. Those who survived became more Hispanisized and many worked for the Spanish around St. Augustine. The Timucua died out. When the Spanish pulled out of St. Augustine in 1763, they took the last 12 with them to Cuba. The very last Timucua, Juan Alonso Cabale, died in 1767, as did Timucua culture. We can not even trust the drawings of them done by Jacques le Moyne because most that remain were done from memory and then engraved by someone else. Renegades from Georgia, Creeks, slowly migrated into the area but not many of

them.7

Florida was a backwater of the Spanish empire, held because it was part of the defense system not because it had precious metals or sedentary populations they could put to work. It could not support itself. St. Augustine was a naval base to protect the Spanish fleet, its population subsidized by a Crown grant, the situado. Other forts, like Matanzas south of St. Augustine, protected the base. Scattered other forts in Florida similarly were defensive. The New World Empire was so vast that Spain could not protect all of it so the Crown concentrated on the most important parts-Mexico, Peru, Cuba-and adopted a defensive strategy of presidios, forts, and missions. Throughout the empire it relied on the conservatism of the population, that they would be loyal to the Crown and the Church. To populate is to govern.

The Beaches area was sparsely populated in this Spanish era. In the second half of the 17th century and into the eighteenth century, the Spanish Crown granted land to encourage

settlement.8 Diego Sinoza had a plantation in what is now Palm Valley in northern St. Johns county. Few people lived on it and, fortified and sometimes referred to as Fort San Diego, it was captured by James Oglethorpe on May 12, 1740. After he failed to capture St. Augustine and withdrew back to Georgia, Diego got his property back. There simply were not enough people in the area.

Anglos would destroy any hope of holding Florida and would do it in two stages. The first came when the British Crown acquired Florida as spoils from the French and Indian War

(1754-63)in exchange for Cuba which had acquired during the war.9

Florida was contiguous with Georgia and Alabama. Possessing it not only secured the east coast but also stopped runaway slaves and criminals from escaping into Spain (that is, Florida).

The English changed things so as to encourage people to come. To administer the new lands better, the Crown created two

colonies—West Florida with its capital in Pensacola and East Florida with its capital in St. Augustine. Since thousands of Spaniards left when the British took over, the British allowed slavery (the Spanish forbade it) and facilitated the creation of plantations. Some of these were along the St. Johns River, Pablo Creek, and on the coast. To tie Georgia and East Florida together, the King's Road or Highway was built from St. Augustine through Cowford into south Georgia between 1767 and

1772.10

The Crown was successful because these conservative colonies did not join their liberal and radical brethren to the north in the American Revolution. Instead, they harbored loyalists. Like the other British North American colonies-Lower Canada, Upper Canada, Bermuda, the

Bahamas—they saw nothing to gain by participating in leftist politics.11

They backed the wrong horse. Great Britain lost the war and the victors reaped

the spoils; Spain, an ally of the American revolutionists, took Florida back.

Spain had to deal with the largely Anglo and African population which had come

to Florida during the British period.

