12: Build-up of the operating staff

<< 11: Construction by Government || 13: Accounting >>

Once all the planning had been done, orders placed, and construction was well in hand, came the

need to bring in staff and employees for training to operate the service, on and after opening day. In

our so-called "Bull sessions," we had quickly recognised that introducing an intensive commuter

service would require additional personnel, both to administer and to operate. There were so many

other things being organised, work being in hand, that it was not until May 1966, that I was able to

make a first attempt at creating an organigram. I did this work on my dining room table, at 4.00

AM on a Sunday morning, That gave us all something to work with, and discuss with the Personnel

Department at area and regional levels. The urgency was that it would quickly be necessary to

bring in supervisory staff, to follow the advancement of the construction work, to prepare the

operating manuals, design the training courses for the employees who would do the operating, then

do the training in time for opening day.

With the pressures on the railway from all the growing traffic, and the

re-organizing being made

for the opening of the new hump yard, all available qualified supervisors were fully occupied.

More supervisors would need to be trained, and given enough experience to be able to do the job.

More than that, the commuter service would introduce many practices new to the railway, so the

supervisors who would join us should be experienced already in railway work so that they would

understand how the existing practices would be affected. Drawing them from other jobs would

leave gaps somewhere else. I had demonstrated what would be our need, but it fell to the

Operations Manager to find the candidates for us, then organise replacements where they would be

coming from.

Throughout the Summer, the staffing requirements from the organigram and where to draw

them from were discussed and refined. Personnel were transferred in as needed, even before

everything was agreed. The final version of our organigram was approved at a general meeting

with the Operations Manager and all of the area operating staff on October 6th 1966. That left us

seven months to find them all, and build us up to an operating organisation.

For the commuter group, the first staffs needed were for the train equipment. The locomotives

were to come out of General Motors, London, much earlier than needed for the commuter service,

but we would need staff to look after them as soon as they were ready for inspection and testing

there. Next would be deliveries of the car equipment from Hawker-Siddeley in Thunder Bay, so

more staff from the Equipment Department traveled to the plant to run tests out on line, before

bringing them to Toronto. This would be the first time we could have engine and train crews to get

the feel of operating the new equipment. Then would be staff to operate the ticket booths and ticket

stock rooms, and the accountants to accumulate the expenses, and prepare the bills and statistical

returns to the Government.

For the Government, supervision of parking lots and access roadways became necessary, then

organisation for snow clearance ready for winter conditions. They had an interest also in observing

the quality of the service they had contracted for with CN.

The locomotives

Eight locomotives were under construction in London, mixed in with their longer production

line. They were ready for delivery in the fall of 1966, except that the auxiliary engine-generators

for head-end power could not be ready until Spring of 1967. However, CN had need of additional

motive power for hauling the growing freight traffic, so delivery of the units was accepted as they

became ready, and were rented to CN throughout the winter, and used on freight trains between

Montreal and Toronto.

It was basic routine for CN to inspect units under construction, by inspectors in the

manufacturer's plant, so no special arrangements were needed for that. But the GO-Transit image

called for the cabs of the units to be white, when they would be hauling the commuter trains, and

there was some concern that the paint should not deteriorate in freight usage. So in that first

Winter, the units were delivered and operated, painted overall in dark blue.

When I visited the GO-Transit offices for an interview with Joe Desjardins, who was then

Director of Customer Services, he had with him Tom Henry, also on his staff. In the year when the

locomotives were being used on freight trains, Tom was a reporter for The Mississauga News. Tom

told me the story of his problems with the colour blue, while he was taking photographs to use with

his reports. "The units were being delivered in the Fall of 1966. They came out of GM without the

auxiliary engine-generators, but with a slab of concrete for weight, and painted a dark blue. It was a

real challenge to me to take photographs so that they did not come out black. I wanted them to

come out looking blue".

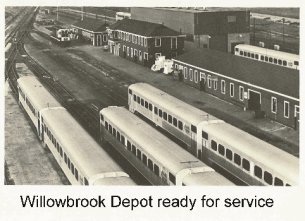

Staffing Willowbrook

Since train equipment was the first to come, this was where we needed operating staff the

earliest. Bob Withrow had been involved with the equipment even before we had created the

commuter group, so he had followed the locomotives and cars from their first ordering. Now there

was need to recruit staff to maintain the equipment at the Willowbrook depot. Assigning staff in the

Equipment Department fell to the responsibility of Dick Babb, the Superintendent of Equipment for

the Toronto Area. Dick sent Bob Withrow to Montreal to interview a candidate he had selected.

