5: A Century of Peace

<< 4: Civil War || Bibliography

The Evolution of the Naval Squadron

Before the 1891 Civil War, the squadron had already been organized into a heavy

division, formed by the ironclads, and a "lighter" division made up of the

cruiser Esmeralda and the corvettes. Once the Civil War was over the

cruisers being built for Chile in France were delivered. These were the Errazuriz

and the Pinto. In 1894 the Esmeralda was sold to Japan.

Under the name Idzumi she would have the honor of being the first ship to

sight the Russian Squadron at battle of Tsu-Shima in May 1905. It was replaced by a new Esmeralda

which arrived in Chile in 1898. The new ship served as flagship for a cruiser group that

was designated as the "Squadron of Evolutions", the first all cruiser squadron

in the Southern Hemisphere. It was made up by a powerful array of ships:

Cruisers of the Squadron of Evolutions

| Name |

Year |

Tonnage |

Speed |

| Pinto |

1892 |

2,100 |

17 |

| Errazuriz |

1891 |

2,100 |

17 |

| Blanco Encalada |

1894 |

4,500 |

22,7 |

| Zenteno |

1897 |

3,400 |

20,2 |

| Esmeralda |

1898 |

7,000 |

23 |

| O'Higgins |

1898 |

8,250 |

21,5 |

| Chacabuco |

1902 |

4,500 |

22,5 |

The heavy division soon became a coastal defense squadron. It was composed of the Huascar,

Cochrane, and by the new battleship Prat. This ship was

actually the second ship to bear the name of Iquique's hero. The first Prat

could not be delivered to Chile because it was finished before the War of the Pacific was

over and was, therefore, sold to Japan where it was re-named Itsukutchi.

The second ship was finished in 1890 and was armed with four 9.4 inch guns, mounted in

turrets with electric controls and protected by a 12 inch armor belt. It was rated at 18

knots speed but could not keep up with the cruisers.

A third division was composed of the torpedo chasers and destroyers led by the very

fast Thompson, capable of 30 knots, built by Yarrow. In the Straits of

Magellan served a small torpedo boat flotilla, supported by tenders and auxiliary craft.

The entire squadron had 4,425 officers and men, with an additional 1,100 personnel in

training. Another 530 men were working on surveying projects deep in the southern

archipelago.

This new dimension required a new administrative structure. Captain Montt, now promoted

to rear admiral, was elected President of Chile after the Civil War. When his term expired

he returned to the Navy and assumed command of all naval forces, under the title of

Director General. Under Montt the Navy established a solid basis upon which future growth

could rest. Schools of Artillery and Engineering were created and the school ship Baquedano

was purchased in England to train the men. Soon, Chilean midshipmen and apprentice seamen

were sailing the seven seas and visiting the five continents. The ship was rigged as a

corvette with an auxiliary steam plant and engine. The combination made her a slow and

difficult sailer, which unintentionally gave the Chilean crews the best training they

could possible get.

The expansion plans of the Navy were curtailed by the May Treaties signed with

Argentina in 1902. Although the disarmament pact allowed for delivery of the cruiser Chacabuco

and three destroyers, it was necessary to sell two powerful battleships destined to

replace the ironclads. These were the Constitucion and Libertad,

splendid ships of 12,000 tons, 10 inch guns and capable of 19 knots which were being

completed by Yarrow. They became HMS Triumph and HMS Swiftsure.

In February 1907, Teddy Roosevelt's Great White Fleet arrived in Punta Arenas under the

command of Robley D. Evans. He was received enthusiastically and entertained at banquets

and balls. Evans was hesitant to take Chilean pilots for the final leg of the passage with

his 16 battleships, so he had them follow the Chacabuco whose orders were

passed with speed and accuracy. By night fall the whole fleet was in sight of the open

seas. Although Evans' orders did not include a visit to Valparaíso he decided to alter

course at least, to come into sight of the port and reciprocate in part, for the piloting

services of the Chacabuco. The gun salvos of the fleet reverberated

against the hills of Valparaíso in a salute that the city would never receive again. On

the heights 2000 Chilean sailors spelled the word "Welcome".

In 1910 the Chilean Congress passed on law which, in commemoration of the First

Centenary of Chile's Independence, ordered the construction of two battleships, six

destroyers and two submarines. But the outbreak of World War I in 1914 delayed the

delivery of these ships. The two battleships, still under construction, were purchased by

the British Navy . One battleship was almost finished and it became HMS Canada.

She was the only 14 inch gun battleship at Jutland. She was eventually returned to Chile

and as the Latorre served as flagship of the squadron. The other ship,

whose original name was Cochrane, was commissioned as the aircraft

carrier HMS Eagle she ended her days as the victim of a German torpedo

during WWII. Only two of the destroyers were delivered. The other four served in the

British Navy and the GoZi under the name Tipperary was

sunk by German gunfire at Jutland. The two submarines under construction in Seattle,

Washington, were sold to Canada.

In part payment for retention of Chilean ships in British shipyards, England ceded to

Chile six submarines which were being built in the United States. These were "H"

type boats, only 335 tons each and designed for coastal defense rather than the open seas.

Chilean crews took them over in Boston and after a short training period sailed them to

Valparaíso. This long cruise served to prove the capabilities of submarines for extended

patrols. Until then, submarine raids had been limited in length; this trip without

difficulties by inexperienced crews dissipated doubts about their endurance and ability to

sustain the crews for long periods of time.

On November 1, 1914, the German Pacific Cruiser squadron met the British off Coronel,

within 50 miles of the Chilean coast. Under the capable direction of Admiral Von Spee, the

Germans sank the flagship Good Hope and the cruiser Monmouth

before the British retired under cover of darkness. Von Spee made a triumphal entrance in

Valparaíso with his five ship squadron but, when he tried to enter the Atlantic, he was

defeated by a British squadron off the Falkland Islands. Only one ship escaped, the

cruiser Dresden. The Dresden took refuge in the Juan

Fernández Islands but there she was found by the protected cruiser Glasgow

which opened fire at close range disregarding Chilean neutrality. The Dresden's

Captain ordered the crew to scuttle the ship.

In 1919 one of the H submarines, the Rucumilla sank in Talcahuano Bay.

Thanks to very intelligent action by her Captain, Commander Aristides del Solar, quick

reaction by Commander Enrique Errazuriz, Captain of the tender Contreras,

and the skill of the Talcahuano shipyard workers, it was possible to save her entire crew.

