10: Building the plant

<< 9: Designing the train schedules || 11: Construction by Government >>

When the commuter group first came together, time had already advanced into early Fall of

1965. A lot of work was going on throughout the Winter of 1965-66, all at the same time. The

transportation staff of the Area was deep into the tasks of changing the way the freight services

were operated. Transfers that used to come out of the Mimico freight yard were coming out of

the hump yard, and long haul freight trains went into the access lines instead of running through

downtown Toronto. We were visiting potential station sites, and finalising the location for the

service depot at Willowbrook, the commuter train schedules were being drafted and revised with

all concerned, and the line occupancy study was in progress by the Transportation Department in

the regional offices.

So the Spring of 1966 arrived, when the commuter group had defined the station and depot

needs of the service. Now we had the preliminary plans for the station platforms to be built and

fenced at Pickering, Rouge Hill, Eglinton, Scarborough, Danforth, Mimico, Long Branch, Port

Credit, Clarkson, and Oakville. The decision had been made that there would fences between the

tracks. Passengers would not be walking across the tracks. Instead there would be pedestrian

underpasses to reach the tracks on the other side. There would be pedestrian underpasses at

seven stations, and an overpass at Danforth. Storage tanks for diesel oil, and fueling stands to

pump it into the locomotives were to be put in at Willowbrook, as well as a new shop for indoor

work on the train equipment. The expectation was that we would rely upon the facilities of CN's

Engineering Department to execute the work while Harry Kier would oversee preparation of the

engineering drawings and the work in the field.

Then the results of the line occupancy study came to hand. A third track was required through

Port Credit, Long Branch, and Mimico, and another between Scarborough, Eglinton, and

Guildwood. All along the line new crossovers would be put in for switchers to clear the line at

industries, with a general upgrading of track so that the commuter trains could make their runs in

shorter times. The grade separation at Clarkson was to be added to the one already planned at

Dixie Road. Finally, a new C.T.C. signaling system would permit the dispatchers to direct trains

into the proper tracks, for the commuters to make their station stops, while the non-stop trains

would run passed them on the other tracks. This new amount of engineering work was far more

than the seven people of the commuter group were organised to handle, so I took the problem up

to Eric Stephenson, the General Manager for the Region, and he brought Jack Cann back into the

picture.

When construction work was coming to an end at the hump yard, Jack had been assigned on a

job to work with the Ontario Northland Railway, so he had been in North Bay for the whole

year. The work there was done, and Jack came back to see Eric Stephenson about his next

assignment. That was easy! Here, just waiting for him, was a big upgrade on the main line

through Toronto, and a tight deadline to finish it. The new service was due to commence in the

Spring of 1967, and here it was already Spring 1966.

I asked Jack what was his reaction when he saw the amount of work ahead and the time

available to do it. His reply came without delay: "It didn't bother me at all. When we did the

yard, we finished three or four months ahead of time. Now there was an election coming up, and

the Government had made public commitments about when the service would start, so that

became the target date to have it ready for operation, even if not fully completed. I had Eldon

Dolphin and Bob Field with me on the yard, so I knew their capabilities well. We would have to

organise getting quick delivery of track and signal materials. The biggest problem would be

planning track time, with all the other train movements going on." So Jack picked up the final

responsibility for getting the construction done, and he called upon the able support of the same

staff members who had worked with him on the access lines to the hump yard—Eldon Dolphin

and Bob Field.

Eldon brought to the hump yard a long experience with the Engineering Department of CN,

and had managed the construction of the access lines, so the same skills would be needed to get

the new work done on the lines through Toronto. Bob Field had developed and installed an

improved signal system to move freight trains in and out of the yard faster.

It required close liaison with Norm Hanks in Transportation,

because the detailed listing of the needs of tracks, interlockings,

and signals on the main lines between Oakville and Pickering

were coming to hand only as fast as the study of line capacity

could bring them out.

