10: Carabobo

<< 9: Boyacá || 11: José María Córdoba >>

Of the countless battles won by Bolivar in the course of liberating the Spanish colonies in the South American

continent, perhaps Carabobo was the most important.

For, if in each of these victory was the result of the Liberator's superior military genius, and if at Boyacá

the elements of his triumph in crossing the Andes were audacity, surprise and improvisation, offsetting the patriot

army's almost complete lack of food supplies, military equipment and adequate clothing, at Carabobo these three

important factors prevailed: foresight, organization and military strategy superior to that of the enemy.

To these three factors could be added another, without which success might not have been attained-luck.

For it is a proven fact that to achieve success in any human activity, including business as well as games of chance,

such as cards, there is requisite, over and above the factor of knowledge, another indispensable ingredient-luck!

The combination of these two elements was decisive for Bolivar. Thus, at Carabobo, preparedness,

audacity and superb strategy, together with this last ingredient, fortune, resulted in his smashing victory.

Carabobo was the climactic battle in which this colossus, operating in a territory ravaged by ten years of

bloody warfare, where one-third of the populace had been annihilated, and totally lacking the resources to provide

even the essentials for subsistence, he created, in less than two years (the period between Boyacá and Carabobo) an

army capable of destroying the military strength of the royalist armies in Venezuela, then considered the most

powerful fighting forces in all of Spanish America, from Mexico to Patagonia.

Background

Analyzing the various factors that contributed to Bolivar's stupendous victory at Carabobo, the following

conclusions appear relevant:

1) Foresight. In numerous communications to his lieutenants, who were scattered in small groups throughout the

vast Venezuelan territories with troops he planned to assemble into a single army greater than that of the enemy,

Bolivar gave instructions to avoid engaging in any decisive action without having forces sufficiently superior to

those of the Spaniards to insure victory.

2) Organization. During the twenty-two months preceding Carabobo, Bolivar, struggling with infinite patience

against almost insurmountable obstacles, was principally occupied in obtaining foodstuffs, equipment and clothing

for the enormous concentration of troops with which he planned to give the enemy the "coup de grace".

In territories where the essentials of life were almost totally lacking due to the length of the war, it was the

task of the Liberator to secure sufficient foodstuffs and cattle to feed an army of some ten thousand men. Moreover,

the small resources of the Treasury were of necessity used to purchase arms, ammunition and equipment. As a

result, the salaries of the troops were in arrears, and desertions were numerous. To prevent these as much as

possible, Bolivar established the most rigid discipline, and issued minute instructions to his lieutenants in this

regard.

3) Strategy. Some critics of Bolivar have tried to show the Liberator as a military leader with no preconceived plan,

who always improvised his military operations on the field of battle.

In his "Memoirs" Napoleon denied the suggestion that his battles were the outcome of a formula prepared

beforehand. "Never," he said, "have I had a preconceived plan of operations" (`je n'ai jamais eu un preconçu plan

d'operations'). According to historians, this assertion was at best a "half-truth". For, while it is admitted that each

military operation must of necessity contain a certain degree of improvisation, in each of the great battles won by

Napoleon, as well as those of Bolivar, there are definite indications of certain basic principles of strategy planned

beforehand and invariably carried into practice.

Carabobo represents the quintessence of these tenets, as will be seen later in the "Plan of the, Campaign"

and the preliminaries of the battle.

4) Public Opinion. During the years prior to Bolivar's smashing victory at Boyacá (August 7, 1819), public opinion

in Venezuela, at first favorable to the liberating crusade, had become hostile because of the people's sufferings

during the long years of ruinous warfare, as the frequent defeats of the patriots resulted in bloody reprisals by the

Spaniards on the helpless towns.

In this desperate situation Boyacá was the beacon of new hope and light for the devastated Venezuelan

provinces. The unexpected liberation of Nueva Granada (Colombia) by a handful of heroes led by Bolivar rekindled

the fire of Liberty in the hearts of the oppressed Venezuelans. This sudden change in public opinion greatly helped

the Liberator in the development of his "Plan of Campaign" at Carabobo.

5) Military Cohesion. Another favorable result of Boyacá was that of re-uniting under the banners of the

government and the central command those of Bolivar's generals who, after an isolated victory in the far off

territories where they operated, were inclined to ignore or disobey the orders of the General-in-Chief.