Errazuriz, a submariner himself, thought that the boat had not dived properly and when he

observed bubbles coming to the surface, he ordered the spot to be marked with a buoy and

simultaneously signalled the command post that something was wrong. These events took

place at 0900 hours. A 180 ton floating crane was towed to the site; divers from the

Torpedo school located the submarine, connected a telephone buoy; and passed chains under

the keel of the sunken sub. In the meantime Commander Del Solar ordered his whole crew

into the central compartment of the submarine. Realizing he could not surface, he

conserved the air in the tanks, which he bled periodically into the submarine, thus saving

his crew. One of the tugs towing the crane accidentally cut the telephone line and it

proved impossible to connect it again. At about 1300 the bow of the submarine surfaced but

at that critical moment one of the chains broke and it was necessary to lower the sub to

the bottom. The boat was under 16 meters of water, with the forward and rear compartments

full of water which added another 300 tons to its original weight. The divers went back to

work and this time steel cables were passed to reinforce the chains. During the second

effort one of the wires in the steel cables parted. Just then a volunteer appeared and he

climbed through the crane structure, knowing that if the rest of the cable gave out he

would be crushed. Hanging precariously from the chains and cables, the man did a perfect

repair job. Thanks to his effort it was possible to continue lifting and at 1700 the deck

of the Rucumilla was above water and the crew was able to breathe fresh

air. The volunteer turned out to be a Navy deserter, Eucarpio Muñoz, who decided that was

how he would try to make up for his breach of discipline. Much has been written about this

incident, but above all, mention should be made that the crew of the Rucumilla

remained under control at all times; they showed bravery, patience and discipline; they

never uttered a curse or a complaint during eight hours of almost total darkness, cold

water up to their knees; breathing nauseating gases from the batteries. Knowledgeable

foreign authors without exception consider the salvage of the Rucumilla

one of the most successful submarine salvages in history.

These small submarines served for many years and later the submarine service was

augmented by three large "O" type units built in England and also a submarine

tender, the Araucano. In 1961 the Navy received two "Balao"

class submarines, Thomson and Simpson, from the United

States. A submarine school provides rigorous training for the underwater service, while

the shipyard at Talcahuano has developed the capability to make major repairs to its Oberon

class and "Type-209" submarines.

In 1929 the Latorre returned from England where it underwent a thorough overhaul and

modernization. As part of the renovating program several auxiliaries, three large type

"O" submarines and six Serrano class destroyers were acquired.

These ships had first-rate sea conditions, they all exceeded their rated speeds during

trials, and gave excellent service for many years. All these units purchased before 1930

were adequate for the period naval service of the country and defense of maritime

communications. But the severe measures taken during the 1930's to alleviate the crisis of

the Great Depression prevented the Navy from renovating this valuable materiel, until

after the Second World War. One exception was the sailing vessel Priwall,

a beautiful ship of the German "P" Line which was donated to the Navy during

WWII and became a schoolship replacing the old Baquedano, under the name Lautaro.

The Lautaro was reconditioned at Alameda Navy Yard in California

during the Second World War and returned to Chile where she became a valuable training

unit. On February 28,1945, this ship was sailing off the coast of Peru, en route to Mexico

with a cargo of nitrate. In midmorning a small fire suddenly ignited her cargo. Two of the

four masts came down in thunderous explosions and in a few hours, the Lautaro

had been reduced to a smoking hulk in which 21 of her crew perished, including her second

in command, Lieutenant Commander Enrique García, several officers and the ship's bosum.

Luckily a distress signal had been sent and received and it was possible to rescue the

rest of the crew though the ship sunk while under tow.

After the war the squadron was augmented by the Brooklyn class

cruisers Prat (ex Nashville) and O'Higgins,

(ex Brooklyn), six antisubmarine vessels and several landing craft. Three

transports were also acquired. But it would not be until 1960, before the first warship

expressly built for Chile in 30 years would arrive. The destroyer Williams

was soon joined by her sister ship Riveros. The old Serrano

class destroyers were decommissioned and replaced by two "Fletcher" class ships

which bore the names Blanco Encalada and Cochrane. The

old Latorre was sold as scrap to Japan and the squadron was greatly

reduced in tonnage although its armament was modernized. Two larget destroyers were

acquired from the United States, the "Sumner" class, destroyers Zenteno

and Portales. Continuing the torpedo boat tradition, four

"Jaguar" type fast boats were acquired in 1964 and a new Latorre

joined the squadron in 1972. She was the former Swedish cruiser Gota Lejon.

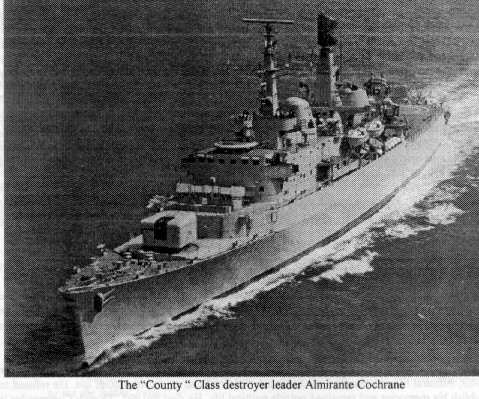

Chile's naval squadron has been incremented with four "County" class guided

missile cruisers, renamed Prat, Cochrane, Blaco Encalada and Latorre;

and four "Leander " class frigates, Lynch, Baquedano, Zenteno

and Condell. In addition two "Reshev" class guided missiles

patrol boats, several landings crafts, and approximately thirty auxiliary vessels make up

the Chilean Navy in 1993.

Naval aviation in Chile is as old as military aviation. The first naval pilots

completed their courses at the Army Air Base, El Bosque, in 1916. In 1916 England

delivered ten planes for the Navy as part of the compensation for keeping the Chilean

ships. These first ten planes became the Fleet Air Arm. In 1921 a naval/air base was

established in Valparaíso but a year later it was moved to Quintero under the command of

Lieutenant Commander Edgardo von Schroeders. Two bases were established later, one in

Chamiza near Puerto Montt and the other at Bahia Catalina, near Punta Arenas. In 1930

these units were unified to form the Chilean Air Force. The Navy turned over a small but

efficient, enthusiastic, and disciplined force with well established bases.