The Spanish Crown honored British land grants and continued

most of what the British had done but doing so backfired. Whereas Spain hoped

patriots would settle in the Floridas, replacing the thousands who had left in

1764-64, such was not to be the case. People from Spain or its possessions were

not going to emigrate to Florida but people from the United States would and

did. The Crown required that they swear allegiance. Some did. Some did not.12

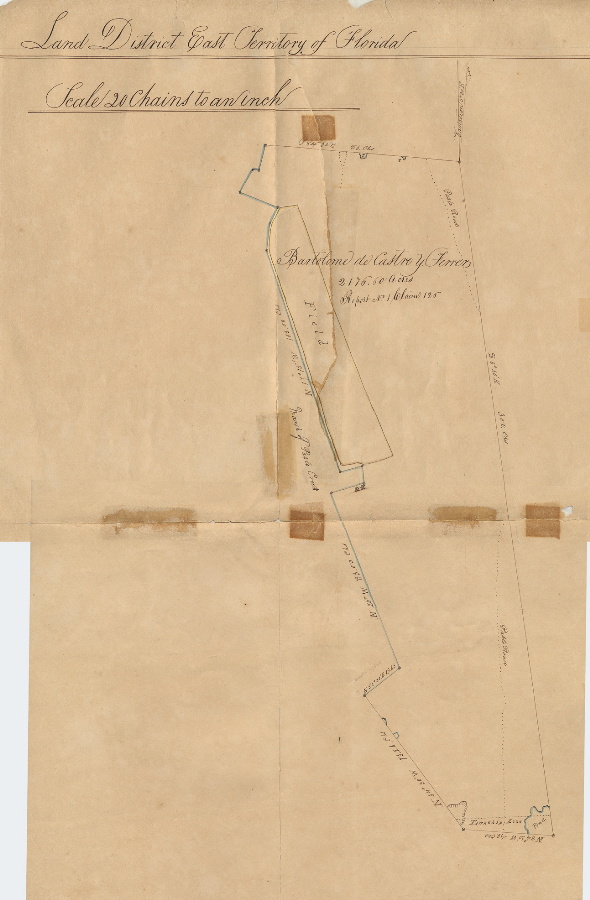

Much of what became the Beaches was part of three land grants.

The largest was the Bartolomé de Castro y Ferrer grant. Castro y Ferrer bought

the grant from John McQueen in 1804 for $7,000, half down, half in 1807.

San Pablo was about 2,000 acres east of Pablo Creek. Both had to swear that

they were loyal to the Spanish Crown before the transaction was allowed.

Castro y Ferrer proved that he had served the king. Castro y Ferrer would obtain additional lands.13 Bartolomé de Castro y Ferrer

had another 1,000 around Little Creek he obtained in 1815.