One of these was General José Antonio Páez, the hero of Carabobo. Before Boyacá, Bolivar, en route with

a small army to liberate Nueva Granada, ordered Páez to help this venture by mobilizing his troops toward Cúcuta

(a city situated in Nueva Granada on the Venezuelan border). Páez not only ignored these instructions, but further

considered Bolivar's plan ridiculous. According to a widely known anecdote, he remarked that it was "Like trying

to grab Heaven with your hands". The Boyacá victory completely changed Páez, who subsequently gave blind

obedience to the Liberator's orders, as demonstrated at Carabobo, where his bravery, together with that of his

llaneros (cowboys of the pampas), was greatly responsible for the crushing defeat of the enemy.

6) Fortune Favors the Liberator. As a result of the military revolt in 1820 by Riego y Quiroga in the Spanish

Peninsula, in favor of a Constitutional Government and against the dictatorial powers of King Ferdinand VII, one

of the first steps taken by the newly constituted Spanish Parliament was that of trying to conciliate the dissident

colonies in South America, and bring them again into the fold of their mother country. For this purpose, pertinent

instructions were sent to Don Pablo Morillo, General-in-Chief of the Spanish Armies in Venezuela and Nueva

Granada. As a preliminary step, a six-months' armistice was signed in the city of Trujillo on November 25, 1820,

between the royalists and the patriots.

This armistice, as well as the Spanish Revolution, was favorable to the patriots, because:

A. This truce in hostilities, together with the fact that public opinion was favorable to the Republican side,

permitted the Liberator to organize and improve the condition of his troops and prepare them for the forthcoming

campaign situation in the Peninsula, created by the Revolution, the Spanish Government was unable to send to its

armies in Venezuela the timely help anticipated by the Spanish Generals.

In conclusion, the superb strategy of the Liberator and the audacity of his genius in taking advantage of the

favorable contingencies presented by the enemy, were the inexorable forerunners of his victory.

The Plan of the Campaign

After his victory at Boyacá (August 7, 1819), Bolívar's chief preoccupation was to liberate his country (Venezuela).

Four months later, he wrote to Admiral Brion about his plans, saying in part: "I come to liberate Venezuela, whose

fate seems decided, because with the resources of both men and money that Nueva Granada has given me, I have

created an army far superior to that of the enemy . . ." And a week later (December 20, 1819), he wrote to General

Santander at Bogotá: "I have instructed General Páez not to engage the enemy in any battle unless they are

inferior in numbers and he is certain of destroying them without himself suffering heavy losses.... Therefore it is

probable that as soon as all divisions of the army together amount to not less than 9,000 or 10,000 men, I will start

the Western Campaign".

Among the many campaign plans of the Liberator to free his country, the two outstanding were Plan A

and Plan B. The first one, considered the best, was discarded for the second, which, although inferior, afforded

better food supplies for the patriot army.

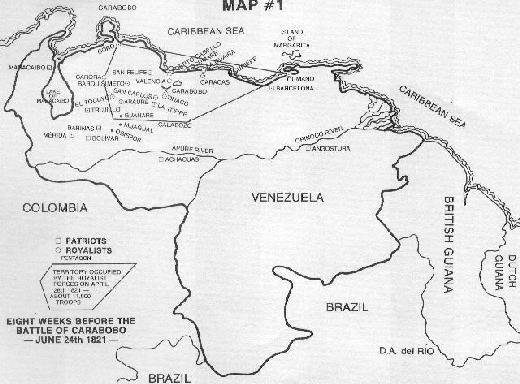

For a better understanding of this plan, we will briefly describe the positions occupied by the royalist

armies on April 28, 1821, when-one month before its expiration-the armistice was broken and war was resumed.

The Spanish armies enjoyed a privileged strategic position in Venezuela. Their contingents, consisting of about

10,000 to 11,000 men under the Supreme Command of Field Marshal Miguel de la Torre1 controlled all the

northern coast of Venezuela from Coro to Cumaná, a distance of about 600 miles. This insured them free

communication with the exterior. They also controlled the most populous and wealthy Northern and Central

regions of the country from La Guayra and Caracas in the north to Calabozo in the south (a distance of about 195

miles), including Valencia to the west of Caracas and south of the coast, as well as San Felipe and Barquisimeto

and the important towns southwest of Valencia, San Carlos, Araure, Ospino and Guanare (the distance between

Caracas and Guanare is about 250 miles).