But the Navy never abandoned the basic and fundamental principles of naval aviation and

Navy personnel continued to be trained as pilots, mechanics and maintenance personnel and

some were sent to study at US Navy installations. The Navy was able to maintain the idea

that a naval air force with it own materiel and personnel was an absolute requirement for

an efficient and capable naval force.

In 1953 the naval air arm was re-established and helicopters, transports and training

planes were acquired. A naval air base was set up at El Belloto and a training program in

anti-submarine warfare (ASW) was carried out, while at the same time an air photography

service was set up to assist in updating nautical charts of territorial waters.

The Chilean Marine Corps is an institution whose history starts with the Navy's. In

fact when the Aguila put out to sea on her first trip, on O'Higgins'

orders, twenty -five well armed infantrymen were on board. These were Chile's first

marines. During the War of Independence, landing forces, organized as marines and under

the command of British trained marine officers, served in all ships of the squadron and

made landings on the coast of the Americas from Chiloe to California. Men such as

J.M.Charles, William Miller, Jorge Beaucheff, George Campbell and Richard L. Vowell, led

the marines on their road to glory at Pisco, Valdivia, Arica, Ancud, and San José del

Cabo.

During the Chilean expansion period the marines did not have a separate or permanent

organization. The artillery for example, operated under command of the Army with Army

officers. Under that label, we find them at the capture of Santa Cruz' squadron, at

Callao, at Casma, in the construction of Fort Bulnes and at Abtao. Since their mission was

to cover the garrisons of the coastal fortifications they served in forts at Valparaíso,

Talcahuano, Lota, Coronel, and Ancud.

This powerful arm did not participate in strength during the War of the Pacific. The

strength of the naval artillery was increased to 1200 men and divided into two battalions

with four companies each under Army officers. These soldiers were distributed among the

squadron's ships and served throughout the war. At Iquique, Marine Sargent Aldea boarded

the Huascar with Captain Arturo Prat, and in the landing at Pisagua a 670

men Army battalion led the way up the cliff.

Once the war was over, the previous weak organization returned and the name was even

limited to Coast Artillery. But the Corps acquire great importance with the installation

of powerful fortifications at Valparaíso and Talcahuano. The most select troops of the

Army were sent to cover the garrisons. In 1903 these troops were placed under Navy command

as Marine Artillery; and until 1938, they were concentrated in two regiments of one each

at Valparaíso and Talcahuano.

New developments in artillery, specially fire control techniques using radar,

anti-aircraft missiles, and abandonment of coast artillery, forced a reorganization of the

Corps. In 1964 it was officially named Cuerpo de Infanteria de Marina,

(Marine Infantry Corps). Four battalions were created, one each stationed at Iquique,

Valparaíso, Talcahuano and Punta Arenas. The Marine School, located at Fort Vergara in

Viña del Mar, was created in 1897.

In spite of its somewhat fragmented history, the Chilean Marine Corps has developed a

tradition of loyalty, devotion to duty and patriotism, which received a very interested

backhanded in 1973. In one of the secret documents of the Marxists, the following note was

found:

" It must be kept in mind that the marine infantry does not have any of our

elements within their forces, for this reason her forces must be neutralized as soon as

possible by units loyal to the plan. " (9)

At present the Chilean squadron maintains an active fire support and antisubmarine

warfare group, a small submarine flotilla, and a squadron of torpedo and missile boats. It

is going through a modernization stage that looks at the future, searching for the best

available materiel and highest training of its personnel in order to serve Chile better.

THE NAVAL MUTINY OF 1931

In 1931 the Great Depression was having its effects on Chile. The country was suffering

from a serious economic and political crisis of a magnitude that the nation had never

experienced before. Two presidents had resigned and the executive power was resting

temporarily on the President of the Supreme Court.

As usual, the squadron had sailed north for the winter where a rigorous training

program was scheduled. During this period, the squadron was divided into two divisions,

the "Active Squadron" and the "Instruction Squadron". On board the Latorre,

flagship of the Instruction Squadron , were 21 men who had been given the temporary rank

of "corporals" in the Supply Branch. These men had not gone through the

traditional naval training that started at age fifteen, but had been hired so that they

could be trained on accounting methods and eventually become "accounting

assistants" to regular supply officers. Some of these men were experienced union

organizers or political agitators who had managed to hide their past and had achieved high

scores in the competitive examinations.

The difficult economic situation affected the naval personnel in a way that the rest of

the country could not possibly know. Their families had been left behind in Valparaíso

and Talcahuano and their small salaries did little to comfort the prolonged absence from

their homes. The government in Santiago had announced a 30% reduction in salaries to all

government employees, including the Armed Forces.

The supply corporals, led by one Manuel Astica suggested that the crews present the

Squadron's commodore with a List of Petitions, a standard practice in Chilean factories,

mines and nitrate works. When Captain Alberto Hozven learned that these demands were

circulating among the crew, he ordered that a delegation from each ship in the squadron

attend a formation on the decks of his flagship. There, in a hard and authoritarian way,

he informed them that this type of polticking was anti-patriotic and contrary to navy

traditions and regulations. He also stated very clearly what procedures the navy used in

case the crew wanted to make a request.

The speech by the commodore did not calm the crews. It fell instead, like a bad seed,

on the well prepared minds of the petty officers who had been lectured by Astica and his

associate Agustin Zagal. The majority of the sargents wanted to forget the list of

demands, but Astica and Zagal insisted on the crew's right to make demands. The petty

officers of the battleship met, and after an passionate speech by Astica, decided to take

over the ships.

That night, 1 September 1931, the officers on duty in the flagships O'Higgins

and Latorre were captured and all officers locked in their cabins.

Similar actions took place in all the ships anchored in Coquimbo. The petty officers in

the flagship assumed control of the squadron appointing themselves "General Staff of

the Crews" (Estado Mayor de las Tripulaciones). Astica played an important role in

all this and was elected "Secretary " of the governing body.

The government took contradictory measures. On the one side, it decided to deal with

the crews by sending Rear Admiral Edgardo Von Schroeders to Coquimbo. On the other hand ,

it rejected the temporary agreements that the Admiral had reached with the leaders of the

rebellion. The navy was not allowed to solve what was began as an internal problem. The

solution proposed by the Admiral and which had been accepted by the majority of the petty

officers, who were, after all, career men with many years in the service, would have

solved the rebellion and identify the real leaders of the mutiny.