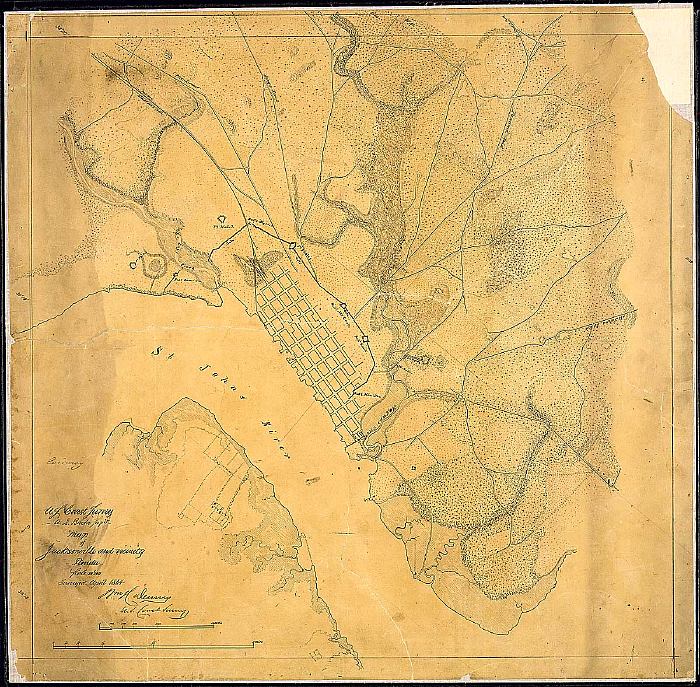

Figure 1-4 Bartolomé de Castro y Ferrer Grant

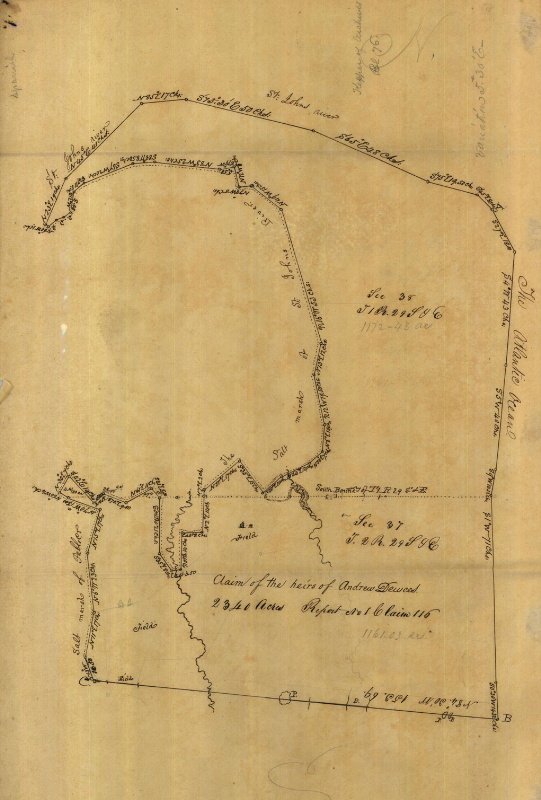

The Andrew Dewees grant, acquired in 1790, was also large,

about 2,900 acres. His plantation, Naranfil or Orange Grove, was south of the St. Johns River and east of Pablo Creek and abutted the John McQueen-Castro y Ferrer

grant.14

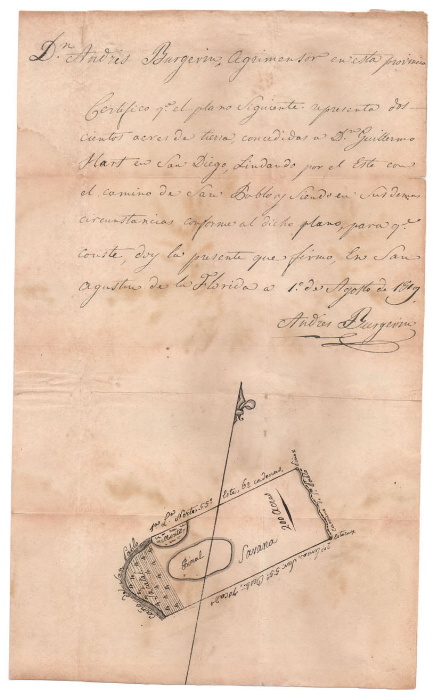

Much smaller was the William Hart grant of 200 acres on the San Pablo Plain.

Figure 1-5 Andrew Deweese Grant

Figure 1-6 William Hart Grant

Although these late 18th century grants brought some

settlement to the Beaches area, it could not have been much. Sand and marshes

are not conducive to agriculture or animal husbandry. We do not know how many

people lived at what is now the Beaches. We do know about Jacksonville, however.15

Humans settled in Jacksonville long before 1763 when the British settled Wacca Pilatka (as the natives called it and the British, Cowford), because the St. Johns River narrowed there enough for cows to ford the river near Fort San Nicolas on the south bank. Unhappy with Spanish rule, some colonists of English and African extraction revolted and declared the "Republic of Florida, destroying the Fort, gaining control of the land between the St. Mary's River, the present border with Georgia, and the St. Johns River. They captured the important smuggling and fishing port of Fernandina. The republic was squashed but the Spanish fully regained control. Florida entered the United States as a territory when Spain finally ratified the Adams-Onís treaty of 1819. In 1821, the people of Cowford, under the influence of Isaiah Hart, laid out Jacksonville. There were only approximately 250 people in the town, south across the river in San Nicholas, and other settlements

nearby; the next year, residents laid out Jacksonville, naming their small village after the first territorial governor, Andrew Jackson. A decade later, in 1832, they obtained a city charter from the state.16

Jacksonville remained small for decades because there was

little to attract people to settle. Getting there was difficult, but, it did

have trade a long-standing in lumber, naval stores, and livestock. It also

was a small resort for invalids. There was little to draw people there. Many

citizens resisted change. Few lived there when statehood became an issue in

1845. The statehood vote in Duval County (bigger than Jacksonville) in 1845

was 174 against and only 31 for. Thus, there were only 205 "white" males in the

country and fewer, therefore, in the city!17

Davis estimates that there were 250 people there in 1835. By 1850, Jacksonville

contained only 1,045; by 1860, 2,118.