This advantageous position allowed the royalists to swiftly concentrate their various contingents for

mutual help in an emergency and, further, made it easier to supply their troops.

On the other hand, it was rather difficult for the patriot contingents, displaced and scattered as they were outside of

these important centers of population, to communicate rapidly and render assistance to each other in case of

danger, with the resulting possibility that each group of troops might be isolated and partially destroyed by the

strong enemy concentrations.

At the time of the breaking of the armistice (April 28, 1821), the General Headquarters of Bolívar were at

Barinas, while La Torre had transferred his center of operations from Valencia to San Carlos (155 miles from

Bolívar's headquarters).

The greater part of the Spanish Army was then organized into two strong divisions: one under General La

Torre at San Carlos and surrounding towns; and the other under his second-in-command, General José Tomás

Morales, quartered at Calabozo, El Sombrero and San José de Tiznados.

It was La Torre's plan to attack and destroy Bolívar at Barinas with his division amounting to about 3,500

to 4,000 men, before the patriot army of the Apure under the command of General José Antonio Páez was able to

join the forces of the Liberator, then inferior in numbers to those of La Torre. In execution of this plan La Torre

moved his army from San Carlos to Araure (about 40 miles to the south and only 115 miles from Barinas).

At the same time the Spanish General instructed General Morales, whose division was more or less equal

in numbers to his own, to deploy his troops to the south over the Apure Diver, to prevent the reunion of the Páez

forces with those of Bolívar at Barinas.

The patriots' positions upon the breaking of the armistice were as follows:

On the North, at Maracaibo, a division of about 1,500 to 2,000 men under the command of General Rafael

Urdaneta.

At Trujillo (on the west and about 180 miles south of Coro) a patriot garrison of about 500 veterans and

militia men-in-training under the Governor-General of that province, Colonel Cruz Carrillo.

At Mérida (about 120 to 130 miles southwest of Trujillo), a small group of recruits under the Governor-General of that province, Colonel Juan Antonio Paredes.

At Barinas, General Headquarters of the Liberator, some 2,500 to 3,000 troops were quartered.

At the Llanos (plains of Venezuela) in Achaguas beyond the Apure River, a division under the command

of General José Antonio Páez was stationed, totaling about 2,500 troops and including the British Legion.

And finally, in the eastern part of the country at Barcelona (a distance of more than 480 miles from the

Barinas General Headquarters), a group of veterans and recruits numbering about 1,500 to 1,700 men, under

General Juan Francisco Bermúdez.(2)

A part of this force was employed by Bermúdez in the siege of the fortified town of Cumaná (behind

Barcelona), which was defended by a Spanish garrison of some 900 men.

To the south of the Bermúdez headquarters, in the Guarico region of the plains, a cavalry contingent was

under the command of the patriot General Pedro Zaraza, and in the regions of the Aragua valleys on the high

plains, were the guerrillas of General José Tadeo Monagas (later President of Venezuela).

Also, on the Island of Margarita, off the eastern coast opposite Cumaná, were some native troops, plus a

small contingent of British soldiers of the English and D'Evereux corps, under the command of Lieutenant-General

Juan Bautista Arismendi.

All in all, the patriot forces could amount to some 9,000 to 11,000 men, scattered over great distances

outside the radius of the powerful royalist concentration, with the added difficulty of being unable to communicate

readily amongst themselves.

At the start of the hostilities, Phase One of the Liberator's general strategic plan consisted in carrying out

two divergent operations over the flanks and rear of the enemy-a maneuver which he had prepared beforehand

during the armistice.

General Bermúdez in the east was ordered to move his division swiftly and occupy Caracas. At Trujillo

Colonel Cruz Carrillo, who had received detailed instructions seven weeks before the end of the armistice, was

ordered to take the forces under his command, reinforced by those of Colonel Paredes at Mérida and the guerrillas

of Colonel Juan de los Reyes Vargas (totaling about 800 men), and occupy the cities of El Tocuyo and

Barquisimeto on the right flank of the enemy. After that he was to proceed to San Felipe and from there to threaten

Valencia and possibly Caracas.(3)

Both operations were carried out with complete success. General Bermúdez, after leaving some 500 men

in the siege of Cumaná, succeeded in occupying Caracas with the rest of his troops on May 14, 1821, and Colonel

Cruz Carrillo entered Barquisimeto on the 21st of the same month.