Unfortunately, political elements attempted to take advantage of the situation. This

situation deteriorated rapidly as the naval bases at Talcahuano, the Southern squadron ,

the Air Force base at Quintero and the Salinas naval complex, near Valparaíso, joined the

revolt. The rebels, now under the control of the "Estado Mayor de

Tripulaciones", changed their demands and called for, among other things, a social

revolution. Since no agreement could please the government, it was decided to put down the

revolt by force. The Talcahuano base was attacked by two army regiments and a company of

navy officers and was captured after a short fight. Salinas was similarly occupied by the

government forces without serious resistence. Finally, the squadron at Coquimbo was

attacked by the Chilean Air Force.

The air attack on the squadron, in spite of being carried out with bravery and daring,

was a military failure. However, it served to convince the crews that they had no support

in the rest of the country, which Astica and his cronies had convinced them they had. Next

morning the destroyers notified the Latorre that they would no longer

obey their orders. The officers were restored and ship after ship returned to the control

of their commanding officers. Aboard the Latorre , Astica's masterful

oratory went for naught. The crews demanded that their officers be restored and landed the

leaders at Tongoy.

The revolt ended with the surrender of the squadron at Coquimbo. The results could have

been tragic. Mistakes had been made by the navy: those untrained men should have never

been allowed on board a warship without a thorough screening. The government should have

allowed the navy to solve her own problems.

The results of this events were perplexing. Many officers were dismissed from the navy,

as well as all the ship captains who lost their commands. The true culprits, after a long

process, and a change in government, were pardoned and soon were out in the streets. Even,

Astica was not only set free, but in due course, the government paid its share towards his

retirement. It was a hard lesson, no doubt, for those who think that professional naval

forces can keep themselves totally isolated from politics.

PEACETIME ACTIVITIES

In peacetime, the first responsibility of the Navy is to be prepared for war. Of these

the most important is training. Few Chilean institutions maintain so many educational

centers in proportion to their budget, as the Navy. All Navy personnel must go through

either of two basic schools:"Escuela de Grumetes" (Seamen's school) for enlisted

personnel and the "Escuela Naval" (Naval Academy) for officers.

The Escuela de Grumetes prepares enlisted personnel for the Navy through a two year

training program and several selection processes. Many Navy officers started their careers

there and received their commissions after further training at the Escuela Naval for

officer training. The school was founded in 1868 and for a while its development was

somewhat irregular, changing its location and varying the number of students until the

turn of the century when the sailing ship Majestic was purchased. On

board this vessel, re-named Lautaro, apprentice seamen learned valuable

lessons before going into the squadron. In 1921 the school was re-established on

Quiriquina Island, at the mouth of Concepcíon Bay six miles from Talcahuano. Today it

bears the name of Captain Alejandro Navarrete, the first 'sea officer' of the Navy, who

enlisted as a cabinboy in 1893 and "going through the hawse hole" earned his

commission retiring as captain in 1933.

The Escuela Naval, which bears the name of its most distinguished graduate, Commander

Arturo Prat, prepares executive officers for the Navy, Marines, Supply Corps, and Merchant

Marine. It enjoys an international reputation and its alumni include many foreign

officers.

A second stage of this basic education is taken the year after graduation, when the

graduating classes of the two schools form the crew of the training ship Esmeralda.

The midshipmen and apprentice seamen take a long cruise through either the Pacific or

Atlantic Ocean, visit different countries, learn about life at sea and above all operate a

sailing ship under different sea and weather conditions.(10)

The Navy maintains several schools where a second educational cycle is offered.

Usually, a Chilean mariner would complete his training cruise and serve for a two-year

period in a unit of the squadron or in the ships serving in the southern channels or

Antartica. Once this is completed, he may be selected to enter advanced schools, such as

Armaments, Engineering and Operations, which are located in Salinas Naval Base, just north

of Valparaíso. Other schools are Submarines, Supply and Services, Health, and a separate

school to which civilian students are admitted, Naval Artisans, which prepares the workers

for the Navy yards. The Navy also trains some of its personnel in other schools of the

Armed Forces, such as musicians. Chilean naval personnel have attended military as well as

civilian colleges and universities in the United States and Europe. An American writer,

already quoted, Robert Schiena, says:" The Chilean sailor is among the best trained

in the world."

The "Academia de Guerra Naval", Naval War College, is a prestigious

institution founded in 1911, making it the oldest War Academy in Latin America. The

motivating force behind its organization was Admiral Patricio Lynch who felt that a major

shortcoming of the War of the Pacific was the lack of officers qualified for General Staff

work. Lynch however, would not live to see his plans brought to reality. For the first few

years it was directed by Captain Charles Burns of the Royal Navy. It is located in

Valparaíso .

Together with the universities and the "liceos" (high schools), the Navy has

been one of the Chilean institutions that has helped breakdown social barriers. The two

basic schools admit students only on merit, without consideration of financial or social

status. All conditions being equal, preference is however given to candidates who are the

sons of Armed Forces personnel, without distinction as to rank or branch of the service.

The Navy also maintains an aggressive program to promote enlisted men to officer training

courses. Those selected enroll in special courses at the "Escuela Naval."

Many of the courses are offered at these service schools are not strictly limited to a

Navy career. Many of the artisans, electricians, engineers, accountants, mechanics, etc.,

after being educated at the Navy schools, enter private industry or government service.

Navy trained engineers, for example, can be found in the steel, petroleum, and mining

industries.

A second duty of the Chilean Navy, no less important than training, is the development

of the sparsely populated areas of the country. The Navy not only explored, charted, and

established posts in isolated and far way regions but, it assists, transports and supplies

homesteaders and pioneers in regions where the comforts of civilization are unavailable.

There are many small settlements in the Magellanic Channels that depend exclusively on the

Navy for their existence. The Navy maintains outposts in remote places such as the mouth

of the Baker River, in Yelcho, Palena, and elsewhere. These outposts have health

facilities, supply stores and radio stations. The Navy provides regular transport service

for supplies, fuel and mail, and it carries the products of the remote areas to commercial

centers for very modest prices.

At Navarino Island for example, the Navy founded Puerto Williams in 1959. The small

village with schools, hospital , and other facilities, soon attracted settlers and today,

besides serving the Navy as a supply depot for Antartic Operations, it is the southernmost

town in the World.