These figures did not include "suburbs" like South Jacksonville. As Johnston

notes, "nearly all of the oceanfront property in what became Atlantic Beach,

Jacksonville Beach, and Neptune Beach became public domain in the 1830s and

remained public lands until the late nineteenth century."_18

Hazard, as Mayport was originally called, with its location

on the St. Johns River a few miles west of the mouth of the river, was more

important in the early days. In 1864, there were about 600 people there. One

could earn a living by fishing, transshipping cargo to Jacksonville or south,

taking passengers to Jacksonville, or as an entrepôt for mail to Jacksonville

or the people in what became the Beaches. For example, in 1830-34, a mail route

went from Mayport through Pablo Beach. When lumbering became important, the

village's name was changed to Mayport Mills in 1849. The shipping of timber

and naval stores became important enough that a lighthouse was built in 1859

to help ocean-going-ships find the river mouth and be warned of the sandbar

there which made navigation tricky.19

Figure 1-7 Mayport Ad

Mayport and the Jacksonville area played a minor roles in the

Civil War. In 1862, the Confederates built Fort Steele at Mayport for the

Jacksonville Light Infantry.20 The Duval County

Cow Boys went to St. Johns Bluff but the United States Army occupied Jacksonville

on March 12, 1862 for a month and then left but came back in October. The United

States Navy maintained a blockade of the lower St. Johns with a squadron at

Mayport Mills. Four miles upstream, the Confederates fortified St. Johns Bluff

and the United States could not dislodge them during the September 10-11, 1862

battle between the Confederate shore batteries and US ships. After the US Army

began invading the Bluff from the land was victory assured on October 3. The US

Army ten occupied Jacksonville.21

The major land engagement was the Battle of Olustee near Lake City west of Jacksonville which US Army lost on February 20, 1864. They retreated back to the town.

Edwin C. Bearss notes that Mayport played a minor role in the Civil War.22

General Thomas W. Higginson noted that

"Jacksonville, on the St. John's River, in Florida, had been already twice taken and twice evacuated; having been occupied by Brigadier-General Wright, in March, 1862, and by Brigadier-General Brannan, in October of the same year. The second evacuation was by Major-General Hunter's own order, on the avowed ground that a garrison of five thousand was needed to hold the place, and that this force could not be spared. The present proposition was to take and hold it with a brigade of less than a thousand men, carrying, however, arms and uniforms for twice that number, and a month's rations."23

So Higginson, commanding the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry, was sent to occupy Jacksonville in 1863.

"The claim was, that there were fewer rebel troops in the Department than formerly, and that the St. Mary's expedition had shown the advantage possessed by colored troops, in local knowledge, and in the confidence of the loyal blacks. It was also urged, that it was worth while to risk something, in the effort to hold Florida, and perhaps bring it back into the Union."24

Figure

1-8 Jacksonville in 1864

The Civil War years made a difference in population growth for Jacksonville. The city grew 326% in 1860s to 6,912 persons. Of these, 3,989 (57.7%) were African-American whereas the African-American population in 1860 was only 46.5% or 985 persons. Free "blacks" went to the Jacksonville area after the war, drawn by the U.S. Army and the Freedman's Bureau. Ex-Confederates came back. Northern investors saw a wonderful opportunity. Lumber mills, naval stores, fishing, and farming picked up. Tourism began playing a very important role in the city's economy.25

Jacksonville's population would skyrocket in the 1880s and grow substantially in the 1890s after the sluggish 1870s when it only grew to 7,650 in 1880. One reason was the Disston Purchase in 1881 which stimulated investment in railroads. The Florida Internal Improvement Fund owned title to millions of acres of land but was deeply in debt. Until the debt was paid, the state government could do nothing. Hamilton Disston bought four million acres for a million dollars, clearing the debt. With that the state began subsidizing private railroad companies with grants of land. By 1890, it was 17,201, an increase of 225%. By 1900, it had increased another 165% to 28,429.