This sudden and opportune attack by Bermúdez, and his unexpected seizure of Caracas, compelled La

Torre to abandon his plans to attack Bolívar. Instead, he was forced to detach part of his best troops, among them

the second battalion of Valencey, and send them to help the Capital. Moreover, he ordered Morales to move his

division swiftly to the north against Bermúdez.

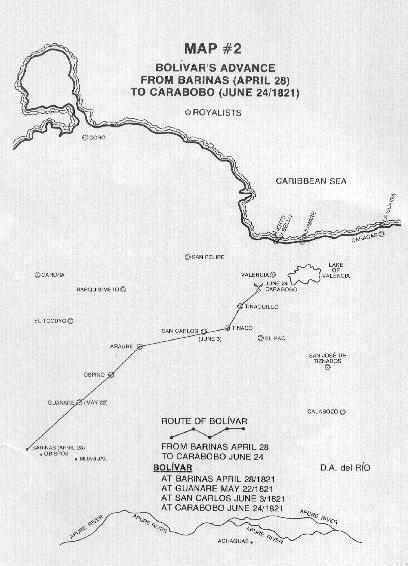

We shall now narrate Phase Two (See Map No. 2) of the daring strategy of the Liberator. On the same

April 28th (1821) he sent Colonel Juan Gómez from Barinas with a squadron of dragoons to "Boconó de Barinas",

compelling the enemy to fall back rapidly toward the north. Also, he sent Colonel Remigio Ramos toward Obispo

and Mijagual to the southeast of Barinas, to protect the movement of the Páez army in the north.

Fifteen days later, on May 13th, when Colonel Ambrosio Plaza succeeded in occupying Guanare, Bolívar

transferred his headquarters to that city, arriving there on May 22, 1821. Three days later, upon being informed

that both Caracas and Barquisimeto had fallen to the patriots and that La Torre had hastily vacated the cities of

Araure and San Carlos to help Caracas, the Liberator decided to transfer his headquarters to the latter city. On

June 2nd, San Carlos was occupied by the patriot troops under General Manuel Cedeño, and Bolívar arrived there

a day later. This advance to the north, and the transfer of his army from Barinas to San Carlos not only saved the

Urdaneta Division some 165 to 170 miles in its march from Coro to Barinas, but also allowed it to attack the

enemy, if necessary. At San Carlos Bolívar augmented his troops with the veterans of Cruz Carrillo, who

afterwards returned alone to Barquisimeto to assume command of the Maracaibo battalion (from the Urdaneta

Division) as well as other contingents from the region.

Meanwhile, General Páez, who had left his headquarters at Achaguas (beyond the Apure Diver) on May

10th, arrived at San Carlos with his forces, the vanguard on June 7th, and the rest of the troops four days later. The

Páez Division consisted of 1,000 infantry (which included the British Legion) and 1,500 cavalry. It took Páez one

month to move his troops the 280 miles between Achaguas and San Carlos because, following the instructions of

the Liberator, he had brought with him from the plains some 4,000 head of cattle to feed the army, and about 2,000

spare horses.

With these reinforcements, even before the Urdaneta Division arrived in San Carlos, Bolívar had available

some 6,000 troops, a number which at that stage was superior to the enemy forces. Eight days later, on June 19th,

the Urdaneta Division arrived with a contingent of 1,500 troops under the command of Colonel Antonio Rangel, as

Urdaneta had been compelled by illness to remain behind at Carora.

Between San Carlos and Carabobo (a distance of about 42 miles) there are two towns, El Tinaco (about 12

miles to the north) and Tinaquillo (18 miles further), the distance from Tinaquillo to Carabobo being about 12

miles.

On June 20th, the Liberator moved his troops toward El Tinaco. However, the day before, in order to

facilitate the free progress of his army toward Carabobo, he had sent Lieutenant-Colonel Laurencio Silva(4) toward

the town of Tinaquillo to dislodge an enemy reconnaissance platoon of 150 dragoons. Silva carried out this mission

with complete success, killing the commander and taking prisoner the rest of the platoon. The effect of this

skirmish was disastrous for La Torre, who made the mistake of evacuating the Buenavista hill, which gave him

control of the Carabobo approach, and falling back toward the north to the small hills facing the Royal Highway to

San Carlos.