When Bob had explained that the job would be as General Forman, setting up a completely new

depot operation, that candidate rose immediately to the challenge. He was Doug Young, then

General Forman of the electric shop at Point St. Charles, in Montreal. He reported to Bob Withrow

in Toronto on August 1st, 1966, about ten months before we started the service. With him he

brought Ron Simpson as Second in Command.

I met with Doug at his home in

Orangeville, Ontario, where he mows his big

lawn on his power mower! He told me the

story of his first visit to Willowbrook, with

Ron at his side. Together they went out to

inspect the site, and he told me what

happened. "The day we went on that

property for the first time, to start planning

how it would operate, we walked in along

the shop track, beside the old car department

buildings. There was a box car with

equipment of some type in it, chains, cables

or whatever. I smelled smoke, and stopped to

say to Ron that there was something burning.

He looked around and saw that the boxcar was on fire! There was a caretaker in the area, so we

asked where we should run to find a phone. We called the fire department, which came to put the

fire out. Then Ron and I looked at each other, wondering whether this was something we might

expect at Willowbrook. We've only just arrived, and here we are putting out fires already!"

"Almost as soon as I came on the job, you sent two of us, Don McEllistrum and me, over to

England, to observe the manufacture of the diesel engines that Hawker-Siddeley would install on

the self-propelled cars. We were not at all knowledgeable in this model of engine, so we learned a

lot in a short time."

As we grew closer to the date of inauguration, the commuter group brought in two road

vehicles, an automobile for our on-line Supervisors to use, that we called on the radio "Mobile

one", and a mechanical repair vehicle, called "Mobile Two". I asked Doug what he remembered

about getting "Mobile two" ready for service.

"I remember in England we visited a locomotive shop, attached to a commuter operation, to

meet with their supervisors and gain some knowledge of problems and solutions they had acquired

from experience. They had road trucks, equipped with tools and spare parts that the shop could

send out quickly to any site where a train might have developed a mechanical problem. So when

we returned to Toronto, I controlled the selection of equipment to be carried on our truck."

"When I came to join you, you used to sit us all down together, Bob Withrow, George Dollis,

Jack George and the other good people, in what I would call "bull sessions", just talking about how

we would run GO-Transit. So we had input from everybody. It was not a fait accompli. It was a

case of building it up from there. That is where I got my impressions and my education"

Did you have any feeling that something different was happening, different from the way other

operations had been running?

"Different? Oh, yes. We were planning to put together a shop where the locomotive people and

the car people would be working together. There had always been a rivalry between them. Some of

it was well intentioned, but to some it was real. At Willowbrook, the locomotives and cars would

be parked coupled together in one train for servicing, unless they had to be separated for work. I

wouldn't suggest for one minute that there were no animosities. There were. But I think we got it to

work very well."

The train equipment

Did you go out to Thunder Bay to while the cars were being built and the trains were out on line

for testing?

"I spent a lot of time there, as also did Bob Withrow. We had support from people who went out

from the Equipment Departments of the Region and Headquarters, for the quality control and

testing. The designs of the cars were completely new to us. We assigned two of our supervisors,

Bill Adams and Roy Thompson, as our representatives on the quality control team. They worked

closely with Norm Custer, in charge of the manufacture in the Hawker-Siddeley plant."

"We had one tense situation. It was raining hard, when we had taken a train out of the plant for

test runs along the line. When we brought the train back, it was late, and someone had closed and

locked the gate we had to drive through to put the train back into the plant. We were drowned,

absolutely drowned, and there was no telephone around. Finally we got to a phone, and at last

someone came to resolve the whole thing. I'm sure they'll remember the guy with the red face, who

was mad as all get out!"

How familiar was your staff with the idea of Push-pull, with control wires running through all

the coaches?

I don't think anyone in Toronto was familiar with it. Both Transportation and Equipment had

that situation to contend with. To change ends, different valves and switches had to be opened or

closed, so there were growing pains. Sometimes trainees would cut out the wrong things, then we

would give them more training."