Easter Island is another example of Navy colonization. The island was discovered in

1722 by the Dutch navigator Roggoveen. Adventurer after adventurer tried to exploit the

natives in any which way possible, including selling off part of the male population as

slaves to the guano works of Peru. In 1866 the Abtao, with a midshipman

class on board, stopped at the Island. One of the instructors was Lieutenant Commander

Policarpo Toro, who took a special interest in the island, not for the ancient monuments

to be found there, but also because of the wretched condition of the inhabitants. Toro

wrote an extensive report to his superiors, suggesting that the island should be protected

by Chile's national flag. President Balmaceda took notice the report and ordered Toro to

investigate the possibility of annexing the Island. Toro travelled to Tahiti in a small

schooner, purchased the real estate on the island owned by Frenchmen then residing in

Tahiti, and on September 9, 1888, took possession of the Island for Chile. A small colony

of 12 Chileans was established.

Unfortunately the Civil War and other matters distracted the government's and Navy's

attention. Some of the payments were not paid when due and Commander Toro was sued by the

Island's former owners. Toro paid them by mortgaging his own salary and house, while the

government gave away the right to exploit the Island to a private company. Only in 1917

was the Island placed under the authority and government of the Navy. Although naval

administration proved to be effective, progressive, and just, commercial exploitation

continued under private companies. It was not until 1966 that the colony became an

integral part of Chile by being made a Department of the Province of Valparaíso. The Navy

had much to show for its administration: schools were created; a hospital established,

including a leper colony; water and electricity provided; roads built; a small pier

erected ; and in general, the same services were provided as for continental outposts.

The Navy stands ready to assist in case of natural disasters. In 1906, after the great

Valparaíso earthquake the squadron landed men and rapidly provided help for the victims.

Sailors acted as firemen, patrolled the streets and set up soup kitchens and first-aid

posts. The Navy even assumed temporary governmental authority. Similar services were

provided in the 1939 earthquake which destroyed Concepcíon, even though the Talcahuano

Naval base was also hard hit. In the great earthquake and tidal wave of 1960, the Navy

took on the mission of helping and moving the population of small coastal towns and

villages between Talcahuano and Chiloe. Ships were distributed along the coast and as soon

as they anchored, sanitary and construction parties were landed which provided not only

the most elementary help and assisted with hand labor but also re-established

communications, set up emergency water supplies, and even brought people on board to sleep

when no other shelter was available. For the first time Navy helicopters operated deep

inland assisting in rescue and salvage operations. Later, the Navy cooperated in

reconstruction work; but the tidal wave caused such profound changes in the hydrographic

configuration of the zone that it was necessary to confirm charts, as well as to replace

and add buoys, navigation beacons, and even light houses. In these tasks the helicopters

provided invaluable assistance. Similars tasks were performed after the March 1985

earthquake.

In many instances the Navy has had to provide the services normally assigned to the

merchant marine. Warships were used to transport food supplies, merchandise, and civilian

passengers after the 1960 earthquake and tidal wave which proved devastating to many of

the small shipping companies in the southern area.

In 1946 Chile took a big step in the Antartic. Although the country had asserted rights

in the continent that went as far back as colonial times, the limits of the Chilean

quadrant had not been defined until 1940 and no effort had been made to establish an

outpost in the area. In December 1945 the transport Angamos and the

frigate Iquique departed Punta Arenas in a mission similar to the one

which a century before had been given to Guillermos and the Ancud:

explore, chart, and establish an outpost that would physically confirm Chilean sovereignty

over the land. The Navy constructed a small base on Greenwich Island and a meteorological,

scientific, and observation station was set up. It was almost an entirely Navy operation.

In the following years other bases were built. Chile is a signer of the Antartic Treaty

and in strict observance of its terms, the Chilean Navy and the Armed Forces maintain only

peaceful activities in the frozen continent.

A traditional role of the Navy has been assistance to navigators. Coast guard type

activities are provided by the Navy under The General Directorate of the Maritime

Territory and Merchant Marine. These services have been in operation for more than a

century. A large percentage of Navy personnel is engaged in duties of this nature. The

Navy provides meterological services, radio stations and observation outposts, buoys,

beacons and light houses. In addition every Navy ship is ready to rescue, lend assistance

to shipwreck sailors or to help salvage vessels. Many ships have been lost in salvage

operations. The steamer María Isabel sank in 1857, after hitting a rock

during the rescue operation of the Sardinian ship San Giorgio in the

Straits. In 1905 the cruiser Pinto sank under similar conditions in the

Chiloe channels. The transport Valdivia ran aground and was lost while

attempting rescue operations in Taitao peninsula. The tender Janequeo

sank in 1965 with the loss of 53 men and her captain, while attempting to tow the Leucoton,

which had been driven aground by one of the worst storms ever to hit the coast of Chiloe.

During the salvage operations Seaman Mario Fuentealba rescued two drowning sailors and was

himself lost while attempting to rescue a third. A similarly heroic performance was that

of Corporal Leopoldo Odger, who though badly wounded in his face, managed to save three

lives before losing his own.

But the three most spectacular rescues performed by the Navy took place in Antartic

waters. In August 1916, Lieutenant Luis A. Pardo, commanding the tender Yelcho,

left Punta Arenas in an attempt to rescue the men of the Shackleton South Pole expedition,

which had been abandoned at Elephant Island. Shackleton had crossed the Drake Passage in a

small boat and had twice attempted to reach his companions. Pardo led his ship without

mishap through the Drake Passage in the mist a strong winter storm. He found the island

covered by fog but free from icebergs. Pardo decided to approach the island, confident of

his crew, relying on the echo he could hear from his own ship's siren and trusting his own

instinct. When the fog cleared the ship was found to be half a mile from the camp. That

very afternoon Shackleton's men were embarked and the ship started her return voyage to

Punta Arenas. Pardo's feat is the most spectacular rescue ever performed by the Chilean

Navy when one considers the limited resources at his disposal."These Chilans--wrote

Worsley, one of Shackleton's lieutenants--are by far the finest seamen in South America.

Probably they are the best Latin sailors in the world."

Twice the Navy has conducted rescue operations on Deception Island. On December 4,

1967, the ship Piloto Pardo was departing the island, when the land was

shaken by a violent volcanic explosion. From nine miles away the crew of the Pardo

observed an enormous column of smoke that rose to 2000 meters and covered one third of the

island where three bases are located. The Pardo returned immediately to

rescue the men at the Argentinian, British and Chilean bases. When the ship arrived at the

entrance of the inner bay the cloud was 10,000 meters high and completely covered the

island. The air was thick with ashes, flying rocks, smoke; and other thick gases; and it

was thought that no one had survived. But radio contact was established and the men from

the Chilean base were ordered to the British base from where a rescue would be attempted.