Industrialization not only resumed after the War but the pace increased substantially. The expansion of the railroad network made it easier and cheaper to move freight and people. The first railroad was the Florida, Atlantic, and Gulf Central; chartered in 1851, it reached Baldwin in 1859 and Alligator (Lake City) in 1860. It connected to the Florida Railroad which ran from Fernandina on the northeastern coast to Cedar Key on the Gulf of Mexico. A line coming into Live Oak from Georgia was connected to the Florida, Atlantic, and Gulf Central. Then a boom began in the 1880s. Henry B. Plant built the Savannah, Florida, and Western and brought it into Jacksonville. Plant's railroads became the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad. Henry D. Flagler took over the Jacksonville, St. Augustine, and Halifax Railroad, other small railroads, eventually melding them into the Florida East Coast Railway. Flagler spanned the St. Johns River between Jacksonville and South Jacksonville with a railroad bridge. The Seaboard and Southern were built and went through Jacksonville. Thus, most people and freight going to and from central and southern Florida passed through Jacksonville.26

Equally important were measures to develop Jacksonville as a port, for goods shipped by land often came by sea. The building of jetties, begun in 1879 with U.S. government monies made it

possible for larger ships to sail the twenty miles upriver to Jacksonville. In the 1890s, Duval County expended the vast sum of $300,000 to dredge an 18-foot channel.

A lighthouse was important both the help ships in the entrance as well as to warn them of hazards. The first lighthouse was built in 1830 but demolished in 1835 and replaced because it could not withstand the weather and tides. That was replaced in 1859 because wind-swept sand dunes were covering it; the new one was sixty-five feet high. Its height was increased by fifteen feet in 1887 and the lighthouse was used until 1929 when a light ship took over its function.27

As the United States grew more prosperous, there were more

wealthy people who had the money and leisure to travel and Florida was a

destination. Jacksonville was

the major Florida tourist destination until Henry D. Flagler built

the Florida East Coast Railroad to more southern (and warmer in winter) parts.

One could get there by railroad, a big plus since what roads existed were

terrible. Once there, one could also take cruises up the St. Johns to the south

and also on the Oklawaha River. Even after tourism shifted further south,

Jacksonville prospered as a gateway city.

The Beaches developed because Jacksonville developed, but good

transportation had to exist first. Railroads made the difference. In October,1883,

a contract was let for the Jacksonville and Atlantic Railroad which would

operate between South Jacksonville and Pablo Beach. There was ferry service

across the St. Johns between Jacksonville and South Jacksonville. On November 12,

1884, even before the railroad was completed, lots were sold where Jacksonville

Beach now is. In order to maximize profits, the lots were quite small, often

50 feet by 100 feet.28 The Jacksonville &

Atlantic Railway Company built a narrow-gauge road of three-feet gauge and

35-pound rail which was completed in December, 1884. On November 12, 1884,

before the railroad was finished, the company, which had land at the beach,

34 lots for a total of $7,514. This was the first development. The station at

the beach was attached to the rear of the Murray Hall Hotel.29

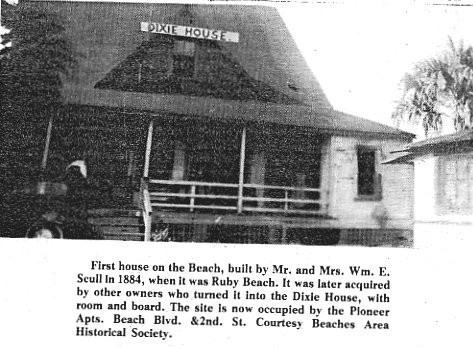

The settlement of tents called Ruby Beach was named after

the baby daughter of William E. and Eleanor K. Scull, who moved there and

lived in one tent while using another tent as a general store and post office

for the once-a-week mail. Eleanor Scull, born in 1861 and who was 78 when

interviewed in 1939, ran a rooming house for tourists in Jacksonville, her

family having moved to Florida from Indiana. She married William Scull in 1879.

Her father, D. H. Kennedy, had helped survey the railroad route to the beach,

so she and her husband were familiar with the beach. They moved there in

October, 1884. The Sculls got the post office concession and named it

after their daughter Ruby. William Scull got the mail at Mayport and

brought it south over the hard-packed beach sand at low tide in a wagon.