We had the craziest problem with the cars after we had them in our hands. The door control

panels required a key to activate them when the Conductor moved to operate from that position.

Every coach had one door with a panel above it on each side of the car. We were supposed to

receive one key with every car, but in fact we received only two keys! We asked Hawker-Siddeley

for the keys that we were supposed to receive, but got the response that there were no more keys

available, and if we wanted more, we would have to buy them. They quoted us a price that was out

of this world for just door keys, but we were in a bind.

We had to have enough keys to be able to send out four

trains, and more for crew training and equipment testing.

The shop found a small number of keys that could be

modified to fit the door control panels. This was barely

sufficient, so George Dollis and Harry Dykstra went out

to visit locksmiths in the city to find keys that could be

modified to fit. George found some, with very long

handles, but they would do, so we ordered them to be

modified for us. I remember the moment when Harry

returned from the locksmith and placed on my desk a

bundle wrapped in newspaper, that he opened up to show 100 keys! What a relief! Another panic

over!

Supervision of train crews.

For getting staffs ready for test operations when the train equipment could come out of the shop,

we would need to train some crews ready to take them out on line. Supervision of train crews is

handled by Trainmasters. These people are the first line supervision, qualified to give direction and

training to train crews in the work they have to do, the way they handle their trains, and the

technique for doing it. So we needed to bring Trainmasters on staff ahead of the trains being ready.

The organigram I had drawn up, called for three Trainmasters. Not all of them would be needed

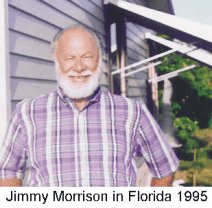

in the beginning, so our first Trainmaster was Jimmy Morrison, who came on the job with us.

I caught up with Jimmy and his wife Miriam, at their winter retreat down in Florida. Jimmy told

me the short story of how he came to work with us in the first place. As a Supervisor around Union

Station, he was deeply into the complications of planning and supervising the movements of the

extra passenger trains during of the Xmas season. For this work he answered to Roy Menary, the

Operations Manager on the Toronto Area. Quite unexpectedly, on 2nd of January, he was told to

report to Roy Menary's office, so he immediately wondered where he might have gone wrong. Roy

didn't tell him much, just that he was being assigned to the Commuter Group, and telling him he

would learn all about it when he got up there. So he was to report to me in the commuter offices

right away.

I asked Jimmy how much he knew about the commuter project before he came to us. He said not

much. People knew there was to be an increase in the number of trains being run, but everybody

was too busy to care much about what the Commuter

Group was doing. In the rest of Toronto Terminals, they

had no idea what was going on in the back room. "I wasn't

even told why I was to be there. So I just said 'yes, sir,' put

a smile on my face, and away I went to do the best I could".

Jimmy didn't remember what documents we thrust into

his hands. We must have already finalized the schedules for

the commuter train movements, because he simply used it

without giving it much thought. This was the way the

service would run, so now the problems would be how to

operate it. He recalled it had been foreseen that crews

would be running through Union Station, and that there was nothing in any agreement with the

running trades for crews to run on the different seniority districts east and west of the station. There

was some resentment for them to think that we wanted them to do that, without adding greatly to

the personnel on each side.

That wasn't all! The agreements stemmed from long years of negotiations, and recognised only

two different definitions of what constituted a day's work for a day's pay. One was "Straight-away"'

starting the trip at one terminal, and being finished at the other end of the run. The other was "Out-and-return", like a single trip to deliver or collect traffic. The two commuter trains that CN ran

were based out of Hamilton. Now the Commuter Group wanted crews to make several trips back

and forth between the outer terminals on two subdivisions yet, all in one day's work!

Quite often for a crew to be called "Straight away" meant being away from home for a minimum

of an eight-hour lie-over at an away terminal, and bunkhouses there might not be the most

comfortable places to lie over in. It could be a day or two before a return trip might come up to take

them back to their home terminal.