They were friends then, and they are still. I was glad to be

able to meet with each of them, and go over their experiences

while they looked back on it. They worked long hours. All

commented on their own personalities, both admitting to being

strong in their own opinions, and going head to head on what

and how to get the work done in time. There was one particular

event they both remembered. They were working together at home in Oakville, when Eldon

became so angry that he stood up, saying:: "That's enough, I'm not even staying for that". He

opened the door and walked out. Then he came back in, saying: "But this is my house!"

The west end

At Port Credit, before the work started, there were only the two main tracks that went straight

through between the station platforms. The sidewalk and the existing CN station were on the

south side, so that was where the commuter ticket booths would be placed. So the new third

track would have to be built on the north side of the platforms. The land available for parking

was on the north side, so two pedestrian underpasses were needed, an open one to pass the

commuters from the parking lot to the ticket booth, the other for the fare-paid passengers from

the ticket booth to the platforms.

While the Mimico freight yard was in full operation, there was a sidetrack that took off on the

south side of the main line just east of the station. This was the entry track into the yard, where

freights would be held out, whenever the yard was too overloaded to let them in right away. Now

that the entry track into the yard was out of service, the idea was to upgrade it and make it the

third main track. The three tracks east of the station did not line up with the three tracks through

it, and all three tracks had be slewed over by the space of one track, just east of the station. The

old entry track connected with the south platform track and the old north main line track

connected with the new north platform track. Then all three tracks merged into two main tracks

on the Oakville side of the station.

The upgrade of the entry track created a problem at Long Branch. Space had to be created

between the entry track and the old south main track. At that point, the tracks are on a

downgrade westward to the creek, and were just coming out of the deep cut under Brown's line.

So some excavation had to be done to move the track over. To minimize the total cost, we

accepted that the ends of the platform did not have to be full width all the way, so the east end of

the south platform at Long Branch tapers down to four feet wide.

The whole job on the west end comprised the new track and platforms at Port Credit,

upgrading the entry track to become the third main track, widening the cut at Long Branch,

relocating the main tracks through the old Mimico yard, building the new depot at Willowbrook,

installing crossovers and signals all down the line, and putting in the pedestrian underpasses,

platforms and fences at five commuter stations.

The east end

The layout of the tracks between Scarborough and Guildwood differed from the west end, in

that the centre track would not serve those station platforms. Every commuter train on those

lines must use the side tracks. All three tracks were up to main line standards, so this would not

impose unusual limits on speed.

By the time the work progressed to this point, the fieldwork was advancing faster than the

drafting office could keep up. Some parts of the work on the ground were done according to the

engineer's hand sketches that would be converted into official drawings while the work went on!

The new third track from Scarborough to Guildwood had to be ballasted in the month of

February, which is not the best time for it, but that was necessary in order to have it ready in

time.

The work on the east end comprised adding a crossover to the track layout at Pickering to let

the commuter trains reach through the overpass at Liverpool Road, putting in more than four

miles of new third track, pedestrian underpasses at Rouge Hill, Guildwood, and Eglinton,

platforms and fences at the stations, and new crossovers and signal over the whole line.

Signals

A completely new system of signal was adopted, in order to

accommodate the mix of intercity trains, commuter trains, freight

transfers, and switch engine moves. I traveled to Winnipeg to

meet with Bob Field, who played a big part in composing the

system. He had been promoted out of the ranks of the

dispatchers, so he understood the needs and complications of

controlling the safe movements of trains, from inside a

dispatcher's office. He was Superintendent, Toronto, when he

had been designated to be Superintendent of the new hump yard

when it opened, so Jack had given him the responsibility of

planning the access lines to meet the needs of the yard.

With his experience, he had already recognised that traditional signal systems were strictly

oriented to preventing unsafe movements, in effect telling the trains what not to do. A clear

signal gave the train crew permission to go ahead on the track, but no more information

concerning what to expect next. The control panels presented to the dispatcher only a picture of

the situation on the ground, what signal blocks had trains in them, and that aspects the signals

were displaying. The Dispatcher then operated the switches to line the route and cleared the

signals to let the train proceed.