On the eve of the Carabobo battle (June 23rd) Bolívar reviewed his troops in dress parade at the

Tinaquillo savannah (Taguanes), where eight years before, in 1813, he had achieved the most outstanding victory

of his "Admirable Campaign".

The Liberator had organized his army of 6,500 men into three Divisions:

The First, under General José Antonio Páez;

The Second, under Lieutenant-General Manuel Cedeño;

And the Third, under Colonel Antonio Plaza.(5)

Although the Liberator expected to concentrate some 10,000 men at San Carlos, this number was reduced

to only 6,500 by sickness, desertions and the fatigue of the troops caused by the long distances covered.

At the review Bolívar addressed the British Legion, saying, "Tomorrow you will see that the Colombians

are worthy of fighting side by side with the British". To the other troops he stated, "Tomorrow you will be

victorious at Carabobo".

An analysis of the divergent operations of Bermúdez and Carrillo, in carrying out the brilliant strategy of

the Liberator by attacking both the flanks and the rear of the enemy, makes the following conclusions evident:

1) It took the initiative away from the enemy.

2) It prevented the Spanish Army from following La Torre's plan to attack each isolated group of patriot

troops and thus prevent their concentration.

3) It permitted the uninterrupted march of the Urdaneta Division from Coro to Bolívar's Headquarters at

San Carlos, through territory controlled by the enemy. Bolívar considered the movement of the Urdaneta troops

over the Maracaibo-Coro-Barquisimeto route to be the most dangerous maneuver of the campaign.

4) It compelled La Torre to detach part of his troops to deal with the threat of Bermúdez and Carrillo, thus

weakening his forces on the eve of the battle.(6)

5) Bolívar succeeded in achieving the concentration of the patriot army, superior in numbers to that of the

enemy, and in advancing his General Headquarters some 160 to 170 miles to the north of his original plan, or from

Barinas in the south to San Carlos in the north. In the short space of fifty-two days, from April 28th to June 19th,

he had superbly carried out the reunion of all of his armies.

Phase Three of this masterful strategy is The Battle, where Bolívar's audacity and improvisation

complemented his carefully prepared "Plan of the Campaign" and resulted in his overwhelming victory.

The Battle

The Plains of Carabobo are a flat savannah sloping gently from north to south and measuring about one and a

quarter miles, with a length from east to west of slightly less than two miles.

The plains are situated about 7 miles southwest of the city of Valencia. Crossing the center of the

savannah are two roads; one leading from its right to the small town of El Pao on the southeast; and the other

going toward the left from Valencia to San Carlos. The towns of San Carlos and El Pao form the base of a triangle,

the apex of which is the town of Tinaquillo, some 12 miles south of Carabobo.

To the east of the plains runs the Paito River; to the north the Manzanas brook crosses the road to

Valencia; on the west the terrain rises to a high plateau, where steep ravines offering difficult access are

interspersed with small woods of scrub oak or tropical shrubs, which also extend toward the southwest among the

hills (spurs of the Andes). Through these narrow gorges run various brooks, the one nearest the plains being the

Carabobo rivulet.

The Royal Highway from San Carlos, after crossing the Carabobo brook, enters the savannah from the

southwestern end, up a slight incline some twenty yards high. At that time this road consisted of a narrow passage

or gorge among small hills.

The royalist army encamped at Carabobo consisted of some 4,000 men, of which 2,500 to 2,550 were

infantry, 1,650 cavalry, and the rest artillery.

One month before, on May 26, 1821, General Morales had succeeded in re-occupying Caracas (upon

Bermúdez's vacating it), and, after leaving some troops under Spanish Colonel José Pereira to pursue and destroy

Bermúdez, he returned to Carabobo with the rest of his forces, to join La Torre.

Anticipating that Bolívar's attack would come from the mountain pass which entered the plains through

the San Carlos Royal Highway, General La Torre had placed some of his contingents, including some artillery, on

the hills that towered above the road. Other troops were strategically deployed behind these forces on the San

Carlos-Valencia route to the northeast, covering also the road to El Pao. This plan allowed the various Spanish

battalions to assist each other in preventing the patriots from entering the savannah.

In reserve, he had placed 1,000 cavalry armed with carbines and lances in the rearguard, to protect the road

leading to Valencia. Actually, the position of La Torre was so formidable as to be considered virtually impregnable.