There was a clause in the agreement that we wanted to use that was truly unpopular with all the

crews. That was working a split shift, known as "Eight-within-twelve." This allowed for an unpaid

time of up to four hours, between two working sessions, for a total of eight hours paid. The

constraint was that neither of the two sessions could be shorter than three hours. If we chose to

exercise this clause, we could have some of our crews work the peak morning trains, be released

during the mid-day period, then operate the afternoon peak trains, as long as we complied with the

agreement.

Jim had started with the railway long ago, and had been fireman and engineman on steam and

diesel locomotives, so he understood well the attitudes now showing up among the operating

employees. There was a positive side for them to consider. Operating passenger trains was better

for crews than freight operations. Freight work required a lot of work on the ground, switching

cars, shunting back and forth by hand signals, and being concerned about clearing the lines for first

class trains. Passenger trains ran as first class trains, with right of schedule, and usually got in a full

day's miles quite quickly, without all that hassle. But most of the passenger trains running into the

Toronto District of the Brotherhood were originating outside, so there was very little passenger

work for Toronto to bid in on.

There came a slow recognition that here was an opportunity for Toronto crews to gain a lot more

passenger train runs. More than that, they would be home every night. This would be attractive for

the more senior employees, who had already had all that they needed of away-from-home working.

But they were not likely to be high-mileage jobs. This was not the best for crews in their middle

years, when they would be looking for the highest earnings. When finally the shifts were posted,

most of the bids came from experienced staff who stood high on the seniority list, or from juniors,

who did not stand to hold the high-paying jobs.

To try to overcome some of the objections to the split shifts, Jim and George Dollis together

worked with the Supervisors at area level to develop a rotating schedule, where the crews moved

progressively through each shift in turn. A crew coming back from their days off would work the

last shift of the day. Each successive day was one shift earlier, until they would work the first shift

of the day, then leave again for their days off. This gave a maximum of time off between working

that morning shift, then coming back two days later to work the last shift of the day. By the time

the service opened, everybody was "Gung-ho!" because quite a few passenger jobs opened up for

the Toronto people.

A lot of the planning was done with the Transportation Department on the Toronto Area, under

Bob Bowman. The commuter trains running through Union Station would have to be assigned to

tracks and platforms, given the track time necessary, and the necessary information given to the

tower men controlling the switches and signals. Much of this work fell to George Bushey, for

liaison with the Toronto Terminals Railway as well as the other activities of the Area.

When I asked Jim what else he could remember, he shook his head. "There was so much to do,

so many offices to talk to, so much pressure of time, and so much paper work to complete. You

can't expect me to go into all that. Maybe that does not answer your question. We sorted out the

direction we were going, operating timetables, manuals, and how to get them into the working

timetables."

That was one of the problems we had. This was so much different from existing operations that

it was not possible to go through all the authorization processes to get the schedules included in the

operating timetables. The trains would be introduced on line in a progressive manner, starting

about a week before inauguration day. This was not easy to include in a published timetable. We

had set a date for inauguration to be May 23, 1967, a date that did not fit the biennial publication of

system timetables. A separate time card had to be prepared, and our trains ran as "Extras" until the

Fall change of card.

Jim remembered how frustrating it was to have the lowest priority on the main line. There was

an occasion when one of our trains had to wait at Bathurst Street while a freight-switching move

was allowed to cross the main line in front of us. Extra trains had no priority under the proper

routine of dispatching at the control room. We worked closely with Clair Gingridge in the

dispatching office. It took a long time and quite a few visits to the control room up at the new yard,

to get the message across. Our trains would be carrying upwards of a thousand commuters to work,

and they had to get to work on time. A change in thinking would be needed, to keep them all

moving.

By the time matters advanced to this stage, we had brought in two more Trainmasters. Emmett

Roach joined us near the end of January, and Harry Dykstra came shortly after.

Emmett had come up through train crew service, so he had the background to foresee the

workings of train staff within the cars and on the platforms. With Jimmy concerned with the head

end, and Emmett for the cars, the preparation of manuals went ahead in time to start training the

employees when they came to us.