It was impossible to approach land. The interior of the bay was boiling, wind was blowing

at 40 miles an hour, and continuous explosions rained mud and stones on the sea.

That night the ship remained off the island under constant discharges of rocks and

ashes that soon covered the deck. The mushroom cloud over the island provoked an electric

storm that prevented radio communications, but at dawn a weak signal was received saying

that the Chileans were at the British base. At three in the morning orders were given to

proceed with the rescue operation. The only means of transportation were Naval Aviation

helicopters because the tides oscillated between two and three meters range. Unable to

maintain radio contact, the aircraft disappeared in the cloud and managed to rescue 42 men

who had almost given up any hope of being saved. The ship went around the island at full

speed to assist in the rescue of the Argentinians who had been unable to reach the

designated spot.

Two years later, in February, 1969 the Pardo again received a distress

call, this time from HMS Shackleton. The British base at Deception had

been destroyed again by volcanic eruptions and the men were walking towards the southern

tip of the island. The Pardo approached the island in heavy seas, strong

winds and thick smoke. Flying under very adverse conditions, such as smoke and flying mud

and rocks, the helicopters managed to land and rescue the men who were later transferred

to HMS Shackleton.

In 1972 a distress message was received from the tourist ship Lindbad Explorer

which had ran aground on King George Island. The Yelcho and Pardo

responded. Helicopters were launched and the Yelcho approached the

stranded ship with the intention of taking her under tow. The Pardo received

154 passengers but had to remain at anchor waiting for favorable weather before it could

sail to Punta Arenas.

The construction of lighthouses along the rugged coast of Chile is an enterprise that

deserves a better historical coverage. The Evangelistas lighthouse is located in a remote,

inaccessible island, always under difficult weather conditions. It was designed and built

by a civil engineer, Jorge Slight. This lighthouse, which marks the entrance to the

Straits of Magellan from the Pacific, is a masterpiece of Chilean engineering. In order to

carry the materials to the rock on which the tower was to be built it was necessary to

build some costly and difficult structures. The weather was so bad that the construction

were thought to be impossible. The place is lonely, whipped by strong winds and rarely

does calm weather last for more than a few hours at a time. The ships that resupply it

wait in a bay called Forty Days because that is how long a tender once had to wait before

it could approach the rock on a supply mission. Similar problems were found in the

construction of other light houses. Supplying or refueling these beacons is still not an

easy job, although the helicopter has proven to be a marvelous aid in this work.

No less important has been the enormous effort devoted to hydrography. For more than a

century the Navy has explored, investigated, charted, surveyed and resurveyed its charts.

Today the whole coast and a good portion of the Chilean Antartic area have been properly

covered. Chilean charts have a reputation for accuracy, clarity, and currency.

THE DEFENSE OF INTERNAL LAW AND ORDER

Ever since its founding the Navy had maintained a tradition of discipline that had

seldom been broken. The fact that it performed its duty away from political environments,

that its officers and men were highly trained, had given them a moral authority that was

generally accepted. During civic and political fights, naval officers always appeared as

moderators or impartial judges whose decisions were almost universally accepted.

Only once, at the request of Congress, had the commander of the squadron rebelled

against the President, that is the Civil War of 1891. When the war ended, Admiral Jorge

Montt was elected president; and when he later returned to the Navy, he refused to

participate in political activities of any sort.

During the parliamentary regime which followed the Civil War, the country was forced to

live in almost constant political upheaval. Political parties multiplied, cabinets changed

constantly, but the Navy remained unaltered so that its officers could keep a solid

reputation as men whom the citizens could trust. However, in 1924 a bill was presented in

Congress to increase the pay of senators and deputies. Passage of the proposed bill was

considered an insult to the Armed Forces because their salaries were being effectively

reduced every day by the deteriorating economic situation. Several politicians took

advantage of the unhappy climate created among the officers and tried to attract the

commanders of the Santiago and Valparaíso garrisons. When they contacted Admiral

Guillermo Soublette, he refused to listen to them, but after talking to the President of

the Republic, Arturo Alessandri, he decided to join the conspirators and establish some

contacts in the Navy.

On 5 september 1924 a "Junta Militar y Naval" presented President Arturo

Alessandri with a list of petitions. This Junta was formed by 33 Army officers and only

four Navy captains, although Admirals Soublette and Luis Gomez Carreño had been involved

with another group called TEA whose designated purpose was to force Alessandri to resign.

The President demanded that the Junta be dissolved, and when the officers refused, he

resigned leaving the Vice-President as Chief Executive. When the Vice-President resigned,

a Junta de Gobierno was installed in which the Commander in Chief of the Navy, Admiral

Francisco Neff, was a member.

Since the desires of the original conspirators were not satisfied, a new Junta took

over on January 23, 1925 and detained Admiral Neff and his Minister of Marine, Admiral

Luis Gomez Carreño. The reaction of the Navy in Valparaíso was swift. A meeting of all

the officers in Valparaíso was called and the Navy issued a proclamation stating that it

did not approve of the procedures in Santiago nor of the political aims of the movement.

The Santiago Junta attempted to contact the Valparaíso regiments but their officers

decided to side with the Navy. In fact, a cavalry regiment, the "Coraceros",

boarded the squadron which was at anchor at Valparaíso, ready for any emergency. Tension

ran high and many observers thought a civil war would erupt. But the Santiago Junta agreed

to the Navy demands and a new Junta was formed with Admiral Carlos Ward as one of its

members.

Once the nation returned to political normalcy, the Navy did not get mixed up in

governmental affairs. When political movements and bloodless coups d'etat forced

government changes in Santiago, the Navy limited its activities to maintaining public

order in the ports.

In the years that followed the Navy was ready to support and assist the government when

its services were required. In 1927 President Carlos Ibañez appointed several Navy

officers to government posts and Captain Carlos Froedden even served as Minister of the

Interior. But as an American historian has pointed out: "(the Navy) still acted

within an institutionl framework, and, more significant, its chain of command, as well as

its discipline, remained intact."(11)

President Gabriel Gonzáes appointed Admiral Inmanuel Holger as Minister of the

Interior and other Navy officers served in civilian posts of the administration. The

election of Carlos Ibañez to a second term in 1952 placed many Navy officers in difficult

positions. Ibañez disregarded Navy traditions and forced the retirement of several senior

officers who had not shown political support for him. The Navy, however, remained loyal to

the President and the Constitution.