They built a house in 1885 from lumber they salvaged from a shipwreck near

Mayport which was carrying it as cargo. Since there were no roads, they brought

it down Pablo Creek and then the few miles overland to where the Pablo A

venue area is now. When the train finally reached the beach, there may have been thirty families living in Ruby Beach.30

Thanks to the New Deal, we have access to the memories of Eleanor Scull:

From the time we went to the beach in October, 1884, until February, 1885, we

were the only family there. Then a family built a small house and located in

the woods about a mile south. Another family lived at what is now Neptune Beach,

two miles north.

When we first went to the beach it took two hours to drive to the boat landing at

Mayport and three more to make the trip to Jacksonville up the St. Johns River.

The steamboat bringing mail and supplies from Jacksonville at that time was the

Katy Spencer in charge of Captain Napoleon Broward, afterwards governor of Florida.

There was a way by which Mr. Scull used to drive to Jacksonville by going six miles

south through the Palm Valley section where there was a settlement, but it took

two days to make the trip, so that one night he had to camp out. There was no

way to cross Pablo Creek except to ford it, and that was the reason they had to

go such a roundabout way in order to reach near the source of the stream where

it was narrow and shallow. Dr. Burroughs had an orange grove in the Palm Valley

section, and he used to drive that route too, and sometimes he and Mr. Scull

would make the trip together. There is still quite a bit of ocean front between

Jacksonville and St. Augustine which has been slow in developing.

The second house at the beach was built by Mr. and Mrs. Dickerson. They had

a store and she was afterwards postmistress. In September, 1886, the post

office was moved to the Murray Hall Hotel, and Mr. French, who was the manager,

acted as postmaster. This arrangement was not satisfactory. The guests at the

hotel objected to the riff-raff then at the beach coming into this splendid

hotel for mail, Mr. French thought it took up too much of his time, and the

people themselves did not like the arrangement. After the hotel burned, it was established in a store up town.

I forgot to say, the railroad company built a pavilion at the terminus in the first period, and

it had a skating rink which was quite popular, both with the excursionists

and the people at the hotel and the beach residents.31

Figure 1-9

Ruby Beach attracted rich and somewhat eccentric people.

General Francis E. Spinner, ex-Congressman and Treasurer of the United States

appointed by Abraham Lincoln and also serving under Andrew Johnson and U.S.

Grant, moved from Jacksonville to the beach. He created a compound he called

Ruby Camp Caroline and his friends and acquaintances joined him. His compound

included a pavilion with a honky-tonk.32

Prominent businessmen in Jacksonville began building summer cottages there.

Ruby Scull's fame as the namesake of the settlement, for the railroad company decided it was to be Pablo Beach in 1886. However, serious development had finally begun south of the port and fishing village of Mayport.

____________

Endnotes

1.T. Frederick Davis, History of Jacksonville Florida

and Vicinity 1513 to 1924 . (Jacksonville, 1925), p. 2.

2.In Timucua

Ossachite but other sources say there were few left by 1700. Emery has

information at Timucua

Times.

3.Haines Brown has a brief essay entitled "A

brief history of the Timucua people of Northern Florida".

4. "Timucua Indians," Catholic

Encyclopedia. 1907.

5.Taino-L, May 21, 2000 archived at "The

Timucua Indians-After the Europeans Came-(1562-1767), " ,

6. Davis, p. 4. Francis Parkman did a very readable Huguenots

in Florida: the Pioneers of France in Florida.

7.There are many accounts of Jean Ribault, the Huguenots, and

the St Johns River. An easily accessible one is by M. Adele Francis Gorman,

"Jean

Ribault's Colonies in Florida," Florida Historical Quarterly

44:1 & 2.

8. Sidney Johnston, The Historic Architectural Resources of

the Beaches Area: A Study of Atlantic Beach, Jacksonville Beach, and Neptune

Beach, Florida. Jacksonville, FL: Environmental Services, Inc., July, 2003), p.