Harry was from the car Department, and had long

experience in coach yards, servicing the trains and

making them ready for their next departures. He told

me how he had started as Carman in the coachyard at

Hamilton. CN's commuter trains were based there, so

on weekdays the train crews took them to Toronto in

the morning, and brought them back at night. The

coaches were older cars, displaced from mainline

service, and not air-conditioned. They had toilets, so

they had to clean them and fill the water tanks. In

summer they would arrive in the coachyard with all the windows open, so one job was to go right

through closing them all up. In winter, they were steam-heated, so after arrival they had to be

connected to the steam pipes on the ground, to keep them from freezing overnight. Then in the

morning, when the locomotive came down from the roundhouse, they were disconnected from the

ground steam and coupled to the steam supply from the locomotive.

Those cars were lighted by gas, so they had to go through the cars turning the lights off after the

cleaners had been through, then in the morning go through with tapers to light them all again. The

gas went by the name of "Pintsch Gas". The cylinders were to be checked, and topped up or

exchanged ready for the next dispatch. Later the cars had electric lights, from batteries under the

cars, so the new work was to charge up the batteries. There was a lot of work, just servicing that

old equipment.

Our new trains would be very different. The locomotives would normally remain coupled to

their trains, providing head-end power for the lighting and the electric heat. There was no water on

the cars, so they could be allowed to stand without heat while they were out of service. Dispatching

a train should be so much simpler than with the old equipment. Now the trains serving Hamilton

would be running out of Willowbrook, meaning that the crews for these trains also came under the

Toronto District of the Brotherhood.

Teaming up with Bob Withrow and Doug Young, the Trainmasters worked on drafting manuals

for the train equipment, and with George Dollis and George Bushey on manuals for the train crews.

Together they formed a great team, and they were a great contributing factor to the success of the

whole operation.

Training the crews

We would need crews ready to operate our first trains, when they were ready for testing at the

Hawker-Siddeley plant. Another manual was drafted, giving the information that engine and train

crews would need for their operations on line. This was a document that would evolve as more

experience was gained from running the trains on tests.

Hawker-Siddeley needed a GO-Transit locomotive to do static tests on the cars as they came off

the assembly line, then we would need a whole train to take out for road tests and crew training. So

our first locomotive went back to the manufacturer in London to have the auxiliary diesel engine

installed.

Two Trainmasters, Jimmy Morrison and Harry Dykstra rode up with the first GO-Transit

locomotive to go from Toronto to the Lakehead. They also had members of the Equipment

Department from Toronto and Montreal with them. They had two cabooses coupled with the GO-Transit unit behind the locomotives that were hauling the freight train. It was early March when

they left Toronto, and the weather was cold, so both the locomotive engine and the auxiliary engine

were idling all the time to keep them from freezing. At every freight terminal, someone had to go

into the yard offices to explain what was going on, and arrange for them to depart on the next

available train.

Finally they arrived in the freight yard at the Lakehead, but it was another switching move to

place the locomotive at the plant. It was too late at night for the plant to be open, so they had to call

Doug Young down from his hotel, and get him to let them bring the unit in. At last they had it

inside the shop, and they could relax for the night.

Five coaches were ready when they got into the plant on March 6th, and the first cab car with

four more coaches were ready to put into a train on March 9th Getting the first train ready for the

road test was an exercise in itself. There were many adjustments to be made, getting the first set of

cars all ready, until they could say they were ready to take it out.

The first trip out was on Tuesday, March 21st. The arrangements were to run out to the west on

the Kashabowie Subdivision, towards Atikoken in Manitoba, reaching the siding at Huronia, mile

96.1. The cab car was leading, so the train would return with the locomotive leading. The

dispatcher understood what was going on, so he controlled the movements of all the trains on the

subdivision to allow this testing to proceed safely. Jim still worried they spent a lot of time in

sidings, clearing for other trains on line.

Stops were made at frequent intervals, and the doors opened and closed, so as to simulate the

commuter operations. Emmett Roach had come up for this trip. He was involved with the

Conductor in watching the operation of the doors, so he wanted to check that the outside lights

came on when the doors were open. When the doors

opened, he jumped out, just as he would in Southern Ontario, and promptly went up to his neck in snow!

He wasn't familiar with the land beside the track, nor

how deep the snow was. He was struggling and

shouting, so Jimmy had to rush to find a Trainman for

the two of them to pull Emmett back on board. He was

pretty wet, covered in snow. They brushed him off,

but it took the rest of the trip for him to get over that

little episode!