Bolívar, meanwhile, had mobilized his army at dawn on June 24th (the day of the battle), occupying the

Buenavista hill about three miles from Carabobo, where the troops had some food. For the purpose of studying the

enemy's position, Bolívar, with some of his general staff and four aides-de-camp, descended the narrow, rugged

gorge of the road to the vicinity of the Naipe brook, located about midway between Buenavista and Carabobo. Here

the Liberator climbed to the roof of a hut on the Naipe hill and observed through a spyglass the enemy's formidable

position defending the entrance to the plains, whereupon he put into action what we may call Phase Three of his

superb military tactics.

As the right flank of the royalists was protected by a series of hills and small woods of rough scrubby oak

which afforded an almost impassable natural barrier to the enemy, La Torre

had concentrated his attention on his front, leaving his right flank undefended. Bolívar decided to attack La Torre

from that side by using a neglected trail then known as "La Pica de la Mona" (The Monkey's Trail). This path

started from the left of the San Carlos road, before reaching the Naipe brook, and proceeded parallel to the plains

on the north but did not afford access to them. Therefore, it is most probable that the patriots' vanguard, after

proceeding halfway along the "La Mona Trail", may have turned off it to the right through the "Agua Dulce" brook

and through the gorge that ended at the Carabobo brook at the edge of the plains.

It was 9 A.M. when the patriots began moving from the Buenavista hill, while the sappers of the

engineers corps started to open a path through the thicket of "La Mona" for the march of the First Division under

General Páez. This flanking movement was executed by Páez with amazing speed in spite of the narrow and steep

gorges, where at times the troops were compelled to march single file.

When, rather late, La Torre became aware of the patriots' movement, he transferred one of his battalions

to cover the side from which the assault was coming. But he was unable to stop it. For, in spite of the deadly fire

that was thinning the ranks of the patriots, and after being repulsed twice, the battalion "Bravos de Apure"

succeeded in entering the plains. This was due to the timely help of the British Legion. This latter battalion, with a

contingent of some 340 men under the command of Colonel Thomas Ferrier, had climbed to the top of the plains at

the same time as the Apure soldiers. The British, many of whom were veterans of Waterloo, were able to stop the

enemy's fierce attack with a bayonet charge, but suffered the painful loss of one-third of their number, including

two of their commanders, Ferrier and Scott. After the battle Bolívar rewarded the British survivors with the Star of

the Liberators.

Behind the Páez Division Bolívar had rushed the Second Division to the ascent of the savannah, and one

of its battalions, "Tiradores" under the command of Colonel de las Heras, attacked the enemy from its left flank in

time for the Apure battalion to rally and force the royalists to retreat. Subsequently, the patriots' contingents were

reinforced by the First Squadron of the Honor Regiment of Páez. The fierce attack of this regiment of llaneros

(superb horsemen of the Venezuelan pampas), commanded by Colonel Cornelio Muñoz and by Páez himself, soon

put the royalist infantry to disorderly flight.

In an attempt to avoid this disaster, La Torre flung the bulk of his cavalry against the patriots. This force

comprised 1,000 llaneros who, having been for the previous ten years under the command of the dread and bloody

Asturian Boves, and now led by General Morales, had been victorious , with their fearsome lances, in one hundred

battles. But at Carabobo they were weary after so many years of fruitless struggle on the side of the Crown, and

their spiritless attack did not supply the Spanish infantry with the help they expected.

They were shattered by the furious attack of the "Escuadron Sagrado" of the Second Division which,

under the command of Colonel Francisco Aramendi, had just entered the savannah. However, the outstanding hero

of the battle was General Páez. Assembling a group of about 100 of his own llaneros (heroes of "Las Queseras del

Medio" and "Cojedes"), and followed by his general staff, he attacked the enemy cavalry with the intrepid daring

that, at this point, marked the start of the royalist rout. The Spanish mounted squadrons were put to flight along

the El Pao road, and entire infantry battalions surrendered and were taken prisoners.

The battle lasted scarcely two hours. The patriots had entered the plains (according to La Torre's official

communique) at 11:45 A.M. Two hours later the destruction of the best Spanish army in the Americas had been

accomplished.