10. ESI Report of Investigations No. 382. Prepared for the Beaches Area

Historical Society. Hereafter cited as Johnston, Architectural Resources.

9. Seven Years War, 1756-63, in European history.

10. New

World in a State of Nature; British Plantations and Farms on the St. Johns

River, East Florida, 1763-1784 ; Johnston, Architectural Resources, p.13.

11. Michael Gannon, Florida, A Short History.

Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1993, pp. 18-24 does a quick synopsis

of the English period.

12.Gannon, Florida, A Short History, pp. 24-27.

13. Florida

Memory, Spanish Land Grants, Confirmed. John McQueen deed for plantation known

as San Pablo to Castro y Ferrer. There is a description at Box: 7, Folder 7,

Page 9 of the site. The plantation was east of Pablo Creek. Another document

that says 2,000 acres on the west side of Pablo Creek in addition. He got it

free in 1818 for 24 years of service to the King. He acquired another 35 acres

in 1817.

14. Andrew

Dewees Grant . In 1804, the Dewees plantation was called the Orange Grove or

Naranfil, some 2290 acres/2300. In 1882, some of this grant was subdivided and

given to three heirs, the Floyd family being one of them. The Floyd family

became one of the mainstays of Mayport. The grant included Mayport. St Johns,

Atlantic Ocean, Pablo Creek, and south of section 9 and parts of 5 & 6. It

was resurveyed several times. The 1882 survey excluded Mayport and extended it

further south but 1885 appeal reversed this. William Hart had 200 acres in the

San Pablo Plain in 1809 and was confirmed 1816. See www.floridamemory.com.

15. Land grants are discussed in Johnston, Architectural Resources,

pp. 17-22.

16. Carita Doggett Corse, Story

of Jacksonville. 1935. She was the sister of Frank E. Doggett

(1906-2002), principal of Duncan U. Fletcher Junior-Senior High School from its

beginning in 1937 until 1969.

17. Sharon

Weightman, "Cowford grew on the river's edge."

Florida Times-Union. February, 1998.

18.Davis, p. 75; Johnston, Architectural Resources, p. 34. South Jacksonville did not

become incorporated into Jacksonville until 1932.

19.Michael Gannon, A Short History, p. 31 says Mayport

was created in the 1820s and 1830s.

20.City of Jacksonville, "Mayport

Naval Station".

21.T. Frederick Davis, "Engagements at St. Johns Bluff

St. Johns River, September-October, 1862," Florida Historical Quarterly,

15:2 , pp. 78-85.

22.Edwin C. Bearss, "Military Operations On The St.

Johns, September-October, 1862 (Part I)," Florida Historical Quarterly,

42:3 (January 1964 ), 232-248. and See Edwin C. Bearss, "Military

Operations On The St. Johns, September-October, 1862 (Part II)," Florida

Historical Quarterly, 42:4 (April 1964 ),331-351.

23. Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. Army Life in a Black Regiment.

Historical Text Archive. Chapter 4.

24. Ibid.

25. Campbell Gibson and Kay Jung, "Historical

Census Statistics On Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic

Origin, 1970 to 1990, For Large Cities And Other Urban Places In The United

States.

26. Herbert J. Doherty, "Jacksonville As A

Nineteenth-Century Railroad Center," Florida Historical Quarterly

58:4 (April, 1980 ), 374-387.

27. St. Johns River Lighthouse.

28. George W. Simons, Jr., Report for Jacksonville Beaches

Chamber of Commerce, 1944, p.10 comments on the very small lots in

Pablo/Jacksonville Beach. Davis, p. 350, write of the railroad and real estate.

29. Davis, p.169.

30. Johnston, Architectural Resources, p. 39.

31. Rose Shepherd, Interview

of April 11, 1939 with Mrs. E. Scull, American Life Histories: Manuscripts

from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936-1940.

32. Bill Foley, "Disgust With Big-City Rat Race Gave the

Beaches Life in the 1880s," Florida Times-Union, August 20, 1997.

About the Author || 2: Pablo Beach, 1886-1907 >>

|