Kashabowie test train:

Photo George Dollis

These were really shakedown trips, both for the Trainmasters and for the engine crews. It was

the first time any of them had driven a "Push-pull" train in the push direction. The cab had the

usual handles for throttle and brake, and all the usual meters. But the thing that was missing was

the sound of a big diesel engine pulsating beside the cab. When the throttle was advanced, the

engineman did not hear the sound of a diesel engine revving up, but the train began to move

silently forward. Even judging train speed required a new sense of feel, very different from the

motion of a diesel locomotive along the track.

While I was talking to George Dollis about this, he made the comment: "I'll never forget the

expressions on the engineman who took it out. He had never seen a machine like this before, much

less driven one."

"Did you simply put him in the cab and tell him to

drive it?"

"Yep! It was quite interesting. He had Jimmy

Morrison and Bob Withrow as his guide and advisors.

He handled it very well."

The Trainmasters had gone through the planning

and construction of the cars and locomotives, so they

understood how the machinery worked. Their need

was to get the feel of running it, so that they would be

ready to train new crews, when they came to us. The engine crews needed more explanation, in a

non-technical way. The re-assurance was that the controls of throttle and brake in the cab car would

do all the same things as would have happened in the cab of the locomotive, except that in this

direction the locomotive was pushing at the other end of the train.

One big problem was in the technique for changing ends at the termination of the run. There

were valves to be closed and switches to put into the "Trailing-cab" position, to completely shut

down the controls at that end. If this job were not done correctly, then the controls at the other end

of the train would not function. An engineman could lose time if it required another walk the whole

length of the train to do the job properly. Just about all the staff lived through this problem at least

once during this learning experience.

As more cars came off the assembly line, they all had to have road tests before being accepted

for delivery. The need was to bring the cars down to Willowbrook depot, to start the

familiarization process for the workers there. The first train of cars arrived in Willowbrook on March 28th. By

now, more locomotives were available with auxiliary engines, so the staff started to get familiar

with servicing the equipment and preparing it for dispatch. There was sufficient length of track so

that new crews could run the trains back and forth down the yard tracks, under the guidance of the

Trainmasters. When the crews had learned to operate these gleaming new trains, there was a

noticeable enthusiasm building up, waiting for us to get them into service.

For opening day, I wanted to be sure that we would not have untried equipment giving problems

out on line in the first days of service. I had arranged for our first four trains to be transferred to

Fort Erie, where CN had track space on the Dunville Subdivision that could allow us to put miles

on the trains, clear of the traffic in the Toronto Terminals. In this way I could be sure that the first

trains into service had already run at least 5,000 miles in simulated commuter service. We sent

commuter crews from Toronto to operate these trains, accompanied only by a pilot from the Fort

Erie shop, for protection of the train movement.

This sequence of events provided a steady build-up of crews with adequate experience to be able

to take the train into service on inauguration day.

Staffing the stations

At the same time as the depot at Willowbrook and the train equipment were developing, the

government workers under Bill Howard were getting on with preparing the stations. An earlier

chapter describes how we had developed the ticket system the previous year and planned the way

the stations would operate. It was time to recruit someone to administer the staffing of the stations,

and to train the Station Attendants before opening day.

The best candidate was Don Martin, who came on staff with

us January 1st, 1967.

In 1995 I traveled to Kincardine, on the shores of Lake

Huron, where Don was resident in a hospital there. Don said his

biggest memory of those days was the planning for the staffing

and the operation of the stations, before the operation could start.

With Jack George and Reggie Corrigan, they worked on the

accounting procedures, the forms that would be needed to keep

control at the stations, and the handling of the moneys taken in.

Don was proud to produce his GO-Transit hat, with the green band that is discussed in the

chapter on "Construction by Government"

This was where Don helped us to develop further the ticket concept. In discussions with Bill

Howard and the fixing of the fare tables, we saw the need to be able to sell multi-trip tickets. The

problem with the old style of ticket, with its punch points, was that the price usually was an odd

number of dollars and cents. It was a slow process of selling just one ticket, taking in the payment

and making change. For the traffic demand we hoped for, we needed to sell tickets much quicker

than this. So we designed an arrangement of a book of tickets. The individual pages of the book

comprised three single-trip tickets in a row, using the same colour codes, and the number of pages

was matched to the fare level and book price at that station. This allowed us to create books for a

selling price of a good round figure, $5.00, $10,00 and $15.00. Clients could offer a single money

bill, and receive a book, with no delay making change.