However, La Torre, Morales and part of their general staff were able to escape under the protection of the

Valencey battalion. This battalion, consisting of about 1,000 troops under the command of Colonel Tomás Garcia,

had been placed in the southwestern part of the savannah, defending the San Carlos road to Valencia. Upon

realizing the Spanish defeat, the Valencey battalion rapidly retreated toward that latter city, preserving its ranks

with the most admirable discipline, at times forming quadres that successfully repulsed the sporadic attacks of the

pursuing patriots.

For this pursuit Bolívar utilized the infantry battalions "Rifles" and "Grenadiers of the Guard" by tandem-mounting them on the horses of a cavalry squadron. In spite of the furious onslaught of the patriots, which inflicted

casualties of about one-third of the Valencey's forces, the Spanish battalion continued its retreat with amazing

order and valor. The patriots were able to overtake the royalists on the outskirts of Valencia, but not until nightfall,

and then without success. The Spanish battalion swiftly crossed the city, encamped for the night at the foothills of

the coastal range, and reached Puerto Cabello on the following day.

The eminent historian Dr. Vicente Lecuna mentions that about 2,000 men succeeded in taking shelter

behind the fortifications of that port, including some 1,200 or more soldiers from the Tello and de Lorenzo

contingents who had escaped the pursuit of patriot Colonel Carrillo.

The royalist losses were estimated at about 3,000 men; half this number were taken prisoners, and some

1,000 to 1,200 were killed, wounded or dispersed. As for the patriot losses, although Bolívar in his official

communique on the battle mentions only 200 dead and wounded, it is more probable that their actual casualties

may have been over twice that figure, due to the deadly enemy fire against the republicans in their march through

the narrow gorges, and also to the fierce onslaught of the Spaniards trying to prevent their entry into the savannah.

The patriots suffered three regrettable losses among their commanders: General Manuel Cedeño,

Commander-in-Chief of the Second Division, who, in pursuit of the Valencey battalion, had reached the center of

the plains, where, oblivious of his high command, he charged the enemy ranks armed with a lance like an ordinary

soldier, and was shot in the head.

Colonel Ambrosio Plaza, Commanding General of the Third Division, also died like a hero. Bolívar

dispatched him with his forces to face the enemy positions on the front and to engage their attention while

Generals Páez and Cedeño entered the plains from their right flank. Upon reaching the savannah at the head of a

squadron and attacking the rearguard of the Valencey battalion, he was mortally wounded by an enemy bullet.

Another fallen hero was Lieutenant-Colonel Mellado,(7) who as second in command was riding next to

Colonel Juan José Rondón (the hero of Queseras del Medio and Pantano de Vargas), Commander of the First

Cavalry Regiment of La Guardia, Third Division. An anecdote tells that, upon attacking the royalists' left flank,

Rondón went ahead of Mellado, who exclaimed: "Ahead of me, only the head of my horse!" Fiercely spurring his

mount, he threw himself head long against the enemy bayonets, upon which his horse was impaled and perished,

while Mellado was struck by seven bullets and killed instantly.

As a reward to General Páez for the skill and bravery displayed by his division, chiefly responsible for the

superb victory, Bolívar, on behalf of Congress, promoted him on the battlefield to General-in-Chief of the Army.

In this small chronicle it would be rather voluminous to list the names of all the heroes who participated

in the battle. However, we would like to mention a few of them: Juan José Flores, subsequently the first President

of Ecuador; Juan Uslar, the Hanoverian who was formerly an officer under Wellington at Waterloo; Cruz Paredes,

who later distinguished himself at Pichincha and on the Peruvian battlefields; Bolívar's Aide-de-Camp, Lieutenant-Colonel Diego Ibarra, who was promoted to Colonel at Carabobo for his bravery in attacking the enemy at the side

of Colonel Plaza; and the officers Emigdio Briceño, Vicente Piñeres, Ramón Acevedo and Enrique Weir, all of

whom afterward became Generals.

Due to the condensed nature of these pages, we have omitted here the detailed description of the battle.(8)

The patriots occupied Valencia the same night (June 24th) and four days later, on the 28th, Bolívar made

his triumphal entry into Caracas with General Páez and their staffs. The Liberator was received with an explosion

of enthusiasm by the people, who hailed him as the "Father of his Country". While on his march to the capital,

Bolívar had dispatched several of his regiments to pursue the remnants of the enemy, as well as to defeat the forces

that had fled Caracas under the Spanish Colonel Pereira. At the same time, he ordered a siege of the Puerto

Cabello fortresses.