As Dispatcher, Bob had wanted to know that the future was equally well under control as the

present. He wanted the signal system to talk back to him, to look ahead, to alert him if trains

would be running into delays at the next signals, and to take action in time to prevent

interference with the smooth flow of traffic. The signals had to tell the trains what to expect next,

how fast they could run, and whether a restrictive signal happened to be ahead. If everything was

safely under control there should be no need for the dispatcher to interfere at all, the system

should do everything automatically to keep traffic moving as it should. This was what he had

achieved on the access lines, and it kept the trains moving in and out of the yard excellently. The

only thing he did not get, that he wanted, was to have the signals tell the train what speed they

could run, that is "speed signaling", instead of as it was, telling them which tracks they would be

on, that is "route signaling". It was too much of a departure from experience, to make a change

like that, all in one big jump, so that did not get done there.

By the time Transportation had recognised how essential it was to install a complete C.T.C.

system for the new commuter service on the Lakeshore Lines, Bob had been transferred to

System Headquarters as Manager of Rules. The Area Manager, Jack Spicer, called him to say

that full signaling would be needed, and could the principles from the access line be applied on

the commuter lines? Now the second half of the jump could be made.

Bob did most of the work out of his office in Montreal, calling also on the support of the staff

of the Signals Department, under Don Green. The concept still was a departure from tradition, so

it was not easy to convey the new principles. It had to be negotiated with the Railway

Transportation Commission in Ottawa, then a separate set of rules had to be developed to put in

the working timetables, because the standard rule book did not give instructions for this type of

signals. Finally approval was received, then orders had to be placed with the signal supply

companies, and the same exercise gone through with them. So the signal system on the

Lakeshore Lines is the first that uses speed signaling, according to the criteria that Bob had

developed when the hump yard was being built.

The signal installers

I was lucky to be able to bring together three of the signal installers who worked on putting in

the new system. I was halfway through our meeting when I asked Jack Shaddock if he could tell

me who it was that Jack Cann sent to the manufacturers plant in Pittsburgh. Leo McKenna

jumped in. "That was me! We went down to Union Switch and Signal on a two-week training

course, to learn the electronic system they would have us putting in. Dr. Coprandt designed the

system, so he gave the lectures. That was how we first learned what kind of a code system we

would be installing."

"Then was it you, yourself, who was to be chaser at the plant?"

"No. That was Bob McGill. Mr. Cann wanted an expediter down there all the time to push

things along. He had a deadline to meet, and he made it! They said I knew all about it, so I might

as well stay at Concord. They made me Supervisor at the control room! I had a crew in there. We

installed all the racks and the consoles."

It was Jake McGill who was Supervisor of Construction out on line. Mostly he had been doing

grade crossing protection installations. As he said "I just sort of got nominated to do the GO-Transit signals. It was kind of a panic situation.

They wanted everything done in a hurry."

"There was that phone call that came in to the

control centre. Someone had been going over the

overpass and saw a man lying between the tracks

at Brimley Road. They phoned CN, and CN

relayed it to me. I went in to Jack to tell his field

man to get up off the tracks!"

"What was he doing?"

"He was checking out the signal. He had to call

in to report each time a signal changed. Instead of

standing to one side, the simplest thing was to lie

down in the space between the two tracks. When the field man got the message by radio telling

him to get out of there, he wondered how we knew where he was!"

"One day we had a bomb scare. It was nighttime when they phoned me. One of the GO-Transit trains had seen this silver box, with a black and white pipe around it. So everything had

to stop. When I got hold of the maintainer, he said that was his transducer. That was part of the

signal circuits of the grade crossing protection. One of them had gone defective. Normally they

were housed out of sight in the track. There wasn't time to properly house the replacement yet

keep the trains running, so he simply fixed the replacement in full view."