A passenger took out one ticket for each trip, and treated it just as a single ticket, dropping the

first half at the station of origin and the other half at the destination.

There were four kinds of control to be designed and forms created to suit.

We had to have revenue reports of the daily sales at the stations, to know what revenues had

been taken in, and to balance the books when the cash went into the bank. Don felt that this was the

most difficult of all the forms to finalise.

The level of stock held in the stockroom must be known all the time, so that we could order new

printing before stock would run out.

We would need to know day by day what had been the levels of sales of each type of ticket, then

issue the proper quantity of replacement, and deliver them out to the stations along the line.

We needed reports of the half-tickets deposited by passengers entering and leaving the stations.

These yielded the statistics of passenger loading on the trains, and where passengers were traveling

to and from.

The Accounting Clerks were helpful in setting up these controls, in their preparation of

accounting forms for the reports to Government.

Every ticket carried a serial number. Before starting the work on shift, the attendant noted the

serial numbers of each type of ticket. At the end of the shift, reading the finishing serial numbers

told how many had been sold, and how much revenue must go to the bank.

Finally, each station was to have a form, with a column for each train by number and time of

day. The attendants would keep a running count of the exiting half-tickets for every train. As soon

as the last passenger had exited, the attendants would sort them by station of origin, by the other

colour on the ticket portion, and enter the figures in the columns. These forms would come back to

the commuter office every morning. Before starting the day's work, I would have on my desk a

statement of how many passengers we had carried yesterday, the trains they had traveled on, which

stations they had exited at, and where they had traveled from. This would be the way traffic

information would be relayed to the Government Department.

Under the ticketing system, the entry halves and the exiting halves were of the same colour.

They were to be kept separate and sent to the commuter office for audit and destruction in the

municipal incinerator. There were at least two ways we could audit the activities of the stations.

We were to do spot checks, repeating the sortation, and verifying the reporting of tickets collected.

Then from time to time, we could match the numbers of the ticket halves deposited at a station,

with the corresponding halves collected at the destination stations. This was an accepted way of

detecting whether there might be fraud in revenue control. We needed reports of the half-tickets

deposited by passengers entering and leaving the stations. These yielded the statistics of passenger

loading on the trains, and where passengers were traveling to and from.

The Accounting Clerks were helpful in this, in their preparation of accounting forms for the

reports to Government.

The other need was for the furnishings at the stations. Each ticket booth would have to hold

sufficient tickets for at least one day's sale. The attendants needed tickets displayed in racks, so that

they could quickly sell the one the passenger asked for. In view of the selected shape of the tickets,

Jack George had a friend in the metalworking business, so they put their heads together and made

some experiments with various ideas. From that, Don arranged for the manufacture of ticket

holders and dispensers that could be closed and locked up when the attendant departed. A safe was

provided to hold the ticket stocks for the next few days, until the receipt of the next delivery to the

station. The dispensers at Union Station were about twice the size of the ones for the stations on

line, because they had to hold so many more tickets.

This was another place where Jack George's knowledge came into play. The traffic forecasts

gave an estimate of how many travelers we might expect at each station, but not a breakdown of

where they would be traveling from and to. Since the service was not yet running, we had no field

experience to base it on. Jack had to use his judgment to calculate how big should be the first order

for ticket printing, how much space they would need for holding in the stockroom. The bulk of the

tickets would be to and from Union Station, but we had to be prepared for travelers going between

the other possible combinations of stations. From that, he calculated how big should be the ticket

stocks at each station, according to the origin-destination combinations, and how often we would

need to deliver replacements to keep the stock up.

We

finalized the design of tickets, then we prepared the purchase orders, and oversaw the

printing of the ticket stocks. The tickets required a safe location for storage facilities, so we

arranged a series of shelves in an air-conditioned room adjacent to the police offices in the station.

With all this worked out, came the time to recruit the Station Attendants. It was a big part of

Don's work to plan the station staff and station hours. To coordinate with the hours of train

operation, the stations would have to be manned between 0530hrs until 0040hrs the next morning.