Two days after his arrival in Caracas, on June 30, 1821, the Liberator issued a Proclamation to its

inhabitants, which said in part:

"Caraqueños! A final victory has ended the war in Venezuela. There is only one fortress left to

surrender to us.(9)

"But peace, more glorious than victory, will soon give us possession of the fortresses, as well as

of the hearts of our enemies. Everything has been done to obtain Liberty, Glory and Peace; and

all of these we will have in the course of the year. "Caraqueños! The General Congress in its

wisdom has given you laws for your well-being. The Liberating Army in its military virtue has

returned your fatherland to you. Accordingly, you are now free

Caraqueños! Pay homage with your gratitude to the Priests of the Law, who from the Sanctuary

of justice have given you a code of Equality and Liberty...."

Bolívar

1. Field Marshal Miguel de la Torre, heroic defender of Zaragoza, had fought at Gerona and with

great distinction at Torres Vedras. At Salamanca he was promoted to Field Marshal, and at Vitoria he was in part

responsible for the final triumph that destroyed Napoleonic domination in Spain. La Torre replaced General

Morillo in the Supreme Command of the Spanish armies toward the end of 1820.

2. Lieutenant-General Juan Francisco Bermúdez was born at San José de Arescoar in 1782. In 1813

he was one of a small group of patriots that invaded Venezuela under the command of General Santiago Mariño.

Unfriendly to Bolívar, but later reconciled, he subdued various rebellions, in one of which he was killed in 1831.

3. Simultaneously, Bolívar had instructed General Arismendi at Margarita to disembark his troops

in the Curiepe or Ocumare coast, coordinating his operations with those of Bermúdez; he issued the same orders to

General Monagas in the Aragua valleys. At the same time, General Zaraza was to deploy his cavalry squadrons

over Calabozo, to divert the attention of Spanish General Morales and occupy the territory abandoned by the latter.

Commenting on these instructions, the eminent historian Dr. Vicente Lecuna wrote as follows: "None of the

Government's orders, except the march of Bermúdez, were obeyed in the east. The Margarita troops refused to

leave their island, and the two llanero chiefs (Zaraza and Monagas) did not mobilize their cavalry brigades."

4. Laurencio Silva, one of the heroes of "Queseras del Medio", was promoted to Colonel by Bolívar

at Carabobo. Three years later, in Bolívar's report on the Battle of Junín in Perú, Silva is mentioned as one of the

heroes of Junín, and at the Battle of Ayacucho (December 9, 1824) Silva was promoted to Brigadier-General, and

in 1828, at the Battle of Tarqui, to Lieutenant-General. He was at Bolívar's deathbed at Santa Marta and attended

his funeral. In Venezuela, during the Presidency of General Monagas, he defeated General Páez (his former chief),

taking him prisoner. In 1855, he was promoted to General-in-Chief, and was also Minister of War and Navy. He

died at Valencia in 1873, at the age of eighty-one.

5. Plaza had already been promoted to General by Congress, but had not yet been notified.

6. On June 20th, four days before Carabobo, Carrillo, who had been reinforced by the Maracaibo

battalion of the Urdaneta Division, and thus commanded some 1,500 men, had spread the rumor that his troops

were the vanguard of Urdaneta's, whose large contingents were marching behind him. La Torre, greatly alarmed by

this powerful menace to his right flank, made the mistake, two days before the battle, of sending Colonel Juan

Tello with 750 to 800 men to reinforce the troops of Spanish Lieutenant-General Manuel Lorenzo, who had been

defeated by Carrillo.

7. We have been unable to confirm whether this officer was the same hero who participated in the

battles of Pantano de Vargas and Boyacá: Juan Mellao. Secretary of War Briceño Méndez, in his official

communique on the battle dated June 26, 1821, mentions the loss of the brave Lieutenant Colonel Mellao,

Commander of the Dragoons of the Guard.

8. For those desiring a fuller account of the battle, we recommend reading the superb descriptions of

Carabobo by notable historians Santana, Lecuna, López Contreras and Bencomo Barrios.

9. The Puerto Cabello fortresses, then considered almost impregnable, were finally conquered two

years later, on November 8, 1823.

<< 9: Boyacá || 11: José María Córdoba >>