All three remembered the signal work when the pedestrian underpasses were going in. The

rails had to be cut and removed, so the signal circuits also were cut. After the underpass was in

and the rails replaced, the signal staff had to bond the joints to restore the circuits, then test the

signals to be functioning correctly.

Pedestrian underpasses

The construction of grade separations usually was based on standard designs in the Engineer's

office in Montreal. Then the construction work would be let to outside contractors. The tight

deadline for getting the commuter service going meant that the same technique could not be

used. There was no time to have tracks diverted at eight stations, for a total of ten underpasses,

and then lay in the platforms after that. So the problem was put to the Regional Bridge Engineer,

Napier, and the Regional Construction Engineer, George Workman. Together they assigned it to

John Jeronimus, who already had a background of bridge engineering.

I asked John what was his one big memory about the start of the commuter service. He said it

was the short time period given to him for the design and installation of the pedestrian

underpasses. This was a new and special development, and it still represents an important step

forward in railway engineering, so I will give most of the story in his own words.

"The criterion that was given to me defined the conditions under which the design and

installation was to take place. Ten underpasses, to be designed, constructed, and installed in

track, with the minimum of interruption of line operations, at least cost, and ready for service in

less than twelve months. The design was all done locally, in the regional offices. There was no

time to erect falsework to construct them on site, so we decided to go with segmented

construction, with installation to be done on weekends. The segments were like square rings,

made under contract in yards that specialized in

prefabricated concrete, and shipped to site on flat cars. The

quality and workmanship had to be exact, so we called for

steel forms. When they came, they had a smooth concrete

surface that had to fit together very well, to prevent

infiltration of water. We developed special seals for the

joints. We mounted them on steel grillages, so that if there

would be any settlement, it would be perfectly even. The

grills lay on the excavated surface, then ballast was put

into the spaces. The rings were craned on to the grill, then

pulled up tightly in place. Then the masonry gang pumped

grout through holes in the floor to fill the spaces in the

ballast, and make a solid bed to carry the weight of the trains that would pass over it."

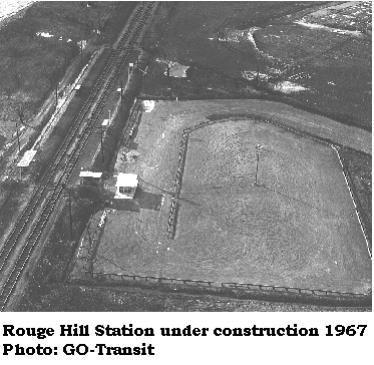

I watched the first installation, at Rouge Hill. The train service was stopped so that the tracks

could be cut and the excavation taken down deep enough, and leveled off to receive the grill.

Then the rings were put in place, the excavated material was compacted around the tunnel, and

the tracks replaced. This first tunnel took only 14 hours, until the train service was restored. With

experience, times became shorter, and the quickest one was completed in eight hours. Then the

stairways could be installed at a later date, once the tracks were restored.

I asked John why they had not wanted to install underpasses 10ft (3.0m) wide inside, that I

asked for to allow three people to walk side by side, while they had been pressing me to accept

8ft (2.4m) wide, that was only wide enough for two. He explained it was a matter of the lifting

capacity of the cranes they would be able to get to the site. The rings for a 10ft tunnel had to be

shorter to keep the weight within the limits, so it would need more rings, take longer time and be

more expensive than would the 8ft size. In the end we accepted 8ft tunnels where this size could

accommodate the pedestrian flow, but we got 10ft tunnels for passenger flow off the platforms,

where passengers getting off a train would wish to exit as quickly as possible.

There were unexpected problems when excavating, such as with rock at Oakville, and

flooding at Long Branch, but the end result has been very satisfactory, and there has been no

measurable settlement over thirty years.