Two Attendants would be needed at each station during the peak hours on weekdays, but not

always double on weekends. Between peaks and in the evenings, one Attendant would suffice. That

meant some of the jobs posted would be on split shifts. Here also the positions and the hours of

duty had to be negotiated and agreed with the Brotherhood.

In the chapter "Setting the scene" of this book, there is information about the rapid growth that

was taking place around Toronto, and how the freight shed was being moved from Simcoe Street

into a new facility out at the new yard. This shed would be highly automated, to use fewer people

than the old one, so there would be some employees released for other work. The jobs in the new

shed would be bid on seniority, so any employees low in seniority would not have chance to hold

jobs there. Some of the employees did not wish to travel the long distance to the hump yard out at

Maple, so they also wanted another alternative.

So Don worked with the CN Personnel Department, and the new jobs were posted for the

Station Attendants. This was a great relief for the people who did not stand for higher seniority

work, and might have been facing a lay-off. It was good for us, too, in making available employees

who were already established in the railway.

As Don said: "All positions had to be advertised by regional bulletins to the whole Toronto

Area. We thought we might have a hard time filling all those positions, what with the strange hours

of duty and the split shifts, but the response was overwhelming. We had advertised 105 positions.

Out of all the bids we received, we accepted about 150, knowing they would have to attend the

training classes in ticketing and accounting procedures. Out of all those who attended the training,

we kept 125, in case some of them might not qualify for meeting the public. This did happen."

CN's Personnel Department assigned Les Laird and one other Officer to work with George and

Don to develop the training courses. Don couldn't remember who was the other one, but I think it

was Joe Campbell. I tried to contact Joe, but seemed unable to find him. Time was running out on

me too, so I had to start writing without all the contacts I would have liked to make.

Anyway, the trainers had to train themselves first on the material we had prepared, then they

decided the candidates would need two days of training. I was able to make a speech of welcome to

all the candidates together on the first morning, then they were split into smaller classes lasting two

days each. The training officers did a terrific job, and everybody was happy with the result.

When the course was finished, there were 120 qualified employees for us to staff in right away, and

those not taken immediately were qualified to move in as vacancies arose.

We had to do some quick action when the success list came to us. The uniforms had been

ordered under CN's standard practice, on the presumption that the candidates would be all men

coming out of the freight shed. Not so! Two of our personnel who had qualified were women from

the offices. The contracts for supply of uniforms did not envisage uniforms for women, so we had

to do some quick thinking about how the GO-Transit image should apply to them. We talked with

Jessie Smith and Reggie Corrigan about this question, and decided we should ask the Contractor to

substitute skirts for them in place of trousers.

I was able to interview Stella Hanula, where she has retired to her

house, not far from our Danforth Station. Stella was one of them, and

she quickly showed the competence to be the Senior Station

Attendant on the afternoon shift. This was like the job of a foreman,

overseeing the Attendants and their ticket stocks. She thought the

other training officer was Mike Hollingsworth. So much for our

memories after 30 years!

Stella was happy that we had chosen skirts for the women, and she

continued to wear them right up to retirement. Some of the later

recruits came in the years when slacks were more in vogue, and the

stations could be cold places to work. So the option of slacks was

offered.

Stella Hanula at home

Another item needing quick action was personal

identification for station staffs and supervision who should have authority to pass in and out of the

ticket booths in the course of their work. we were already familiar with a process that started from

plastic sheet that had multiple layers that could be exposed in turn by cutting away the covering

layers in a delicate machining process. With this we could purchase badges to be worn by

appropriate staff personnel, as well as identifying persons

of authority to the passengers. We discussed this with the

manufacturers, who offered us a design of badge that could

display the GO-Transit logo with a space beneath where we

could paste a plastic strip showing the staff member's name

for our stock control.

Each strip started as a black plastic band that passed out

from a hand-operated punch. The punch would push

outwards with each letter in turn, that showed up white on

the black background. Preparing the strips for the names

fell to Jessie Smith. The list of successful bidders for the

station staff positions gave us the whole series of names

that Jessie would punch out and attach on the badges. She spent an arm-stiffening weekend

punching out name after name, but joyfully carried them in ready to be issued to the station

attendants. The photo shows a badge worn while on duty with GO-Transit.

<< 11: Construction by Government || 13: Accounting >>