But the hardest test came with the Marxist regime which took over in 1970. Contrary to

what has been written, not only the Navy, but the Armed Forces of Chile, respected the

Constitution and the laws and actively cooperated with the Marxist government.

The first friction with the Navy occurred when the government tried to distract public

attention from the assasination of a former minister by altering Navy photographs in an

attempt to show contraband. The lower echelon officers who were aware of this

falsification were incensed, but somehow the whole affair was smoothed over. Moreover, the

President and the Marxist parties changed their attitude towards the Armed Forces. A bill

was sent to the Senate asking for a 49% increase in pay and the Navy was authorized to

purchase two Leander class frigates from English shipyards, as well as two Oberon class

submarines and the cruiser Gota Lejon from Sweden.

Admiral Raul Montero, Commander-In-Chief, was invited to visit the Soviet Union, but in

spite of a cordial atmosphere and the friendly relations established no material results

were produced. In the words of the Admiral: "The Soviets have nothing to offer. Their

strict discipline is in itself a contradiction to the system they pretend to enjoy".

The economy deteriorated badly during the second year of Marxist government and the

situation culminated in the trucker's strike of November 1972 which virtually paralyzed

the country. The political opposition would have liked nothing better than that the Armed

Forces to interfere, especially after the government parties sent mobs rampaging downtown

in Santiago and Valparaíso. The Armed Forces high command felt they should not interfere.

Navy intelligence was aware that a secret Marxist memorandum listed Admirals and senior

captains to be eliminated. Heading this list was Vice-Admiral José T. Merino, second in

seniority to Montero. While the political police kept a good eye on senior officers,

captains and colonels were able to file reports and take the political pulse of the

country. In October 1972 the secret monthly memorandum to the General Staff of National

Defense, stated:

While the civilians have complete liberty to pursue their roles, the military is

serving as a cushion between two antagonistic forces without getting any benefits and at

great sacrifices. They watch the country deteriorate, day after day, without being able to

participate in any decision... this can only mean that the armed forces are about to reach

the limit of obedience to their Constitutional obligation, and could, at any given moment,

be forced to take an unconstitutional stand.(12)

Two unrelated appointments in the Armed Forces were to bring two men into key

positions. The first was the appointment of General Augusto Pinochet to Chief of Staff of

the Army: the second, Admiral Patricio Carvajal to head of the General Staff for National

Defense. This committee was directly responsible to the three commanders-in-chiefs.

Carvajal proceeded to re-organize the emergency commands that Chileans have learned to

keep ready in the case of a national emergency, such as an earthquake, tidal wave, or an

internal revolt. The plan divides the country into differente commands, one for each Army

division and two Navy commands, one at Talcahuano at the other at Valparaíso. An Air

Command could be set up in Puerto Montt. It must be emphasized that these commands were to

act independently and immediately in case of emergencies, and all armed forces whithin

their area came under their authority, including the para-military police force, the

Carabineros.

The trucker's strike forced the government to call on the military. This move was not

without precedent. Almost all Chilean Presidents since the time of Balmaceda had relied,

at one time or another, on the military. On November 2, 1972 a new cabinet was sworn and

Rear Admiral Ismael Huerta took over the largest ministry: Public Works. The military,

headed by General Carlos Prats of the Army, settled the strike after he promised to end

the truckers supply problems. It is interesting to note that a word from the military was

enough to satisfy the truckers.

In a few months however, disillusionment set in. The Army became suspicious of its man

in the government. Admiral Huerta was uncomfortable in his post but felt that his

patriotic duty was to do everything possible to support the government. His capabilities

as an engineer and administrator were wasted because of his inability to get his orders

obeyed. Day after day, his Undersecretary presented him with documents to be signed and

more than once Admiral Huerta found illegal orders and decrees slipped in among the

documents to be signed. When the government announced food rationing without consulting

him, he demanded to see General Prats. Unable to get a satisfactory answer, feeling

cheated, a puppet in a government with which he did not agree philosophically, Huerta

presented his resignation. It was the President's first trouble with the Navy. Admiral

Montero did not want to pull the Navy out of the government. He attempted to find a

replacement, but Admiral after Admiral turned him down. Finally he ordered Rear Admiral

Daniel Arellano, who had spent most of his career at sea and who had just returned from

the United States and who no doubt knew little of the internal situation, to take over the

Public Works Ministry.

Huerta, back in the Navy, reported on the internal conditions of the government to the

senior officers, and went back to his regular duties. His detailed exposition of the near

anarchy that reigned inside Chile's largest ministry deeply concerned the Navy.

The Armed Forces remained in the government until the scheduled Congressional elections

were held. Although military authorities guaranteed that law and order prevailed on

election day, the military could not prevent a fraud of enormous proportions which gave

the Unidad Popular a small victory at the polls.

Right after the aborted attempt of the Second Armored Regiment to stage a revolt on

June 29th, 1973, the senior officers set up a fifteen man committee, five general officers

from each of the services. After several meetings the generals agreed that the government

must be presented with a memorandum containing a bill of particulars or list of demands.

After all, the June revolt had been put down thanks to the loyalty of the Armed Forces,

whose commanders did not agree with the politics of the government but still obeyed it.

The memorandum contained 29 points and it was agreed that the three Commanders-in-Chief

would present it to the President in person. But when Admiral Montero and General Ruiz of

the Air Force went to La Moneda, they found that Prats had already presented the

unfinished memorandum. They felt betrayed but said nothing. Admiral Montero was willing to

go along with Prats, but the Navy as a body was unwilling to compromise. Admiral Merino

refused to accept Montero's explanation, and together with the Commandant of the Marines,

Admiral Huidobro demanded that Montero resign. A meeting with the President himself could

not solve the impasse.