The construction in the field

The transportation needs were being identified through Norm Hanks, and the design

specifications were being drawn up by Eldon Dolphin, but skilled supervision was needed out in

the field, to ensure that the specifications were complied with, and to keep progress on time.

With so many activities in the whole Toronto Area, Eldon was running short on available staff

with field experience to supervise the new work for the commuter project. But he knew an

engineer, Duncan McClennan (Dunc), working in the bridge office in Winnipeg. I asked Dunc

when he first heard of what was about to happen in Toronto. I put a whole series of questions to

him. I would like to tell his story in his own words.

"It would be June or July, 1966, when I was working in the bridge office in Winnipeg, as

Structural Field Engineer. I received a phone call from Eldon Dolphin. He was running out of

people with grading and structural experience. They were all tied up in other projects, so he had

to look further west. He explained a little bit over the phone, then asked what was the quickest I

could be in Toronto, like, maybe, tomorrow! I accepted right

there, and cleared it with my boss. With my wife and the two

small twins, we piled into the car, and headed to Toronto. The

biggest thing I remember when he met me was: "We've got to do

this, and this, and this, and this is the date we have to finish it!" I

said I thought we didn't have time to do all that. That was when

he said: 'I don't want anybody here who says we can't. I want

people who will tell me how we can finish it in time'. So I did it!

I didn't know Toronto at all. So much so that I bought what I

thought was the Toronto paper to look for homes. It was the

Globe and Mail, not the Star or the Telegram!"

"I remember most of all the time-bind. We had less than a

year, to design, build, and signal the new facilities, and turn them

all into operation. We did such things as ordering twenty left-

hand and twenty right-hand turnouts for the main line, not

knowing where they would go yet. If they were not ordered

immediately, we would not have them in time to go into service."

"There was work going on all along the line, so I had to drive every where. I had to leave

home in Oakville not later than 0530 in the morning. Later than that, it was stop-and-go traffic.

We worked long hours, seven days a week. I was seldom home before eight or nine at night.

Signals were a big part of the operation. We sent our own people down to the signal

manufacturer's plant, to act as expediters. There was a lot of contact. Much of it was "Design-and-go".

I asked Dunc how he got the information, to say what was to be built in track and signal.

"That came from Eldon Dolphin and Norm Hanks, working together on a day-to-day basis.

You know they are both very strong-willed. I remember them almost nose-to-nose in a meeting

one day, ordering those expensive switches, arguing about whether we should order twenty-five

or twenty six. What was one extra, if we had to redesign it! We had to order now, or we would

not have it if we needed it."

"I worked with John Jeronomus when he was designing the underpasses. I was securing

contractors and equipment to do the installation. We would get everything ready during

Saturday, to cut the track after the passenger train had gone through, then work through the

night. I remember the police coming out to me at Port Credit, and shutting me down. I wanted to

start at 0430 in the morning, and there was a noise bye-law! It was a learning curve. With each

one, we got into a routine. With the same contractors, the same operators, it became teamwork.

They all knew what the next step was."

"I did not need to be involved much in the road grade separations. The people in the

Engineering Department had all the experience necessary in that department. I was more into the

grading, the new trackage, and the signals. No one thing stands out in my mind now, because it

was all crisis, get it done now!"

So what did you move on to after this work was done?

"It was a slow transition. We were doing an upgrade of the yard at Oshawa, so I still had to

drive right through Toronto each day. When finally the GO-Transit service was running, I

noticed an immediate diminution in the intensity of traffic on the Queen Elizabeth Highway. A

pity we did not put in much bigger parking lots at the stations right away."

Street access, ticket booths and parking lots

Work off the railway right of way was taken over by the Government of Ontario, so this was

the work that Bill Howard supervised. Some of the lands were owned by CN, but for some

others there had to be negotiations with the owners before they could be taken over. There were

other responsibilities that he had to look after, so next is a separate chapter to give a broad

outline of "Construction by Government" that he was responsible for.

<< 9: Designing the train schedules || 11: Construction by Government >>