On August 9, 1973 a conspiracy was discovered in the Navy. Although the plot was almost

immediately detected, it produced a serious effect on the general public. New strikes,

public disorders, anarchy, and chaos reigned in the capital. It was time again to call on

the military and a Cabinet of National Security was sworn in on August 9, 1973. Admiral

Montero became Minister of Finance, a post for which he had no previous preparation

whatsoever. The new Cabinet was unable to bring about the same results that the military

had achieved in November of 1972. Congress passed a resolution calling on the Armed Forces

to resign from the Cabinet. General Prats resigned and General Augusto Pinochet was

appointed Commander of the Army. In the Navy, Montero managed to hang on. The Marxists

were specially fearful of the Marines, who had resisted all attempts at infiltration from

the Left. Merino was known to have right-wing tendencies and although Montero enjoyed the

full support of the President the tension and the pressure mounted.

On August 24, Montero finally resigned his post in the ministry but accordance to the

President's wishes he returned to his post as Commander of the Navy. The Admirals resisted

all attempts to be appointed to the cabinet and demanded that Montero resign his Navy

commission. Finally, Admiral Arellano, who had already saved the situation six months

before, agreed to take over the Ministry of Finance.

Still, it was in the Navy that tension reached the boiling point. The investigation of

the conspiracy showed that Senator Carlos Altamirano, a leader of the Socialist Party, was

the head of the plot. The Navy demanded that he be turned over to be tried. The government

refused. The Admirals demanded en masse that Montero resign and he finally agreed. Merino

was called from Valparaíso and arrived by helicopter at the Presidential Palace, La

Moneda. But the President demanded that the Navy drop the charges against Altamirano if he

was to be confirmed as head of the Navy. After six hours no agreement could be reached.

Merino returned to Valparaíso and that same night decided that action must be taken and

called for a meeting of general officers. He knew that the Air Force and the Army were

ready to act, but didn't know when. Each service had developed its own plan of action and

no coordination had been agreed upon. He ordered Admiral Huidobro to Santiago with a slip

of paper. It read:

Gustavo and Augusto: On my word of honor, D-day is the 11th and H-hour is 0600. If

you cannot take part in this phase with all the forces you command in Santiago, explain on

the other side. Admiral Huidobro is authorized to bring and discuss any topic with you. I

greet you in the hope of understanding.

And a postscript:

Gustavo this is the last chance. J.T.

Augusto: If you can't commit your full force from the outset, we will not live to

see the future. Pepe.1(13)

General Pinochet, in his own Memoirs, states:

The brief lines sent by the Chief of the I Naval Zone were transcendental. If the

Army had not been ready to act on the 14th I believe that the action would have failed...

I realized that I had no choice but to accept the Navy's request and move up the action

from 14 september to the 11th because in doing so we would avoid the imminent danger of a

civil war. 1(14)

On the morning of September 10th the squadron, composed of the cruiser Prat,

destroyers Cochrane, Blanco Encalada and Orella, the

oiler Araucano and submarine Simpson, plus two Navy

tugs, left port to join up with an American Task Force off the coast of Chile. The purpose

was to participate in the annual UNITAS operation, an anti-submarine warfare training

exercise held every year by the two navies. At midnight some of the 3000 men crew noticed

that course had been changed and the ships were heading back to port. Each captain had

been given sealed orders to be opened at midnight. At 0500 the crews were awakened by a

call to General Quarters and then an announcement was made through the public address

system: the Armed Forces of Chile have united in a movement to overthrow the Marxist

government. The men responded with enthusiasm.

The US Navy UNITAS fleet of four ships was just outside Chilean territorial waters.

Although it was still three full days steaming from the nearest Chilean port, an urgent

message was sent by the US Navy mission in Chile asking to refrain from entering Chilean

waters. The ships turned around and steamed to their next destination, Argentina, via the

Panama Canal; a detour of 9000 miles.

That afternoon a Military Junta was installed and Admiral José Toribio Merino was

sworn in as one of its four members. The Admiral believed that he acted in behalf of law,

order, and internal peace.

Since 1973 Chilean Navy actively participated in the task of national reconstruction.

Navy officers occupied, at one time or another, practically every Ministry in the Cabinet,

represented their country abroad, presided over government corporations, served as

governors, mayors, and administrators of public utility companies. But they remained,

primarily and above all, officers in the Chilean Navy. No member of the Armed Forces of

Chile received any pay other than his regular Armed Forces salary.

After the plesbicite and election which returned Chile to full democractic government

in 1989, Admiral Merino resigned as Commander in Chief and retired to a quiet life. He

refused to publish his memories and remained outside political life. He died in 1997. The

new Commander in Chief, Admiral Jorge Martínez pledged his support and the navy's to the

civilian government presided by Patricio Aylwin. According to President Eduardo Frei, the

Armed Forces have been exemplary in their subordination to civilian power.

The Navy itself has continued its normal growth, increasing its assistance to

navigators and to the merchant marine. Its traditional role has not changed. Boundary

disputes with its neighbors have place great demands upon the Chilean Navy. The long

distances between the nation's northern and southern territories plus the long standing

naval tradition has sharpenned the abilities of the men in maintnance, training and

general seamanship to the point where the Chilean Navy is considered "one of the

finest small navies in the world."1(15)

6 Mason, Theodore, B.M.The War on the Pacific

Coast of South America, Washington: Government Printing Press, 1883, p. 34. The

author owns a copy of this book previously owned by Luis Uribe who changed only one word

in Mason's translation of Prat's well known speech. "Children" was changed to

"My boys".

7 Mason, op. cit. p. 31

8 Grau, Miguel, Diario a Bordo del

Hu&laacutecar, Buenos Aires: Aguirre, p. 138

9 Typewritten notes and instructions found in the

Presidential Palace, La Moneda, in September of 1973.

10 The author was privileged to participate in part of a

training cruise and had a chance to observe first hand, the rigorous exercises which

included, small boat handling in the open seas for a full day, on short rations; climbing

the rigging to the top of the mast in the early morning; plus lectures on nautical as as

well as academic subjects.

11 Sater, William F. "The Abortive Kronstadt: The Chilean Naval Mutiny

of 1931" Hispanic American Historical Review, 60(2), 1980. pp. 239-268

12 Quoted in, López, Carlos, Allende and the Military,

Washington: CIS, p.8

13 See, Whalen, James, Allende: Death of a Marxist Dream,

Westport: Arlington House, 1981, p. 24

14 Pinochet, Augusto, El Dia Decisivo, Santiago: Andres

Bello, 1980, p.121

15 Robert Scheina, "The Chilean Navy", U.S. Naval

Institute Proceedings, March, 1988, p. 32

<< 4: Civil War || Bibliography